One of Japan’s most renowned living artists, Hiroshi Senju is based in New York but often spends time in Japan. He’s known globally for his famous waterfall paintings using the traditional Nihonga painting style.

Born in Tokyo in 1958, Senju graduated from Tokyo University of Arts in 1987. Ten years later, at the 46th Venice Biennale, he became the first Asian artist to receive an Honorable Mention Award. He was then the president of Kyoto University of Art and Design from 2007 to 2013 and is presently a professor at the university’s graduate school.

Senju recently came to Tokyo to receive the 77th Imperial Prize and the Japan Art Academy Prize for his achievements in creating outstanding works of art and for his contribution to the advancement of arts. We had the chance to speak to him during his stay.

Hiroshi Senju in his Tokyo home. Photo by author.

1. What impact has the pandemic had on your life and your creativity?

What I feel strongly about this pandemic is that the next era arrived very quickly. We’re witnessing the transfer into an era of artificial intelligence and the presence of technology in our daily routines, in everything we do. On the other side, we had more time to think about the importance of human existence.

Through history we’ve learned that the role of the artist is to point out what’s missing and to express what’s important. Take as an example the Black Death, which almost wiped out half of Europe in the 14th century. After this period came the Renaissance where Michelangelo admired the health of the human body, while (Leonardo) Da Vinci turned to the sciences. In the history of humans, we had many diseases, world wars and civil wars. The role of art was to help or to offer a way out of darkness.

Regarding myself, I have to say that, during the pandemic, I was trying to paint as closely to how I was before the coronavirus spread. At the same time, keeping my lifestyle as healthy as possible and framing my creativity in the context of the time. And so, I found myself paradoxically more energetic during this last period and this energy reflects in my work too.

In this digital world, we use only our two senses – the eyes and ears. I could use 3D technology to organize an online exhibition but what about the smell, the texture, the temperature? These are all important things for a truthful human experience — to feel and to live with all senses.

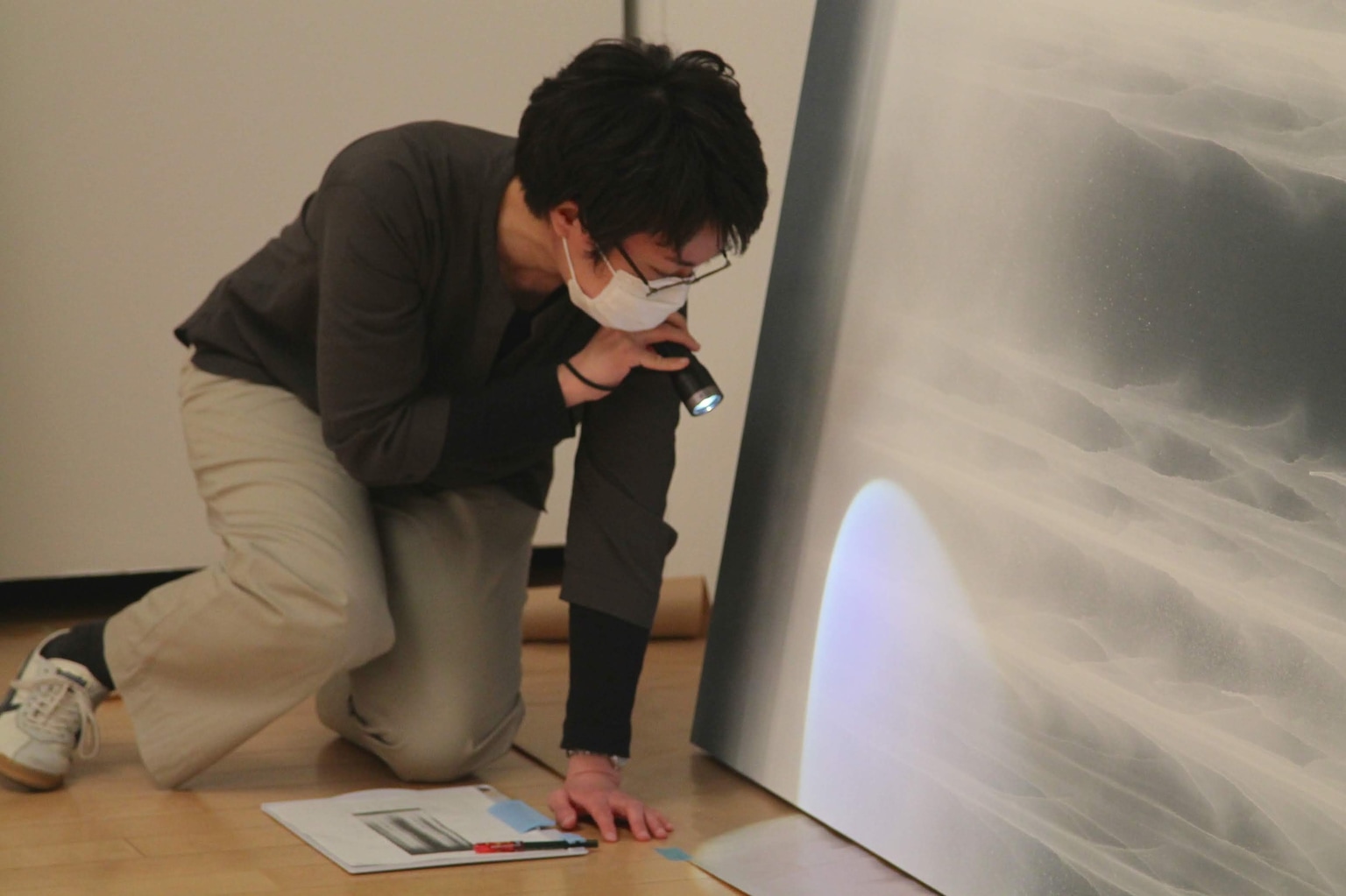

Staff member while preparing a Hiroshi Senju exhibition in Kita Kyushu in 2019

2. Do you have any secret spots in Tokyo where you like to spend time?

I don’t think there are any secrets left in the age of social media. For me personally, it’s the early morning visit to Meiji Jingu. The sunrise at 5 am, the shy light coming through the centenarian trees around the temple, the singing of the birds and then watching the monks as they worship. That’s my peaceful and slightly mystical routine when I’m in Tokyo. The fact that inside one of the biggest and busiest cities in the world you have this enchanting scenery is simply magnificent.

3. Can you tell us about the transformation of Tokyo’s urban landscape during and after the 1964 Olympics?

Being born in 1958, my childhood is tied to a city where you could still feel the consequences of the devastating events from the war. At the same time while sensing a very high level of development that could especially be felt in the framework of the 1964 Olympics. That year I was starting school and I remember the walks with my mom, not only around Yoyogi where the new Olympic stadium was flourishing but also our walks around Ginza and Roppongi.

A stamp printed in Japan shows Komazawa Gymnasium, a venue for the 1964 Olympics in Tokyo

Tokyo changed dramatically. My way of observing and experiencing Tokyo changed too. The time has changed and that’s why some familiar things seem to be different. Take as an example Tokyo Tower, which at the time was built to be a symbol of high technology. Today, it’s more of a retro symbol. As time flows, my feelings about some Tokyo symbols, whether they are modern or traditional are changing. Asakusa’s Sensoji is one of those places. I remember it from my childhood and even though everything remained the same in the material sense, the atmosphere is completely different. The area around Asakusa is still beautiful and unique, but it lost some of its local meaning and became a tourist spot. The locals adapted their life to that.

However, despite all of this, I love Tokyo. We have incredible architecture in the city today. Japan has more Pritzker Prize winners than any other country and most of them were or are living in Tokyo.

4. When and why did you move to New York?

I left for New York shortly after receiving the prize in Venice. After World War II, it took over Paris as the world center of art. Especially after the 1960s and until nowadays, New York became the most important place on the world art map. At that time the exchange of information was slow and I wanted to be at the center of the events. With the Internet and all social media, the situation is now different. I believe that if you’re a good artist today you can be based anywhere.

5. How can one become a successful artist?

Each artist is special. In art there is no model or formula for how to become a successful, famous and respected artist. I believe that what helped me personally was the fact that in New York I was the only artist who was painting with old techniques, using exclusively natural pigments obtained from minerals, corals and shells. This technique of painting is more than a thousand years old and I do it in a traditional way. I also use old Japanese paper and animal glue.

Thousands of years ago we weren’t divided between East and West. It was one world, nature, the animals and us, the humans. I wanted to keep the technique which existed before all those revolutions, as I wanted to create art everyone could relate to. My expression comes from our common feelings, our common memories, our common instincts, our common beauty whenever and wherever we are. I believe that these are the little things that brought me to where I am today. Luckily, there are now many artists who want to enter the depth of human existence and that’s a valuable artistic trait.

“Waterfall” by Hiroshi Senju in Grand Hyatt Tokyo.

Photo by Alma Reyes

6. Do you believe that having more artists connected can bring some positive changes?

Even though it looks that today we are connected more than ever, I think that the internet is just a partial tool. We need time for everything we do. Maybe we are more connected, but we are not together. People virtually build relationships, play virtual games and make virtual revolutions. And when they get bored of all that they literally delete it all. And that’s not good.

For artists, I think the internet was a real struggle at the beginning. Japanese movie director Takeshi Kitano described this struggle best. He was beating himself until he felt pain, swelling and tears. He simply wanted to go through this physical experience because everything became virtual.

On the other hand, the internet, with virtual exhibitions for example, allows us to reach an audience we would otherwise never have access to. But then, I still think that art should be a way to bring people outside of their homes and connect around something more tangible than the virtual. Again, in-person communication and interactions are not only about the words but the sensations and the atmosphere. So, our common goal is to create a space for authentic communication and dialogue through art.

7. In bringing common experiences to people, would you say that we can change the way we perceive others and culture?

We’re living in a world that is filled with unique and diverse cultures. But at the same time, we’re all human beings and belong to the same species. Art gives us these two different messages. Sushi and Japanese paintings are Japanese culture while pizza and Michelangelo are from Italian culture, but both can be enjoyed as our heritage, as ours. If we observe humanity from that point, if we can act that way, I think we can achieve peace.

8. What’s your starting point when creating?

Inspiration comes from daily life, not from a moment. It’s the accumulation of daily life — happiness, sadness, regrets and everything else — that gives me creativity. It comes from every moment and every daily routine.

View this post on Instagram

9. Your brother’s a famous composer and your sister a famous violinist. Were your parents also artists?

No, my father was an economist, my mom was a homemaker and my grandfather was a scientist. Of course, it was hard to convince our parents that we wanted to make art. At the end of the day, art is about communication and the three of us had to explain to our parents what art meant to us. We had to teach them to understand art and that’s how our parents became our first audience.

I believe that the success of becoming what you want to be is guaranteed if you’re able to make your parents understand why that is so. And if you succeed in that, then you’ll be successful with your choice. At first, I wanted to be an architect, but then, by chance, I came in contact with natural pigments and that was the starting point of my career.

10. We’re now into the era of Reiwa. What does that word mean to you?

Reiwa means the statement of beautiful harmony. However, we had a lot of natural disasters and now a pandemic. I feel more than ever we need to strive to achieve that statement. To achieve real beautiful harmony, we need to work together. That’s the message from the Reiwa era.

All photos by author, unless indicated otherwise.

More interviews: