Lieko Shiga, born in central Japan in the 1980s, has long felt discomfort with “the coziness and automation” of the modern world. Fifteen years ago, the Kimura Ihei Award-winner moved to Japan’s Tohoku region in the northeast of the country to document life in a Miyagi Prefecture village. Tragically, this community was devastated by the Great East Japan earthquake of March 2011 and Shiga, who lost her studio and much of her work, temporarily relocated to emergency housing. As one of the few leading artists to have directly experienced the tsunami, she centers her practice on engaging with locals and illuminating the complexities and hypocrisies of post-3.11 Japan. Her photography explores relationships between people and nature, themes of multigenerational memory and imagination’s role in considerations of life and death. Curator Mariko Takeuchi aptly described her as “a canary that sings in the darkness, but towards life.”

You said in a previous interview that one factor behind your move to Tohoku was a desire to “go right to the depths of historical and social contexts.” What did you have in mind then, and how has this played out?

I wanted to understand the social issues and history of the land I was photographing, out of pure curiosity. Because photographs are so easy to take, before simply shooting them it seemed crucial to learn what the scenery contained, what kinds of cause-and-effect relationships existed there. Through trial and error, I developed a process of “preparing to photograph” that, even after the disaster, remains very important to me. In fact, I feel I have become even more conscientious about it since.

Lieko Shiga, from Raisen Kaigan (2012)

Rasen Kaigan (Spiral Shore), your series presented at Sendai Mediatheque in 2012, seemed in some ways like an attempt to make a fresh start after 2011. Could you talk about how you managed to begin again after experiencing so much devastation?

I fled from the tsunami in my car with only my wallet and cell phone. I was left with almost nothing — even my camera was washed away. It was about a week before I could take photographs again (I borrowed a camera from a friend of a friend). The area where I lived had been reduced to rubble and I felt desperate to capture the rapidly changing landscape as the debris was cleared. Many people’s personal photographs were swept up and scattered by the waves, so together with friends I collected, cleaned and returned them to their owners. In that way, I resumed my photography only a week after the disaster and found myself busier than before.

Lieko Shiga: Human Spring, your show at Tokyo Photographic Art Museum in 2019, featured huge photographic prints. Could this tendency to do things on a larger-than-life scale be related to expressing vitality itself?

With photographs larger than the subject’s actual size, viewers start to see only details as they approach the image; they lose sight of the picture as a whole. Conversely, by physically distancing themselves, they can finally realize the entirety of what is shown. I wanted to use enlarged photographs to express that what we see changes depending on the position from which we view it.

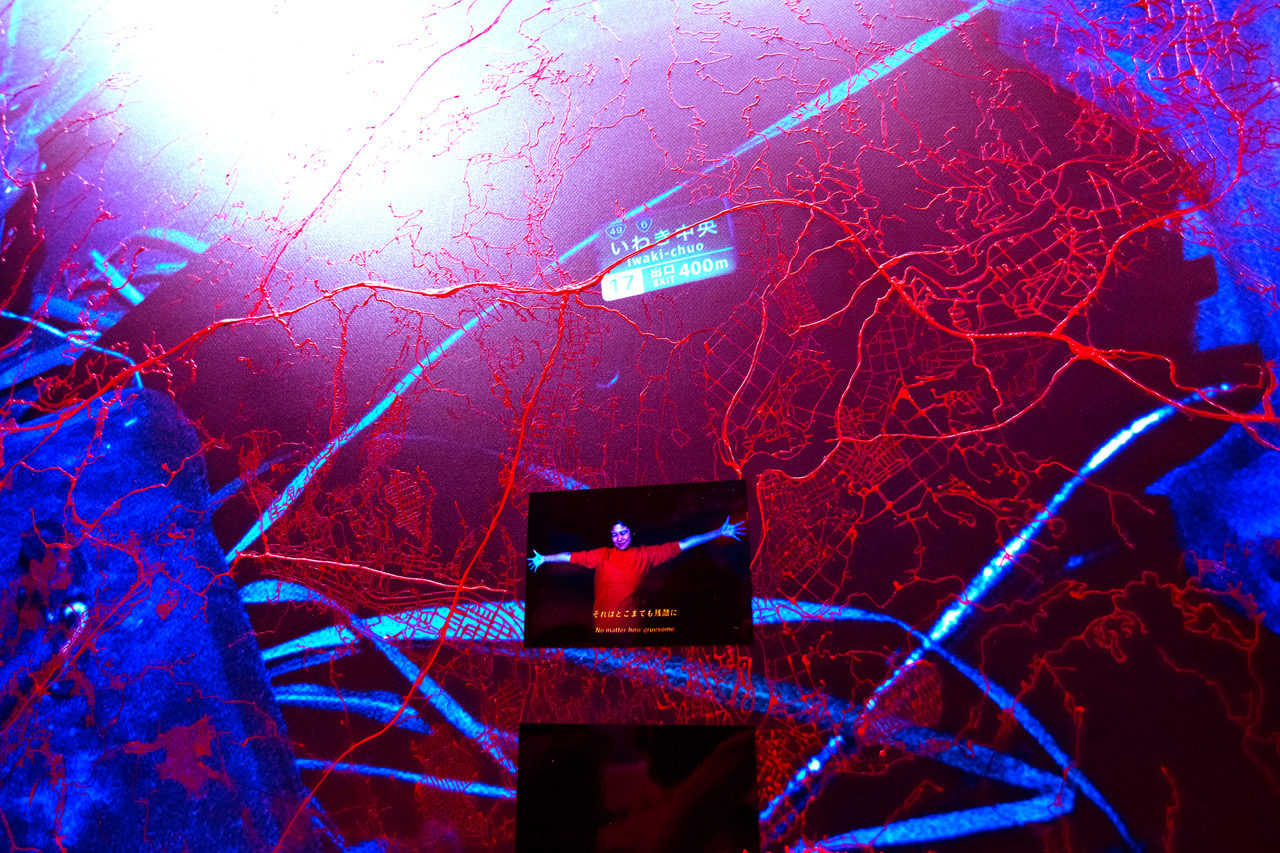

“Lieko Shiga: Human Spring” (installation view) at Tokyo Photographic Art Museum (2019)

The protagonist of Human Spring was said to embody nature through visceral reactions to the change of seasons, representing an “eternal present” — perhaps similar to a photograph. Was your aim to memorialize him, or to grant a kind of immortality through art?

It may have been a memorial, or something like a dedication. He made me realize the depth and profound importance of humanity’s relationship to nature, and I think I was trying to respond to this in my own way.

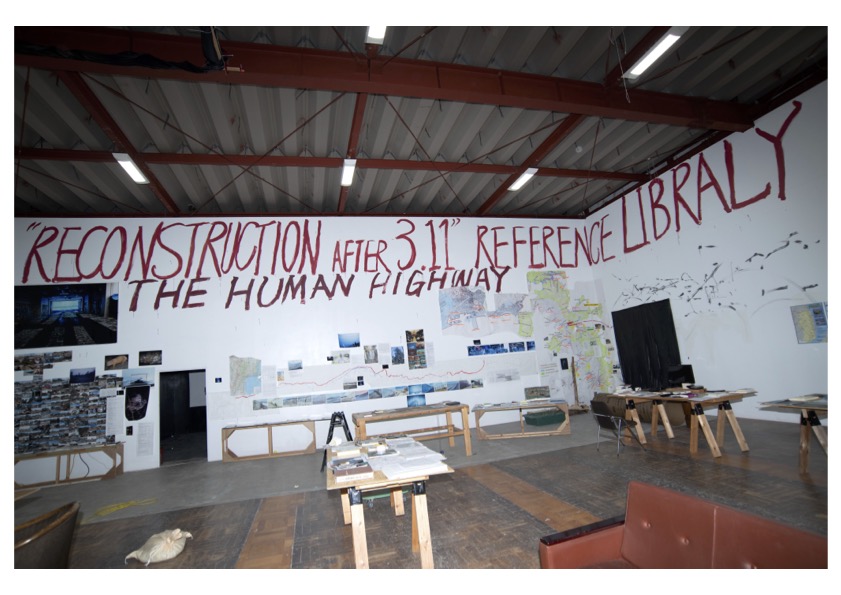

Waiting for the Wind, your Tokyo Contemporary Art Award exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo, describes the post-3.11 reconstruction of Tohoku as a “déjà vu of early modern Japan.” Could you elaborate on this?

The world that was swept away by the tsunami was an experience of what happens when modernity is destroyed, even for a moment. That night, death was laid bare before me — it was close enough to touch with my own hands. But even though I panicked with fear, the disillusionment I’d been harboring until then disappeared, and I vowed I would never forget what happened. What I’m trying to say is that when I saw the world rendered dysfunctional, I understood that what we call society is pieced together fumblingly — and sometimes badly — by human beings. It made me think about how alone I was in my ‘social’ existence. So, when I perceive the things I’ve studied about modern Japan in books and images since childhood being repeated in the process of post-disaster reconstruction, I call such moments ‘déjà vu.’

The cruelty and beauty of nature vs. the cruelty and beauty of humanity is a major theme in your work. While nature isn’t something humans can entirely control, they also often fail to restrain their own cruelty. What do you think is the role of art in this situation?

I think there is indeed a part of humanity that cannot restrain its cruelty. But if you look at humanity on a more individual level, you see there are people trying all kinds of ways to address cruelty and greed. Art is an interesting field, where you can pose unique theories of “What if…?” and actually test and perform them in your work. I think with enough of this trial-and-error approach, humanity as a whole would cease to run amok.

What has been your experience of working through the COVID-19 pandemic? Has it altered your creative philosophy or process?

It was difficult to go out, so if I had to, I tried to think carefully and act intentionally as I worked. What was invisible to the eye became a source of anxiety, and the situation revealed individual differences in what people found frightening. My work and process didn’t change much, but I did consider how nothing in the future is guaranteed and how the virus seemed like an allergic reaction to society by nature — one that will likely happen again before long.

Studio Parlor, the space you run in northern Miyagi, is a place where anyone can come to relax and simply exist. You’ve said you consider it “an answer to years of questioning.” How important are these kinds of “third-places,” which are neither entirely public or private, in today’s society?

Since people stay for long periods of time, it seemed key for the space to feel like nothing in particular: not a cafe, not a bookstore, not a gallery. To me, it’s like a ‘workplace with an open door.’ At times, I wonder whether my purpose there is to work or have people gather. Spending time together in the studio, our individual issues become communal. I think places where problems can be shared are necessary in our current age of information overload. Exhibitions are also important, but I now believe it’s even more vital to open up places of creativity.