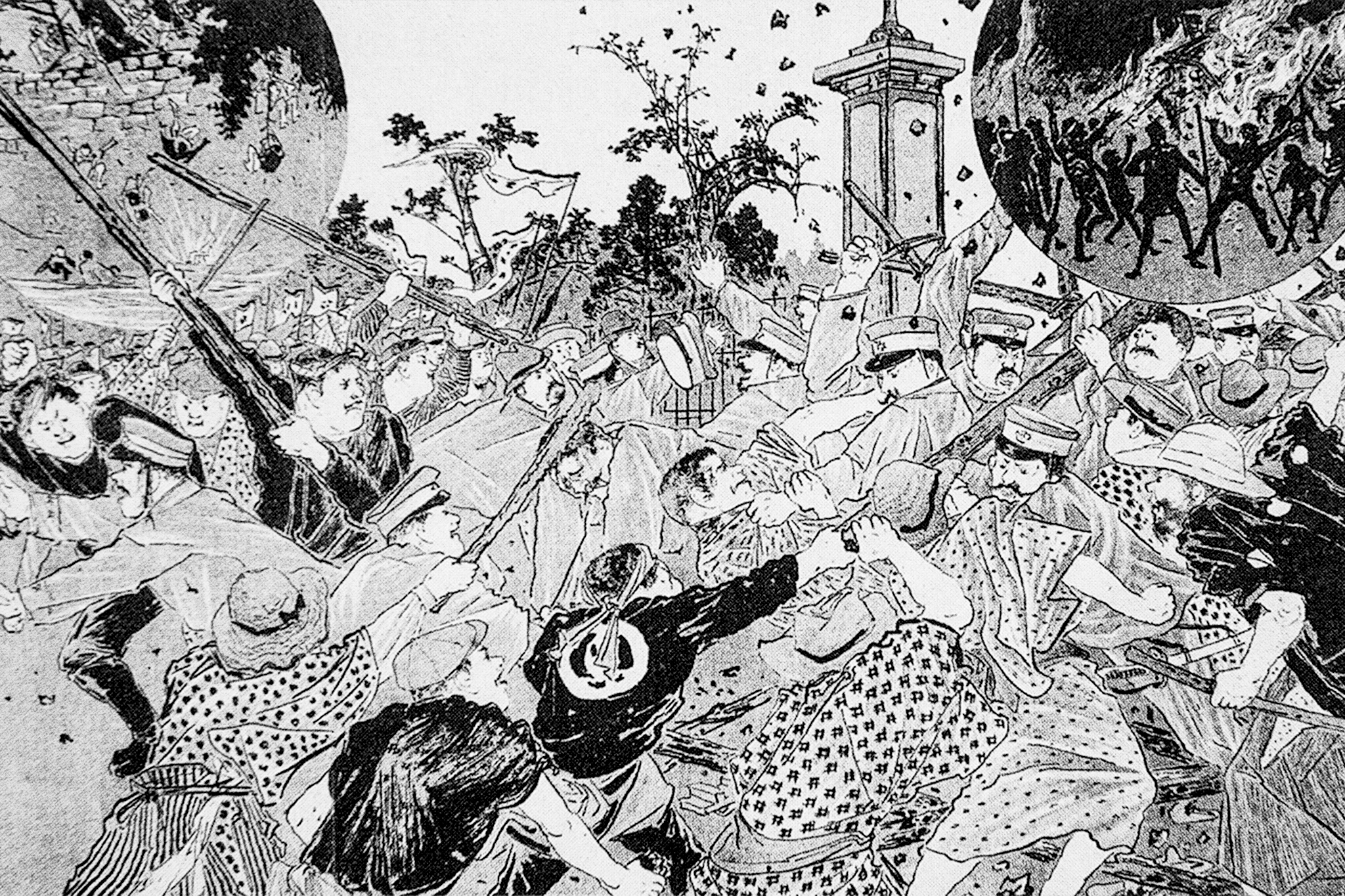

Hibiya Incendiary Incident (September 5-7, 1905, Tokyo)

When the Russo-Japanese War finally ended in 1905, Japan’s negotiators were too tired and too many people had died for the country to chase significant demands. When the peace treaty was announced, it contained a host of concessions to the Russians. The treaty even gave Russia back the land that Japan had won (it’s Sakhalin, for anyone interested). Japanese citizens were furious. They couldn’t understand why so many concessions had been made. It seemed as though the war was fought and people had died for nothing.

In response, 30,000 protesters broke into Hibiya Park on September 5 of that year to hold a short rally. This was followed by another rally close by. Once the second one had got the listeners riled up, around 2,000 people marched toward the Imperial Palace, wreaking havoc along the way. Rioters attacked government buildings, police boxes and more. The violence spread.

The police had little control over the rioters. It lasted three days before it was subdued with the aid of the military. With 17 fatalities, 311 arrests and more than 70 percent of Tokyo’s police boxes destroyed, the rioters certainly didn’t hold back.

The Hibiya Riots set off a period of unrest and violence around the country, which ended 13 years later.

Credit: https://files.libcom.org/files/1918%20Rice%20riots%20and%20strikes%20in%20Japan.pdf

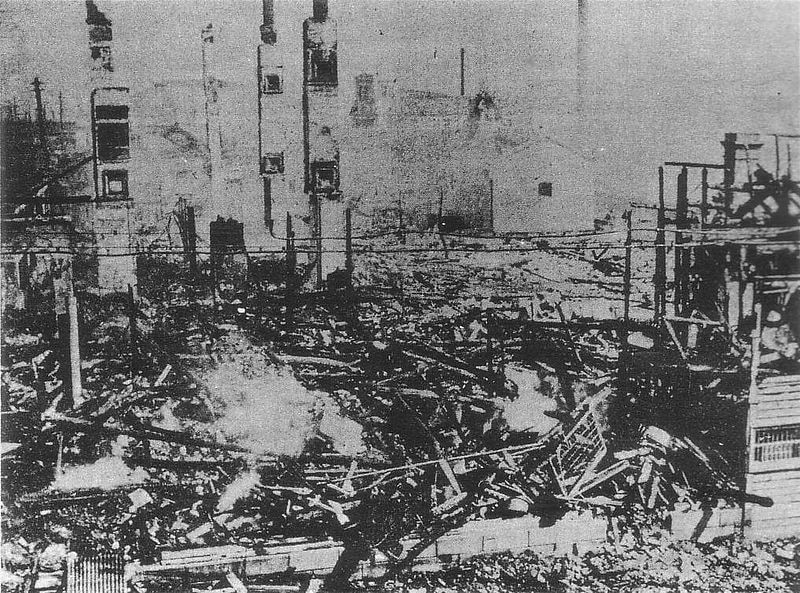

Rice Riots (1918, Toyama)

The Rice Riots, also known as Kome Sodo, were started by a group of women in Toyama, due to the rising cost of living. It began with peaceful petitioning, but the cause soon struck a chord with workers across the country. This led to a nationwide uprising, estimated to have involved some 10 million people.

From Kobe to Osaka and Tokyo, the protests began at the end of July 1918 and finished in September of the same year. Workers were angry about the prices of commodities such as rice. Both producers and consumers chanted “sell rice cheaply” and “down with the traders.” Ultimately, rioters were subdued by the force of the military, but the Rice Riots led to the toppling of Masatake Terauchi’s government.

Terauchi was replaced by the first commoner and first Christian to be appointed prime minister of Japan, Takashi Hara. It was a great coup for the rioters. Japan’s riotous nature, however, had been subdued. For the time being, at least.

Credit: Life Magazine Vol. 32 No. 19. May 12, 1952

Bloody May Day (May 1, 1952, Tokyo)

After World War II, Japan was occupied by the US in order to ratify its post-war treaty. What had been a peaceful transition of power ended in violence shortly after Japan gained its sovereignty back. This is known as the Bloody May Day riot.

As a response to the treaty signed on April 28, 1952, which allowed the United States to maintain military forces on Japanese soil, a seemingly peaceful rally of 300,000 people in Meiji Park was set to be held by the labor unions. However, when the first speaker stepped up, protestors, who had hidden in the front row, got up and stormed the stage. The crowd then marched to the palace, overturning and smashing American-made cars along the way. They also chanted anti-US sentiments such as “Yankee, Go Home.” When the crowd reached the palace, they clashed with around 400 riot police who had been waiting for them. The rioters gained the upper hand until more reinforcements arrived, accompanied by tear gas and shots fired overhead. At least two people died and around 1,500 protesters and 800 police officers were injured.

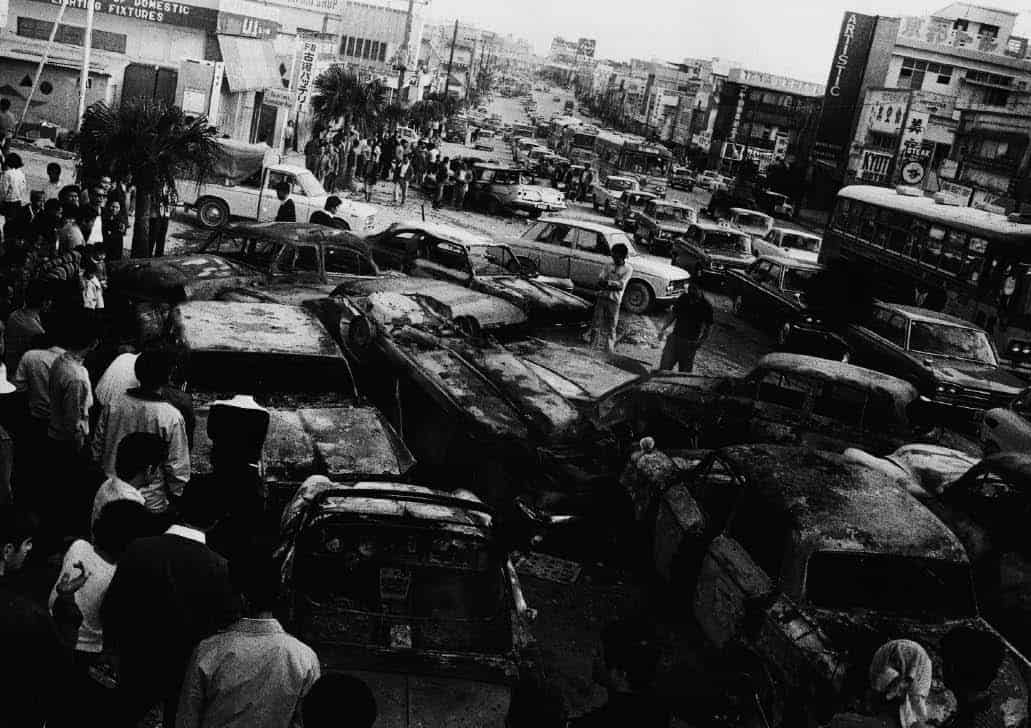

Koza Uprising Credit: www.public-history-weekly.degruyter.com

Koza Uprising (December 20, 1970, Okinawa)

The occupation of Okinawa by the US, which ended in 1972, was largely peaceful except in 1970. Throughout the years, many incidents led Okinawans to believe that the occupiers were above the law. Then, in September 1970, an Okinawan housewife was killed in a hit-and-run incident by three US soldiers. They were acquitted in court. After this, tensions began to rise, culminating in a riot on December 20, 1970, after an American car in Koza hit an Okinawan man. The Americans went to check on the man to see if he was okay. He was, but some Okinawans close by had seen what happened.

The Okinawans berated the servicemen, demanding justice for what they had witnessed, gradually drawing a large crowd. The incident escalated quickly and soon 5,000 people had joined against 700 American military police. By the end of the night, approximately 60 Americans and 20 Okinawans had been injured in the fighting. Around 80 cars were burned and some buildings were destroyed.

Railway Rampage (March 13, 1973, Saitama)

From March 5, 1973, railway workers began to protest at their punishing conditions, demanding their hours be reduced and safety improved. The trains were packed each day, several times over the legal limit, and railway workers were rightly worried. In protest, drivers began to drive trains slower and slower, in a move nicknamed “the slowdown.” A journey which would usually take 37 minutes, for instance, began to last for 3.5 hours.

On March 13, 1973, at Ageo Station in Saitama, as a result of “the slowdown,” around 5,000 commuters were left stranded, unable to get into Tokyo. Furious, they revolted and took the stationmaster hostage, while also stoning the unmoving trains. The riot spread to other lines near Tokyo, including the Kawagoe and Tohoku lines. The police couldn’t control the protesters. They had to call for backup from Gunma and specialized riot police. Service finally resumed in the afternoon.

Railway workers continued their protests in the form of strikes and protests. Unfortunately, no solution was found, and the train service was privatized over 10 years later.

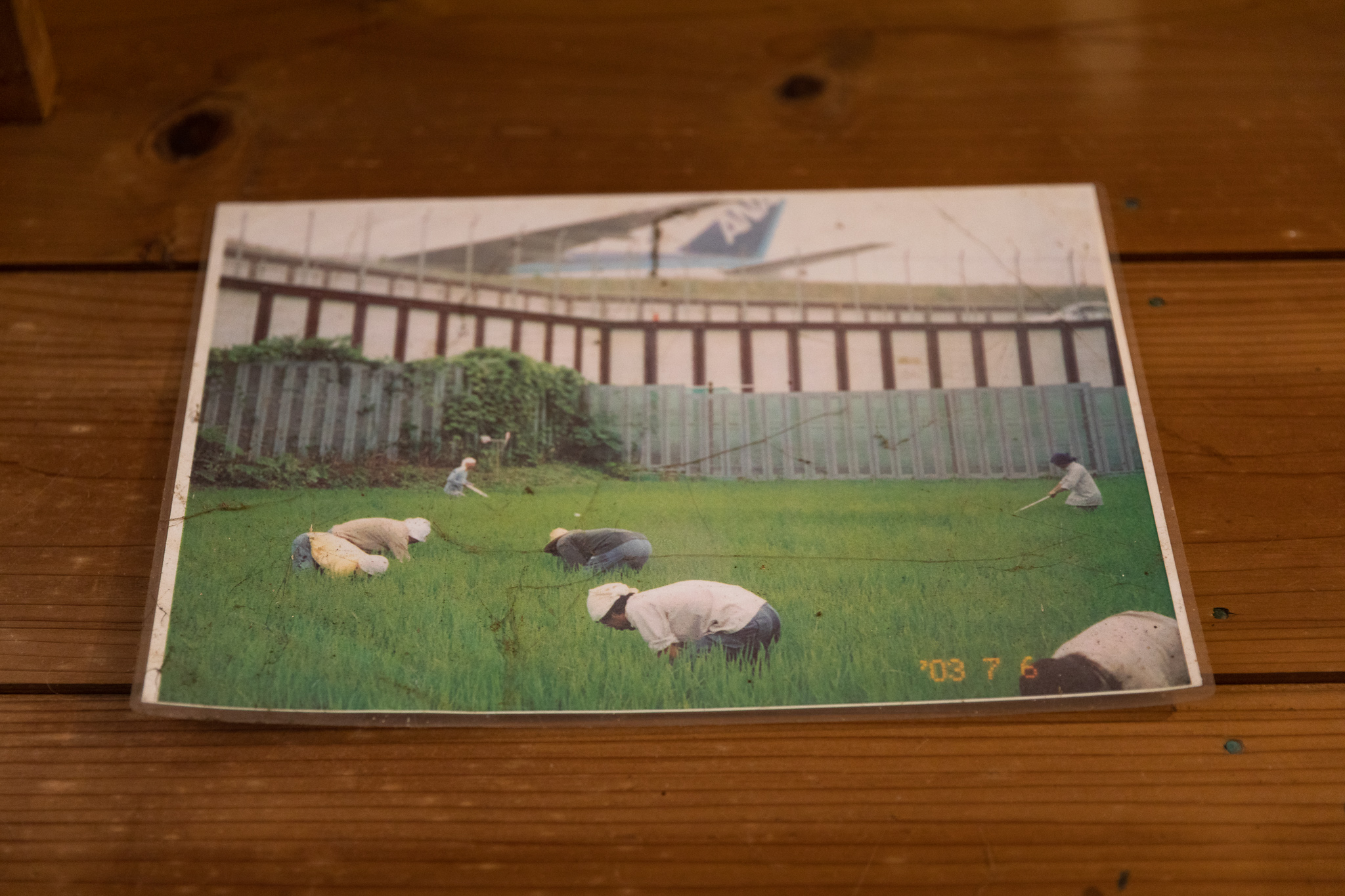

Sanrizuka Struggle (1966-present, Chiba)

In 1966, 200 farming families in the countryside of Chiba Prefecture found out that the council had decided to knock down their homes and build Narita Airport. They received this information via a newspaper. No consultation, no contact, simply a chilling article that confirmed their fate. Confused, they rushed to the city hall and found out it was true.

The farmers were ready to drop tools and don helmets at any moment. Image Anna Petek

While there was some acceptance, a strong core of farmers refused to leave their homes. They formed a union which attracted the attention of various political groups at the time, many who moved to be closer to the site. The rioters defended the land at all costs. They refused to leave and obstructed any attempts to gain access. Notable battles with the police happened in 1971, 1978 and 1985. The government was arguably just as violent as the farmers, aiming to take the land at all costs. Over the years, tens of thousands of lives have been affected by the struggle. Many died directly or indirectly as a result.

Even though the majority of the protestors accepted an agreement in 1991, there were a couple who refused to acknowledge it. The last remaining farmer (covered by the BBC, as shown above) was removed from his farm in February 2023, but has vowed to fight on.