When Patrick “Lafcadio” Hearn, a writer of Greek-Irish heritage, arrived in Japan, it was the height of the fin de siècle era; a time when the looming 20th century was presumed to signify a symbolic break from the past. In the West, art for art’s sake was all the rage, while the ideals of progress and respectability were making way for pessimism and degeneration.

Hearn, as with many of his literary contemporaries, was discontented with what he perceived as the failings of Western society. So, he looked to the East in search of hope. He was fond of Japonaiserie, East Asian aesthetics, and harbored romantic views of Japan as a quaint and picturesque utopia, unspoiled by the demonic forces of industrialization. It’s no surprise, then, that a short stint in New York, one of the “nervous centers of the world’s activity,” gave Hearn the impetus to emigrate.

“[New York] drives me crazy, or, if you prefer, crazier; and I have no peace of mind or rest of body till I get out of it. Nobody can find anybody, nothing seems to be anywhere, everything seems to be mathematics and geometry and enigmatics and riddles and confusion worse confounded,” he wrote to his friend, Joseph S. Tunison. “One has to live by intuition and move by steam. I think an earthquake might produce some improvement.”

The former residence of Lafcadio Hearn in Matsue, Shimane Prefecture

A New Start in Japan

William Patten, an art editor at Harper’s Magazine, offered Hearn a lifeline: the chance to move to Japan and write about his experiences for an American audience. Once Japan had opened its doors to the world at the beginning of the Meiji era (1868-1912), Western writers, scholars, missionaries and diplomats flooded in en masse. And on the face of it, Hearn was just another white man heading off to the Orient to give his life a renewed sense of meaning. But he was never one to travel by numbers. The trails he blazed were intellectual as much as physical.

“In attempting a book upon a country so well-trodden as Japan,” he wrote in a letter to Patten outlining his vision of the project, “I could not hope… to discover totally new things, but only to consider things in a totally new way… The studied aim would be to create, in the minds of readers, a vivid impression of living in Japan — not simply as an observer but as one taking part in the daily existence of the common people and thinking with their thoughts.”

It was a slightly naive objective; with whiffs of the Orientalists that he would later differentiate himself from. But it was based on reasoning. After arriving penniless in the United States in 1869, Hearn had traveled widely; to the dancehalls of emancipated slaves in Cincinnati, with Creoles in the bayous of New Orleans and to live with Caribbean islanders in Martinique. Cultural anthropology was, after all, his métier. Though upon reflection, Hearn admitted his naivete too.

“Long ago, the best and dearest Japanese friend I ever had said to me, a little before his death: ‘When you find, in four or five years more, that you cannot understand the Japanese at all, then you will begin to know something about them,’” he wrote in his final book, Japan: An Attempt at Interpretation.“After having realized the truth of my friend’s prediction — after having discovered that I cannot understand the Japanese at all — I feel better qualified to attempt this essay.”

Lafcadio Hearn

Hearn the Romantic

Hearn’s initial journey was a self-fulfilling prophecy: if one goes to Japan expecting to find the place of one’s dreams, the place of one’s dreams one often finds. Already in love with Japan when he boarded a steamship headed across the Pacific in the spring of 1890, he found his affections deepened the moment he caught sight of Mount Fuji from the deck of the Abyssinia. He then traveled ashore via a wooden sampan, stepped onto the port of Yokohama and began exploring a city of bluish tiled roofs, lattice-fronted shops housing curios of the most bewitching designs and lantern-framed walkways where passersby wore a style of clothing that he’d only ever seen in art exhibitions.

Hearn went to bed that night in a state of rapture. He felt “indescribably” towards Japan, as he wrote to his friend and confidant, Elizabeth Bisland.

“I love their gods, their customs, their dress, their bird-like quavering songs, their houses, their superstitions, their faults,” he continued. “And I believe that their art is as far in advance of our art as old Greek art was superior to that of the earliest European art-gropings — I think there is more art in a print by Hokusai or those who came after him than in a $10,000 painting— no, a $100,000 painting. We are the barbarians! I do not merely think these things: I am as sure of them as of death.”

This is what makes his development as a writer and thinker in Japan all the more interesting. His early years were defined by impressionistic essays on the country itself, regaling readers with the “tender violet indescribable” of Lake Shinji, “the ghostly love colors of a morning steeped in a mist soft as sleep,” or the pond frogs in his garden whose “croaking is an omen of rain.”

However, as Donald Richie notes in Lafcadio Hearn’s Japan, “[Hearn] always retained an independence of thought and this grew stronger the longer he lived in the country. Indeed, his is the first objective voice we hear above the clamor of the Orientalists seeking to love or to hate.”

As Hearn tempered his romantic inclinations, it allowed the Japan of his imagination and the Japan he actually experienced to merge into one complete picture. And it’s because of this adaptability that he blossomed into one of the finest writers of his age. “Never perhaps was scientific accuracy of detail married to such tender and exquisite brilliancy of style,” said his mentor, Basil Hall Chamberlain.

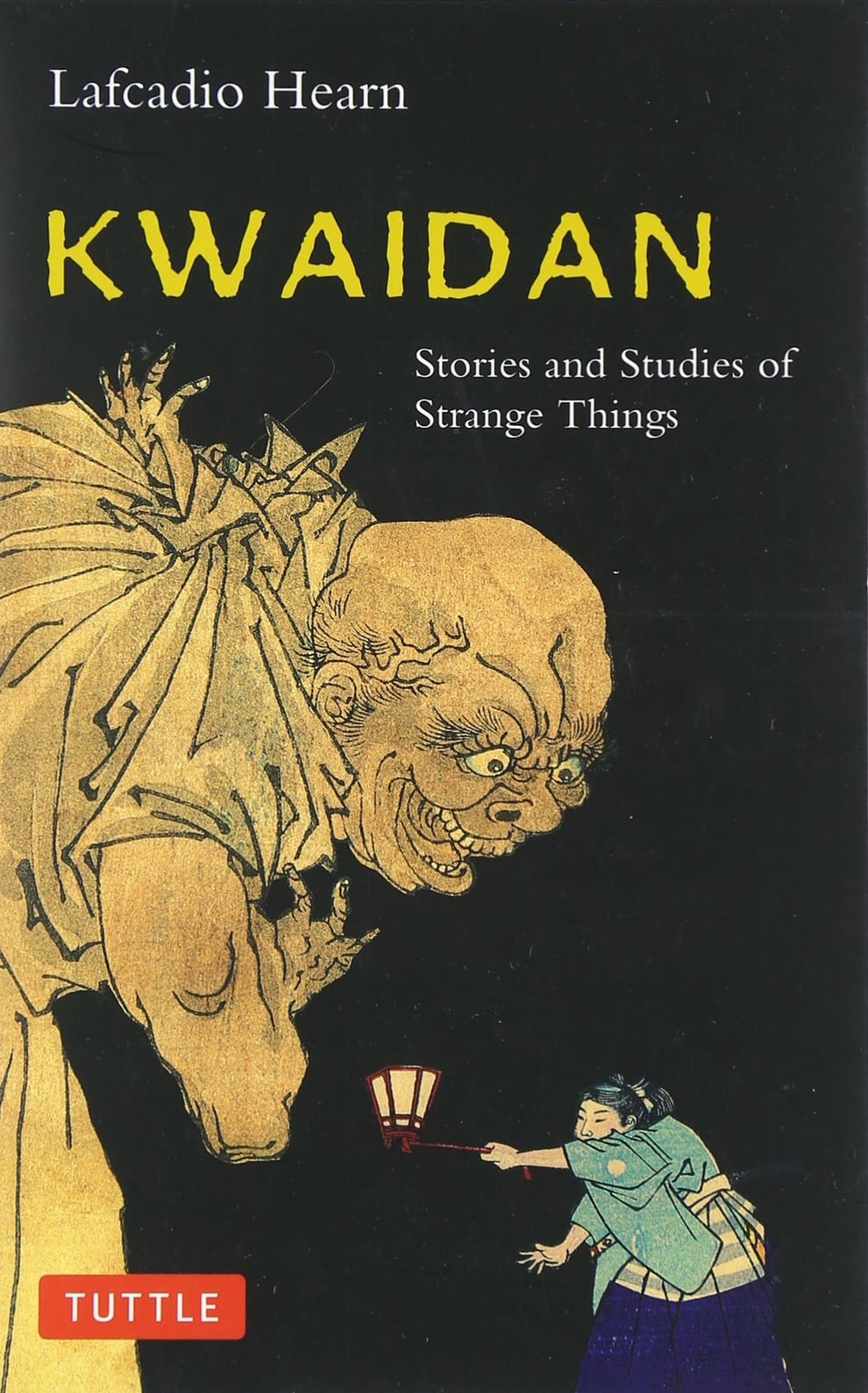

The Wandering Ghost

Hearn lived in Japan until his death in 1904, his bibliography growing each year as he explored the “old ways” striving to survive while Japan succumbed to the forces of globalization. In the West, Hearn is closer to a cult figure than a bona fide member of the canon. In his adopted homeland, though, he remains a literary treasure, with books like Kwaidan and Glimpses of Unfamiliar Japan still appearing on Japanese literature curricula.

Hearn’s legend is inextricable from regional folktales, which he reimagined in lucid and gripping prose. He sought out these stories during his travels in the provinces, visiting priests and merchants, speaking to farmers and villagers, and listening to the songs of the street. Folklore was part of the poetry Hearn saw everywhere in Japanese life. He believed it revealed the true soul of Japan. “The ghostly,” he wrote, “represents always some shadow of the truth.”

Hearn understood that the underpinning structure of traditional life shaped people’s sense of identity. He saw that science and spirituality didn’t need to be foes. And he traveled with an open ear and open mind, always unencumbered by prejudices. It’s for these reasons, among many others, that we still read him today.