The Problem in Numbers

Every year in Japan more than 80,000 people are welcomed in to new homes—it’s a country second only to America in terms of its adoption rate—yet when it comes to child adoption it’s lagging well behind the rest of the developed world. The vast majority of adoptees here are adults—particularly males in their 20s and 30s—often used as a tool to keep family businesses running if there is no biological heir or if the biological heir doesn’t seem like a suitable candidate to take over the company. At the same time tens of thousands of kids are still being brought up in institutions rather than a family-based setting.

“It’s an incredibly sad situation,” says Eriko Takahashi, Program Director of Disability and Social Welfare at Nippon Foundation. “I’ve visited some baby institutions and you can see the staff care a lot and really try their best, but just two or three adults with twenty babies: it is not right. Children should be living in a family environment, ideally with their biological parents; if that is impossible, then with relatives or foster parents. In Japan roughly 39,000 kids are in care right now; however, only around 300 adoptions are arranged through the child advisory services annually. Then there are about 100 through private bodies. It is nowhere near enough.

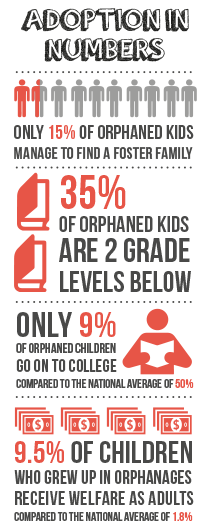

“It’s very unfortunate that most children in care here have to stay in institutions. Just 15% live with foster families—that is a much lower rate than other developed nations. In Australia it is more than 90%, in the UK and the US more than 70%. These countries realize the damage that institutionalization can cause kids, whereas in Japan people just aren’t aware. Speaking to local authority figures there is a general view that institutions are good for kids because they are taken care of in a safe environment; yet whilst this is true, it fails to take into account the psychological impact that these places can have.”

What Science Says

The most comprehensive study on the effects of institutionalization for children began in Romania at the start of this century. Ten years after the fall of the brutal Nicolae Ceausescu regime—an era when contraception and abortion were made illegal leading to thousands of kids being forced to grow up in overcrowded, understaffed state-run facilities—The Bucharest Early Intervention Project took a sample of 136 children and placed half of them in high-quality foster homes and kept the other half in institutional care.

The kids were assessed at 30, 42 and 54 months, then again at eight years in a variety of developmental domains including brain, behavior, cognition, language, social-emotional development, attachment and physical growth. The results showed that kids who had been institutionalized had significantly lower IQs (an average of 65 compared to 103), didn’t smile or laugh as much, were less likely to initiate or respond to social interaction and struggled to form healthy attachments with their caregivers.

Since the project began, thousands of kids in Romania and neighboring European countries have been moved into family-based solutions. There is still a long way to go; however, big efforts are being made to deinstitutionalize. The same cannot be said of Japan. A major stumbling block here is that biological parents retain legal custody of their son or daughter even if they have abandoned them. In such cases a child may be placed in temporary foster care, but is far more likely to end up in an overcrowded facility with little personal space.

A recent study by Human Rights Watch entitled “Without Dreams: Children in Alternative Care in Japan” revealed that sexual and physical abuse continues to take place in institutions; at the same time there are insufficient means to report these kind of problems. As part of the investigation they interviewed 32 kids in alternative care and 27 adults who had previously been in alternative care. Noted testimonies included a teenager who told them she had no dreams for the future, while another said he was often beaten by older kids when they were having a bad day, but as the only staff member was an old lady there was nothing anyone could do. One former resident in Ibaraki said that she was now “happy” working in the sex industry because “somebody, even though a stranger, actually listened (to her).”

The Dangers Of Institutionalization

Sophelia Lee—a popular blogger who has seen first-hand the kind of harm these kind of places can have on children—recently spoke to Weekender about her experiences volunteering at various institutions in Japan.

“It’s hard to put into words how profoundly damaging institutionalization is for children,” she says. “I often heard kids refer to themselves as ‘suterareta ko’ and ‘iranai ko’ (abandoned and worthless children). A lot of them have low self-esteem and seem depressed. Even the very young ones are clearly aware that they are missing ‘normal’ childhood experiences. Some of the games they initiated with me included ‘being dropped off at kindergarten by Mama’ and ‘riding on Mama’s bicycle in a baby seat.’ They’ll see little everyday interactions on TV and when they’re going to and from kindergarten or school, but have no direct experience of it themselves.

“For some kids the longest relationship they’ve had with a caregiver is two years. There’s just no chance to form any lasting emotional attachment, and a lot of them struggle with basic interpersonal skills like empathy and regulating their emotional state. In larger institutions every minute of every day is scheduled, the kids have no experience of independence or managing their own time. Some have never been inside a supermarket or seen basic food ingredients because they have simply eaten in a dining hall their entire lives. A woman interviewed for the HRW report mentions that when she was sent to live independently she didn’t even know how to switch on a light. They wait passively to be told what to do and how to do it, then one day they’re sent out into the world and expected to be able to find and keep work.”

“Even the very young ones are clearly aware that they are missing ‘normal’ childhood experiences. Some of the games they initiated with me included ‘being dropped off at kindergarten by Mama’ and ‘riding on Mama’s bicycle in a baby seat.’”

Life can be extremely difficult for former residents after they leave institutions. Many are forced to either accept low paid work or face up to a life of unemployment. According to a survey by the Tokyo Metropolitan Government around 9.5% of children who grew up in orphanages receive welfare from the state—that compares with a national average of 1.8%. The report also revealed that kids from institutions are far less likely to graduate from high school or go on to further education. Patrick Newell—co-founder of Tokyo International School and the man who brought the TEDx conference to Japan—is trying to change that. In 2006 he launched “Living Dreams,” an NGO aimed at enriching children through experiential learning.

What’s Being Done to Improve Adoption in Japan?

“It’s a bit silly really,” Newell tells Weekender. “You have this nation that desperately needs youth, yet more than 30,000 kids are stuck in the middle with a bleak view of their future. 35% of the children in institutions are academically two grade levels behind the rest of the country and only around 15% go to college. In order to get that level up they need more access to resources and technology. “Living Dreams” provides a one-to-one program with secure cloud based computing which we plan to take nationwide.”

Another organization attempting to ease the plight of abandoned youngsters in this country is The Nippon Foundation and its “Happy Yurikago (Japanese for cradle) Project.” Over the past couple of years they have provided financial aid for private adoption agencies, set up telephone and email advisory services for families that have adopted a child, and organize numerous seminars for couples considering adoption in Japan. They have also organized many study sessions for women worried about pregnancy so they know there are options available.

Groups like Human Rights Watch and The Nippon Foundation are helping to raise awareness about the kind of damage that institutional life is having on youngsters in this country. Both organizations continue to lobby the government demanding radical changes to current laws that continue to favor parents’ rights over the welfare of their children. These rights go against the UN guidelines for the Alternative Care of Children, adopted by the UN General Assembly in 2009, which states, “alternative care for young children, especially under the age of three, should be provided in family-based settings.” For so many kids in Japan this kind of setting is like a dream in a far away place; that is something that has to change.