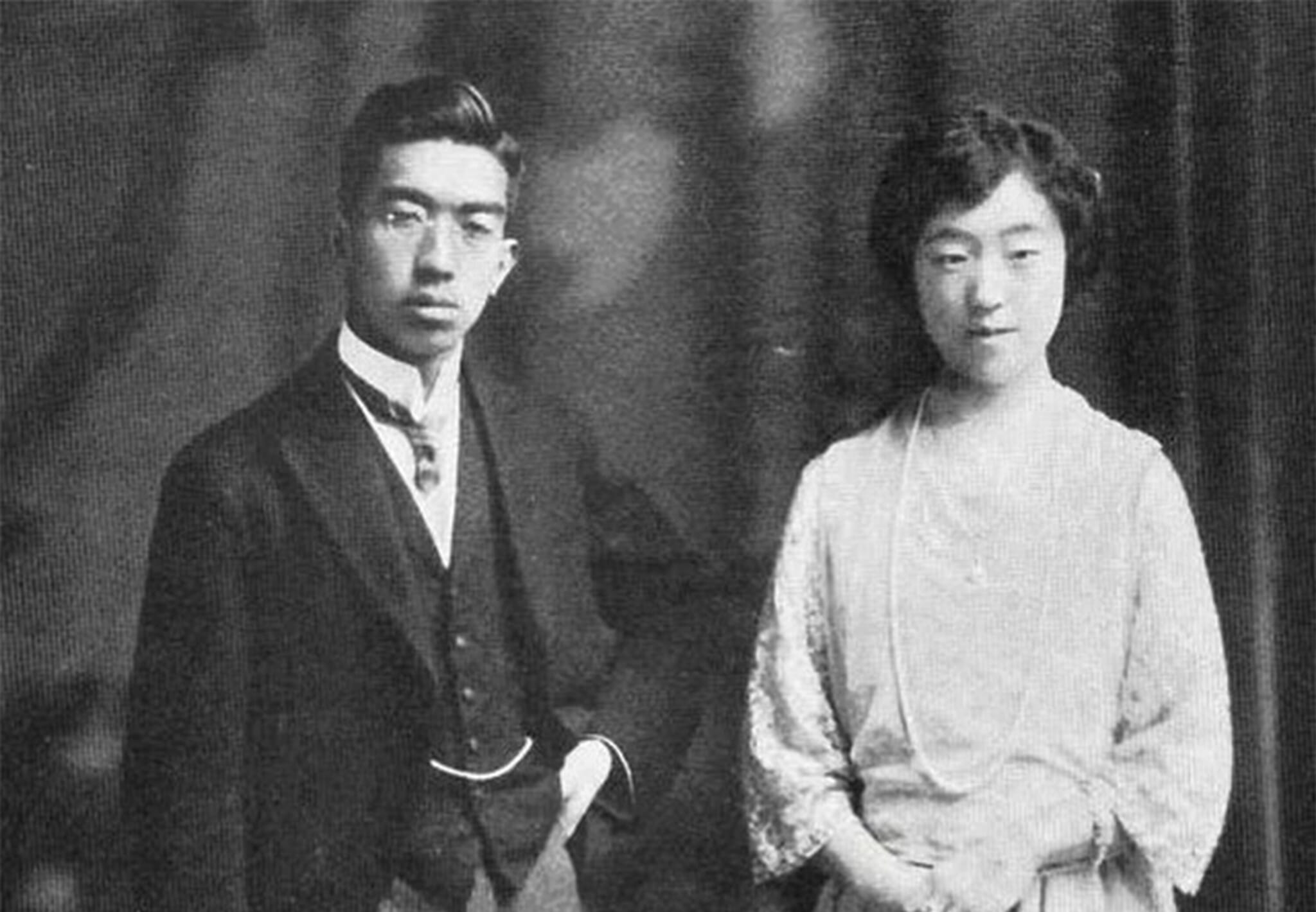

On this day 100 years ago, Crown Prince Hirohito married his distant cousin, Princess Nagako, the first daughter of Prince Kuni Kuniyoshi. Delayed due to the Great Kanto earthquake in 1923, the future emperor and empress tied the knot at a lavish Shinto ceremony in Tokyo. Crowds lined the streets to catch a glimpse of the imperial procession, though they had to bow their heads as it passed, as they weren’t allowed to look at the couple’s faces.

The last empress of noble blood, Nagako was known as a fierce lady behind the walls of the palace, yet always appeared in public with a big smile. Attuned to court customs, she displayed a subject’s deference to her husband, who at the time of his succession was viewed as a divine figure in Japan. He was said to have described their union as “a source of solace and contentment.” Lasting just shy of 65 years, it was the longest imperial marriage in Japanese history, yet had the country’s most powerful man had his way, the relationship wouldn’t have gotten past the engagement stage.

Powerful Opposition to the Engagement of Hirohito and Nagako

Breaking with royal tradition, Hirohito was given permission to choose his own bride. In 1914, his mother, Empress Sadako, invited a number of girls of suitable rank for a tea ceremony at the Concubines’ Pavilion in the Imperial Palace. Hiding behind a sliding screen, Hirohito selected Nagako as his future wife. She had no say in the matter. They got engaged in 1918 when the pair were still in their teens. In the six years that followed, they only met nine times and always with a chaperone.

The engagement proved controversial due to Nagako’s lineage. While she was a princess by birth, she wasn’t a descendant of one of the five regent houses (go-sekke) of the Fujiwara clan, from which the vast majority of imperial brides came. Subsequently, some members of the Genro — an unofficial designation of elderly statesmen who advised the emperor — felt she wasn’t suitable for the position. The most vocal opposition came from Field Marshal Prince Aritomo Yamagata.

A military commander who was twice elected as the prime minister of Japan, Yamagata was widely considered the “father” of Japanese militarism and the country’s most preeminent statesman. He believed Princess Tokiko of the Ichijo-oka family was a better option for the prince. His main reason for not endorsing Nagako was most likely because her mother was the daughter of the last daimyo (feudal lord) of the Satsuma clan, which was the main rival to his own Choshu clan. Yamagata attempted to dissuade the crown prince from marrying Nagako by emphasizing a strain of color blindness in the bride-to-be’s lineage that he claimed could damage the imperial bloodline.

A Delayed Wedding

Yamagata’s campaign, however, only damaged his own reputation and career and he was forced to give up his political positions and noble status before his death in 1922. Prince Kuni vowed to take his own life and kill Nagako if the engagement was canceled. He called on nationalists to stage large rallies in Tokyo denouncing plots against his daughter. She also had the support of Emperor Taisho, who dismissed the stories regarding color blindness in her family. With the path clear, they were scheduled to tie the knot in the fall of 1923.

However, the Great Kanto earthquake on September 1 put paid to that idea. The wedding was consequently postponed to the following year. There was, though, more drama to come before they could finally say “I do.” On December 27, 1923, Daisuke Nanba attempted to assassinate Hirohito in what became known as the Toranomon Incident — as it occurred at the Toranomon intersection. The crown prince was on his way to the opening of the 48th session of the Imperial Diet when a shot was fired at his carriage. While the bullet shattered a window and injured a chamberlain, Hirohito walked away unscathed.

Less than a month later, he wed his princess. A loyal husband, Hirohito abandoned his 39 concubines, breaking with royal tradition. In the first seven years of marriage, Nagako bore four daughters, though Sachiko died of pneumonia aged five months and 27 days. As the years passed, the pressure on the pair to produce a male heir intensified, yet Hirohito remained monogamous. Akihito’s birth in 1933 subsequently sparked nationwide celebrations. “The happiest moment in my life,” was how Nagako described it. The couple, who became emperor and empress on December 25, 1926, had two more children.

The Final Years of Hirohito and Nagako

In his final years, the late emperor reportedly told his then-chamberlain Shinobu Kobayashi that he did not wish to live much longer. According to an entry dated April 7, 1987, in Kobayashi’s diary, Hirohito said, “There is no point in living a longer life by reducing my workload. It would only increase my chances of seeing or hearing things that are agonizing.” He added, “I have experienced the deaths of my brother and relatives and have been told about my war responsibility.” Japan’s longest serving monarch, Hirohito (posthumously honored as Emperor Showa) died at 6:33am on January 7, 1989, aged 87.

After his death, the Imperial Household Agency announced that doctors discovered he had duodenal cancer two years earlier. Nagako, who became empress dowager, was unable to attend her husband’s funeral due to her own poor health. She had been in a wheelchair since 1980 and was rarely seen in public in her later years. In 1995, she became the longest-living empress dowager of Japan, overtaking the record held by Empress Kanshi, who died in 1127. Nagako (posthumously honored as Empress Kojun) passed away on June 16, 2000. She was 97.