A Walk through Fashionable Tokyo

by Rick Kennedy

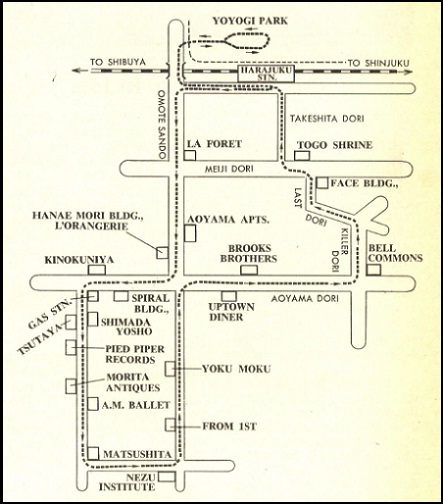

This walk, which begins with a promenade down Omotesando, the tree-lined boulevard which those with a romantic turn of mind like to think of as Tokyo’s Champs Elysees, is best undertaken on a Sunday. The only preparation necessary is the slipping on of some comfortable walking shoes and, if possible, the making of a reservation for Sunday brunch at L’Orangerie, about which more later. The walk might take between four and five hours, leaving plenty of time to get sidetracked.Take the Yamanote Line to Harajuku Station and exit this half-timbered ramshackle of a landmark by the Omotesando Exit, the exit nearest Shibuya. If you can manage to leave the station by 10:30, your timing for brunch will be pittari (“bang on the nose.”)

If the day is clear, you might like to see if you can spot Mt. Fuji from the span of the pedestrian bridge, but if not, stay on the side of the boulevard nearest the station for now. (On Sundays, the whole boulevard turns into a pedestrian mall from 1 to 5 o’clock.)

Head down Omotesando. The trees are keyaki—Japanese elm. Thirty years ago this was a sedate part of town, but as you can see it has been heavily infiltrated by a ragged commercialism: street peddlers of jewelry who find the generous sidewalks accommodating, purveyors of gelati and pasta, sidewalk cafes, hair-dressing establishments, chocolatiers and pizza and hamburger factories. Young Tokyo is learning a new code of etiquette which sanctions the licking of an ice-cream cone while strolling.

Cross Meiji Dori, one of the city’s major arteries, and head up the gentle slope. Fashion houses are on the back streets all around you.

The brooding block of apartments all overcome with ivy and clinging vines which stretches to the top of the slope on this side of the street, is the Aoyama Apartments. Tokyo’s first stab at a new way of living in cities, the apartments were built in 1925 with a loan from a forward-looking Imperial princess. They are standing on extremely valuable real estate and, although they are now gently crumbling away, it seems to be practically impossible to get all 150 tenants to agree to sell at the same time so the apartments could be torn down and new ones put up. Nevertheless, the apartments are slowly being taken over by boutiques who like to install great plate-glass windows: the effect is similar to that of neon signs in a castle.

Cross the street and window shop at Paul Stuart, clothes for the discreet dandy, Gallerie de Pop with its flamboyant flower arrangement in the window, Shu Uemura, the high priest of make-up, the Cocoon Building and Chez Toi (“La mode s’inspire de l’epoque. Nous vous offrons une grande variete de creations qui vivent avec votre epoque” is inscripted in florid script on the door.)

Brunch runs from 11 a.m. to 2:30 p.m. at L’Orangerie in the Hanae Mori Building. (You will have called M. Nozawa, the maitre d‘, at 407-7461 early in the week to tell him you are coming.) If you disdain the elevator and take the escalator to the fifth floor, you will wind up through a display of the current Hanae Mori collection — great blasts of haute-couture color, with shop attendants all in black. Here the wife of Mitsubishi France comes to buy the evening dress she will wear to the opening of the Paris Opera. It might cost $3,000, and be constructed of thousands of iridescent sequins all sewn by hand.

L’Orangerie is one of Tokyo’s finest French restaurants and was inspired by L’Orangerie in Paris, one of Madame Mori’s favorite places. Here the idea of brunch was introduced to Tokyo and it is here you will still find the most elegant brunch in the city. It is served buffet style, but your” reservation gives you your own table, which is immaculately set, as if brunch were the premier meal of the day. It is an eclectic spread, running from stuffed tomatoes to sushi, from cheeses to bagels, as well as more standard fare. The tariff is ¥3,000, and a bottle of Moet and Chandon is ¥12,000.

Now well-brunched, let us move on.

In the basement of the Hanae Mori Building is a collection of antique shops, a fine place to browse for a bit to let brunch settle, Ao sells antique indigo fabrics. Idee sells articles of “interieur retro,” such as articles for the dressing table. Soul Trip sells baubles Proust might have kept on his bedside table. Old telephones and typewriters, lace chemises and teddy bears, monocles and signet rings, fountain pens and art-deco evening bags, Laligue glass and cameo brooches, all studiously arranged. How about a 1900 Vacheron Constants gold repeater pocket watch for ¥800,000. But enough!

Cross Aoyama Dori (known to motorists as Route 246) and turn left. The Spiral Building, a fine example of the New Tokyo Architecture which is beginning to make itself felt in New York and Los Angeles, too, presents itself as for inspection. The building is worth a stroll-through. Walk in and go around the atrium to the right all the way to the rear of the building. There is sure to be an exhibit there which breaks some sort of new ground. Mount the great spiral staircase in the back and come out on the second floor, where a dozen very large tables are spread with classy quotidian objects: tools and soaps and glasses and ribbons—here you can buy a souvenir of the New Japan Design.

Now out in the street again, to continue down Aoyama Dori. Turn left at the gas station across from Kinokuniya, which is to Tokyo as Fauchon is to Paris. This street is informally called Koten Dori, “The Street of Antique Shops.”

Just around the corner is Shimada Yoshio, a bookstore devoted to coffee-table books on motor cars, aircraft, gardens, graphic arts, cuisine and architecture. Other shops along Koten Dori are Tsutaya, which sells all manner of implements for flower arranging, the tea ceremony and kohdo, the ancient art of incense appreciation; Pied Piper Records, a tiny place jammed to the rafters with foreign records, many of them impossibly arcane, and Morita Antiques, which specializes in antique textiles and folk art. The street is heavily stocked with ultra-spare boutiques like Kenzo, where no piece of furniture would ever dare to intrude. You will see elegant dogs on leashes and highly polished foreign motor cars of unusual provenance.

This being Tokyo, you will also come across the occasional terribly battered wooden ceilling with a tin roof and cracked window panes. Up ahead on Koten Dori is one of the most famous of these relics, which nestles up against a swank, marble-halled apartment building, sporting a sign that says “I will never sell!”

If this anomaly does not engage your curiosity, turn off the left at Matsushita Associates, Original Ukiyoe Prints, which is, however, closed on Sundays.

This street too is closed to automobiles on Sunday. At the end of the long wall running along the right-hand side of the street, turn the corner to the right and you will see the entrance to the Nezu Institute of Fine Arts (closed Mondays and the month of August). It costs nothing to walk in the wonderfully landscaped garden with its two teahouses, carp lazing in deep pools, groves of bamboo and thick carpets of moss. It is miraculously quiet in the garden, save for the sound of trickling water, and the pace of your walk will slow to contemplation.

It costs ¥500 to enter the museum itself, which is famous for its collection of massive Chinese bronzes and ormolu clocks built in the style of Faberge Easter eggs for an emperor of the Ching Dynasty.

Now head back down Aoyama Dori. You’ll pass the From 1st Building, one of Tokyo’s first buildings to be devoted solely to fashion, and Yoku Moku, whose courtyard is a favorite spot for cappuccino and a wedge of pastry.

At Aoyama Dori, turn right. You’ll pass Uptown Diner, a prime example of Tokyo’s continuing love affair with the American ’40s and ’50s. It serves hamburgers, chili and Reuben sandwiches assembled by a French chef and the booths are carefully set with bottles of Heinz ketchup and French’s mustard. Young men in generously cut jackets and long-skirted ladies in black and white eager to try everything in the world at least once come here to sample the delicacies of the New World.

Across the street is Brooks Brothers, with its racks of brass-buttoned blazers and piles of cashmere pullovers. They’re doing very well in Japan and have stores in Osaka and Sapporo.

A hundred meters beyond the solemn aisles of Brooks Brothers, turn left onto “Killer Dori.” (There are many stories of how the street got its name, but nobody really knows, as the name is unofficial.) This is yet another fashion street—with boutiques called Barbiche, George Sand, Nicole and Peyton Place. On Sundays specializes in art books and museum-quality postcards, some of photographs of old Japan.

At a little faux-bucolic shop called Afternoon, which sells hand-crafted sweaters, turn left onto Last Road (“Lasto Rodo” in Japanese.) Here, there are still more boutiques: K-Factory, Yestermorrow, Kid Blue Muse, Vazarely and Zaftig.

On the right, just as Last Road runs into Meiji Dori, is the Face Building, another example of New Tokyo Architecture. Take a left here onto Meiji Dori.

On the first and fourth Sunday of each month, a flea market is held on the grounds of Togo Shrine. There are hundreds of old silk kimono for ¥1,000 each, old leather suitcases with labels from around the world, trays of military buttons, antique pressed-tin advertisements, old toys and musical instruments— it’s one of the city’s best flea markets.

By now, all but the athletes among us will be beginning to wilt. We are now almost back to home base, Harajuku Station, but first we must traverse an obstacle course called Takeshita Dori. Continue down Meiji Dori until you see a building sporting a sign which says “Marron,” and turn right there.

Takeshita Dori is 200 meters long and jam-packed with teenagers from all over the country who come here to rig themselves out in frilly socks, lace collars, sunglasses and striped tights—or whatever the extremely evanescent fashion of the moment may be—and to eat crepes and have their hair cut the way the teen magazines suggest. It’s going to take you 20 minutes to make your way up this short street, through all the massed humanity, but this is somehow triple-distilled Tokyo and too much a part of this crazy city to miss.

At the end of Takeshita Dori is the lower exit of Harajuku Station. I’ll certainly understand if you decide to call it quits at this point, but just ahead lies another classic Tokyo scene. Yoyogi Park just up the hill to the right is a sanctifed spot for street performers. It’s a long-playing piece of theater, and the underlying motif is ’50s punk.

The Tokyo Rockabilly Club, whose members all wear scuffy pointy black shoes and sport enormous overhanging pompadours, dance to the music of Bill Halley and the Comets. The young ladies, who dance by themselves, wear crinolines and saddle shoes. The whole thing is just too much…