On Saturday, Japan’s ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) chose its fourth leader in five years, Sanae Takaichi. Given the party’s recent record, the public is unlikely to be feeling overly confident about Shigeru Ishiba’s successor lasting too long in the role. Takaichi will be aiming to convince LDP members of the Diet and dues-paying party members from across Japan that she can be the one to buck the trend and stay in power for a few years, like the names below. For our latest List of 7, we are looking at Japan’s longest-serving prime ministers.

Shinzo Abe

Japan’s longest-serving prime minister, Shinzo Abe first took up the government’s top position in September 2006. The nation’s first leader born after World War II, he lasted just 12 months. His first term was dominated by scandals, including the government’s confession that it had lost track of pension records linked to more than 50 million claims. Two months after the LDP and New Komeito lost control of the Upper House, Abe resigned due to his struggles with ulcerative colitis.

The Yamaguchi Prefecture native took the reins again in 2012. From Abenomics to the infamous Abenomasks during the COVID-19 pandemic, he certainly left a bigger mark the second time around. A hawkish and divisive political figure, Abe tended to downplay Japan’s imperial-era atrocities. He also called for Article 9 of the Constitution, which renounces war and bans Japan from maintaining any war potential, to be revised. He resigned in 2020, again citing health reasons.

Two years later, Abe was assassinated by Tetsuya Yamagami.

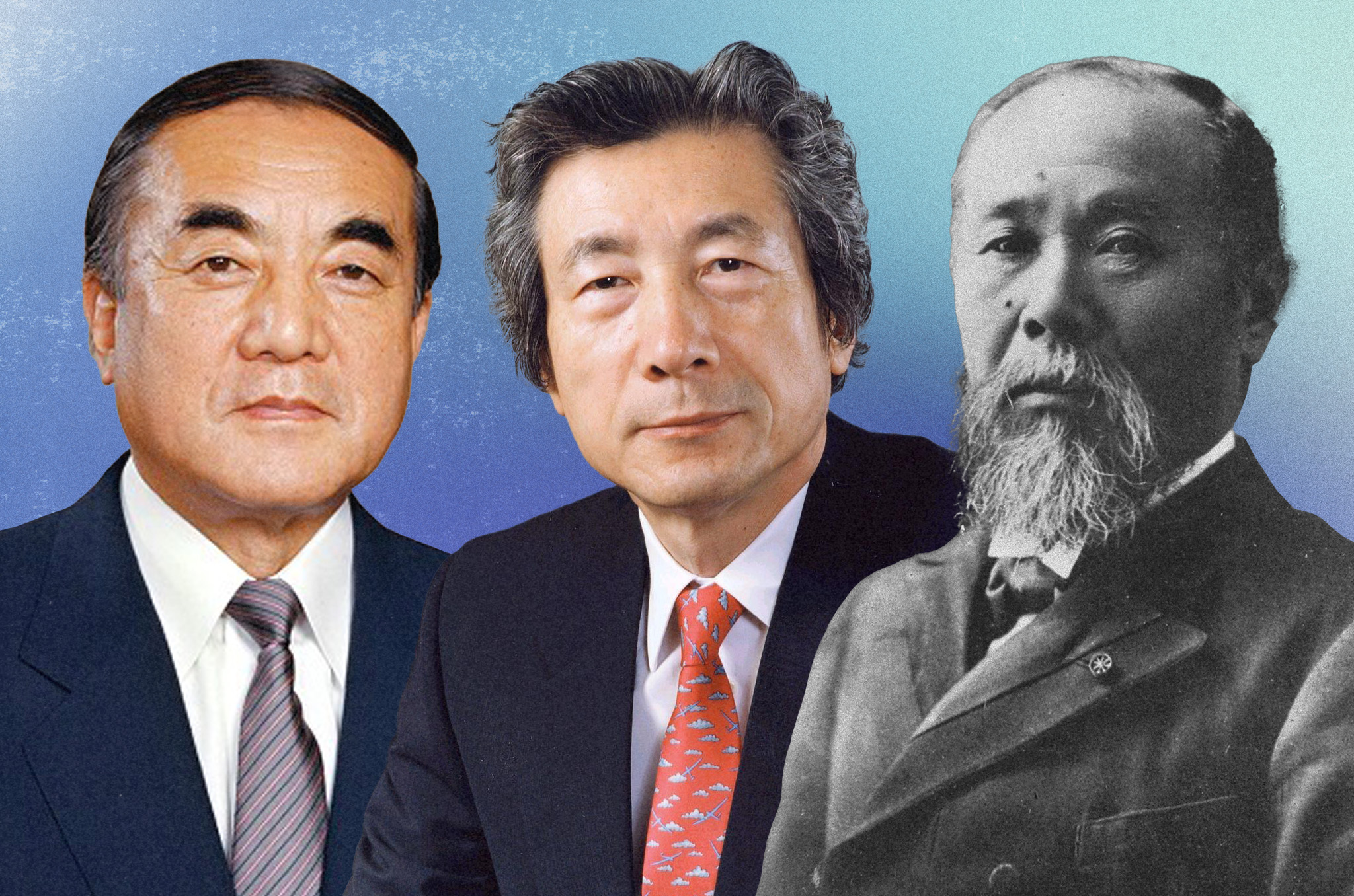

Katsura Taro

The second-longest serving Japanese prime minister after Abe was Prince Katsura Taro. The former governor-general of Taiwan served as the country’s leader three times, starting in 1901. He was forced to quit four and a half years later, despite Japan’s decisive victory in the Russo-Japanese War. Public outrage forced him out after Japan failed to secure an indemnity from Russia during the Treaty of Portsmouth that followed the conflict. This led to the Hibiya Riots, which resulted in the deaths of 17 people.

The most significant event during his second tenure as prime minister was the 1910 Kotoku Incident, a socialist-anarchist plot to assassinate Emperor Meiji. Twelve conspirators were subsequently hanged, including Sugako Kanno, the first woman with the status of political prisoner to be executed. It was also noteworthy for the Japan-Korea Annexation Treaty. Six months after Emperor Meiji’s death in July 1912, Katsura was appointed as prime minister for a third time.

He lasted just two months, though, and in October 1913, died of stomach cancer.

Eisaku Sato

The brother of Abe’s grandfather — the former Prime Minister Nobusuke Kishi — Eisaku Sato led the country between 1964 and 1972. Not long after taking power, he visited Okinawa, stating, “The postwar era will not end so long as Okinawa is not returned.” He then raised the issue in a meeting with US President Lyndon B. Johnson in 1967. Four years later, the Okinawa Reversion Agreement was signed simultaneously in Tokyo and Washington, returning the prefecture to Japanese sovereignty. It took effect on May 15, 1972.

Sato was also the prime minister when Japan signed the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty in 1970. Four years later, he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize “on the grounds that he represented the Japanese people’s desire for peace.” It was seen as a controversial choice, as his period as premier was marked by a series of corruption scandals. His wife, Hiroko, also said that he beat her in an interview with novelist Shusaku Endo titled “My Tearful Early Days of Marriage.”

Sato passed away in 1975.

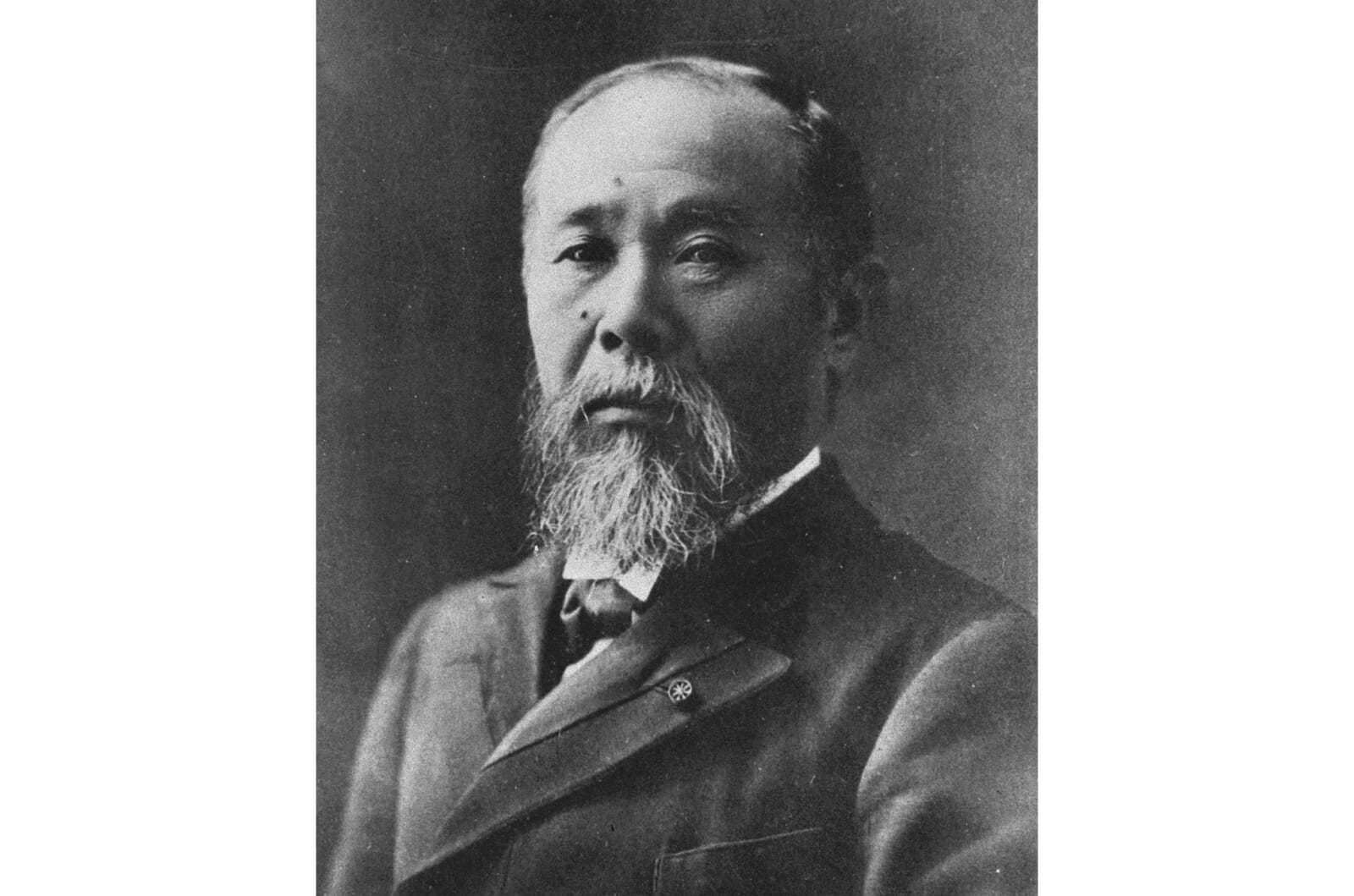

Hirobumi Ito

Japan’s first prime minister, Hirobumi Ito served as the country’s leader four times, starting in 1885. He was the driving force in replacing the Dajokan (the Great Council of State) and establishing the modern cabinet system in Japan, to which he was appointed leader. Three years earlier, he had been sent to Europe to survey constitutional systems in various countries. Upon his return, he was the principal framer of the Meiji Constitution, which was promulgated in 1889. It became the nation’s foundational law until the enactment of the new Constitution of Japan in 1947.

Ito, who played an instrumental role in establishing Japan’s modern fiscal, monetary, banking and public finance systems, also pursued expansionist foreign policies. He oversaw Japan’s involvement in the First Sino-Japanese War and was a key figure in laying the groundwork for Korea’s annexation by Japan in 1910. Following the Japan-Korea Treaty of 1905, which made Korea a protectorate of Imperial Japan, Ito was made the first Japanese resident-general of Korea.

In 1909, Ito was assassinated by Korean independence activist and nationalist An Jung-geun at Harbin Station in Manchuria.

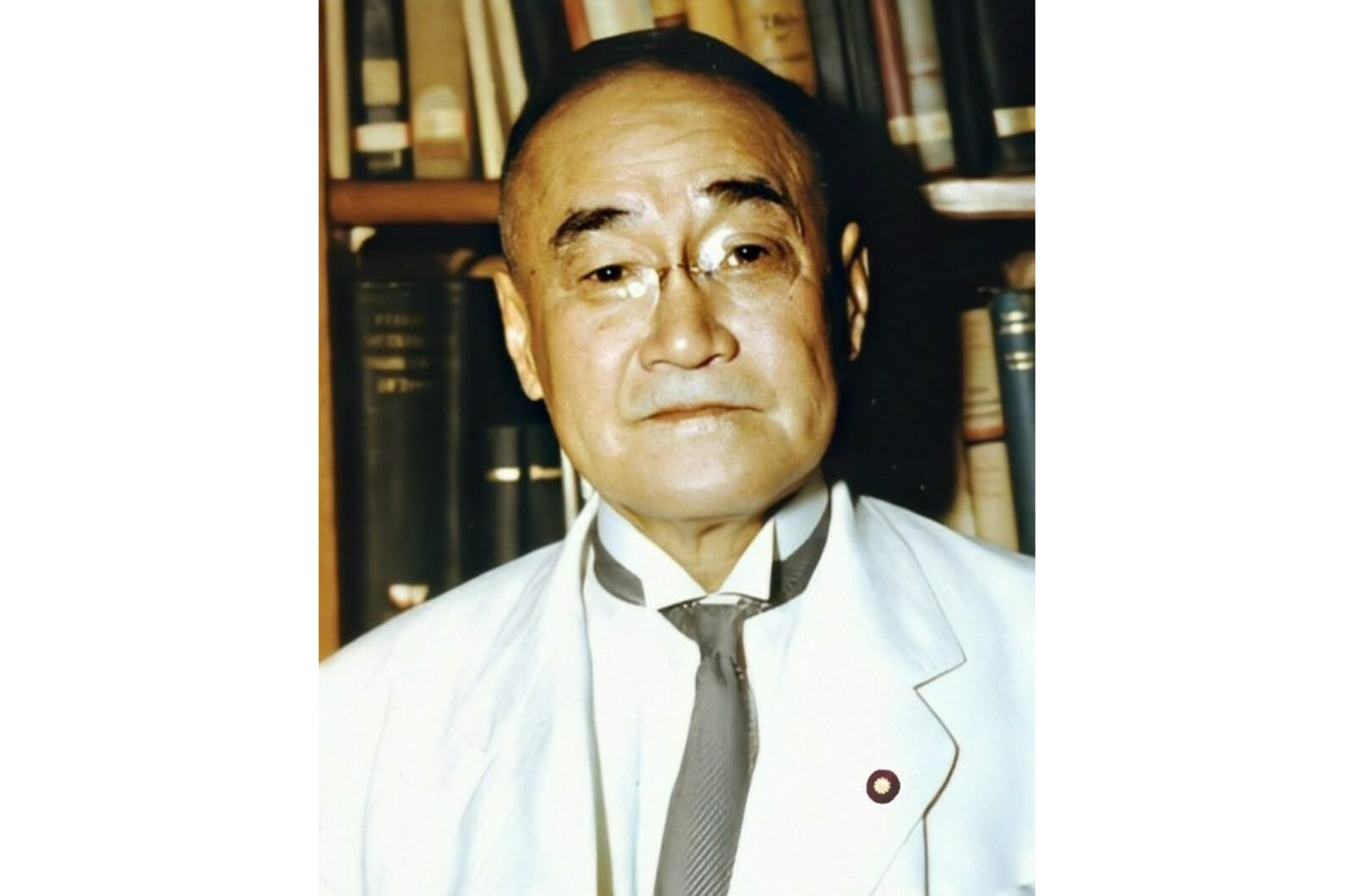

Shigeru Yoshida

Described as the architect of modern Japan, Shigeru Yoshida served as prime minister between 1946 and 1947 and then again from 1948 to 1954. His appointment to the post came after Ichiro Hatoyama, whose party had earned the most seats in the 1946 election, was purged from public office by the US occupation authorities. Hatoyama then approached Yoshida to take his place. During his first term as leader, Yoshida oversaw the adoption of the postwar Constitution of Japan. At the 1947 general election, Yoshida’s Liberal Party lost to the Japan Socialist Party, but he was back in power within 18 months.

In 1949, he was forced to accept the Dodge Line — a financial contraction policy drafted by economist Joseph Dodge — that caused severe short-term hardship, but ended hyperinflation. Two years later, Yoshida signed the Treaty of San Francisco, which restored Japan’s sovereignty and independence from the Allied occupation. That same year, the Yoshida Doctrine emerged with the aim of reconstructing Japan’s domestic economy while relying heavily on the security alliance with the US. He was replaced by Hatoyama in 1954.

Yoshida died in 1967 after being baptized on his deathbed.

Junichiro Koizumi

A maverick leader, Junichiro Koizumi served as Japan’s prime minister between 2001 and 2006, during which time he was well known for his love of Elvis Presley. He even sang “I Want You, I Need You, I Love You” with Tom Cruise. Another celebrity encounter occurred with Richard Gere. The pair danced together in his office. The Hollywood stars used the words “extraordinary” and “charming” to describe him. As for the Japanese public, they were similarly impressed early on. His first cabinet had a record approval rating of 87% in one poll.

Koizumi’s popularity was damaged in 2002, though, when he fired the straight-talking foreign minister, Makiko Tanaka. After she was filmed sobbing, he responded with the words, “Tears are a woman’s ultimate weapon.” That same year, he visited North Korea for a landmark summit meeting with Kim Jong Il. Five abductees were later returned to Japan. At the 2005 Lower House election, Koizumi’s LDP won 296 seats — at the time, the largest share since World War II.

His son, Shinjiro, is one of the leading contenders in the upcoming LDP presidential election.

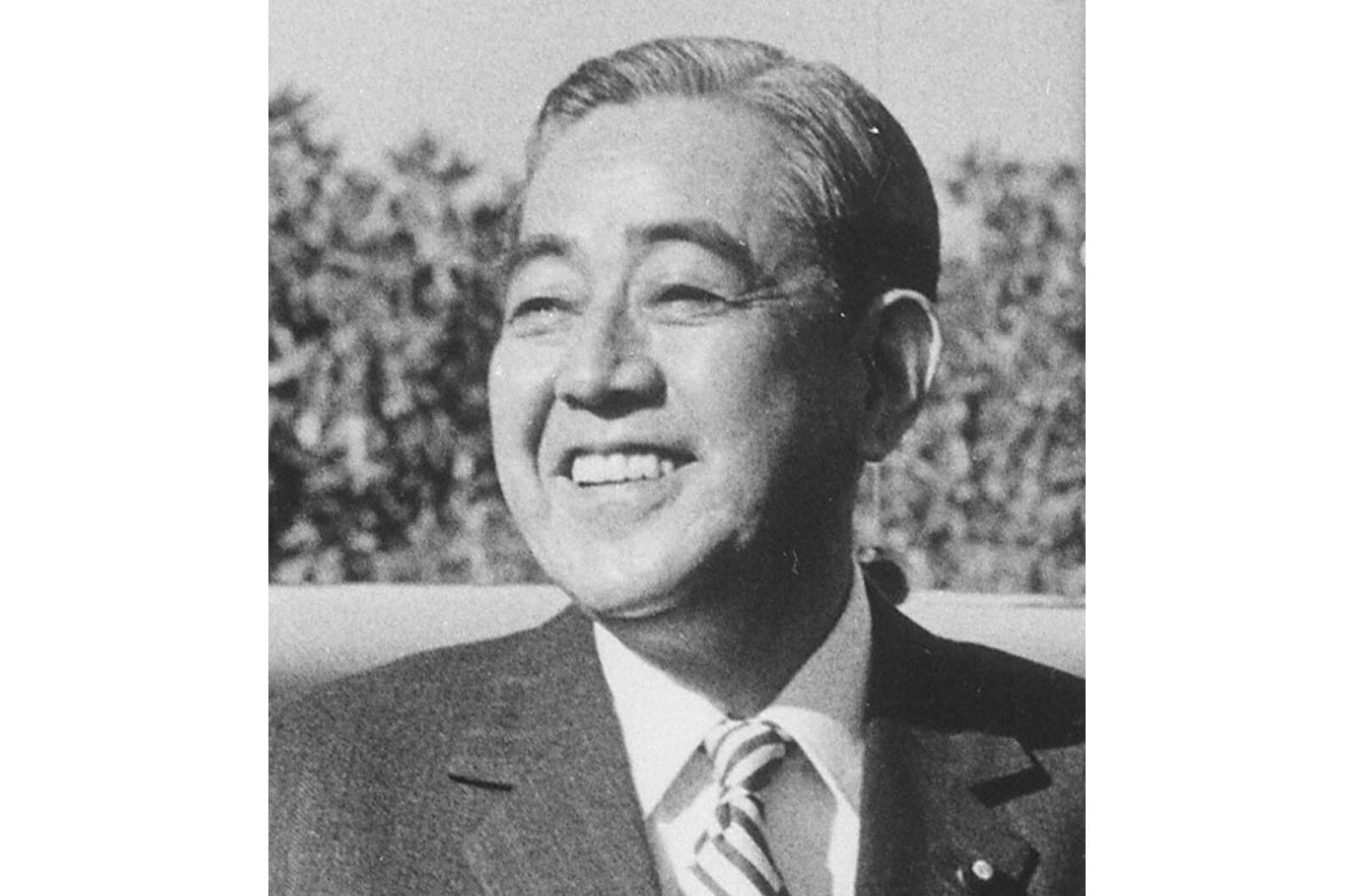

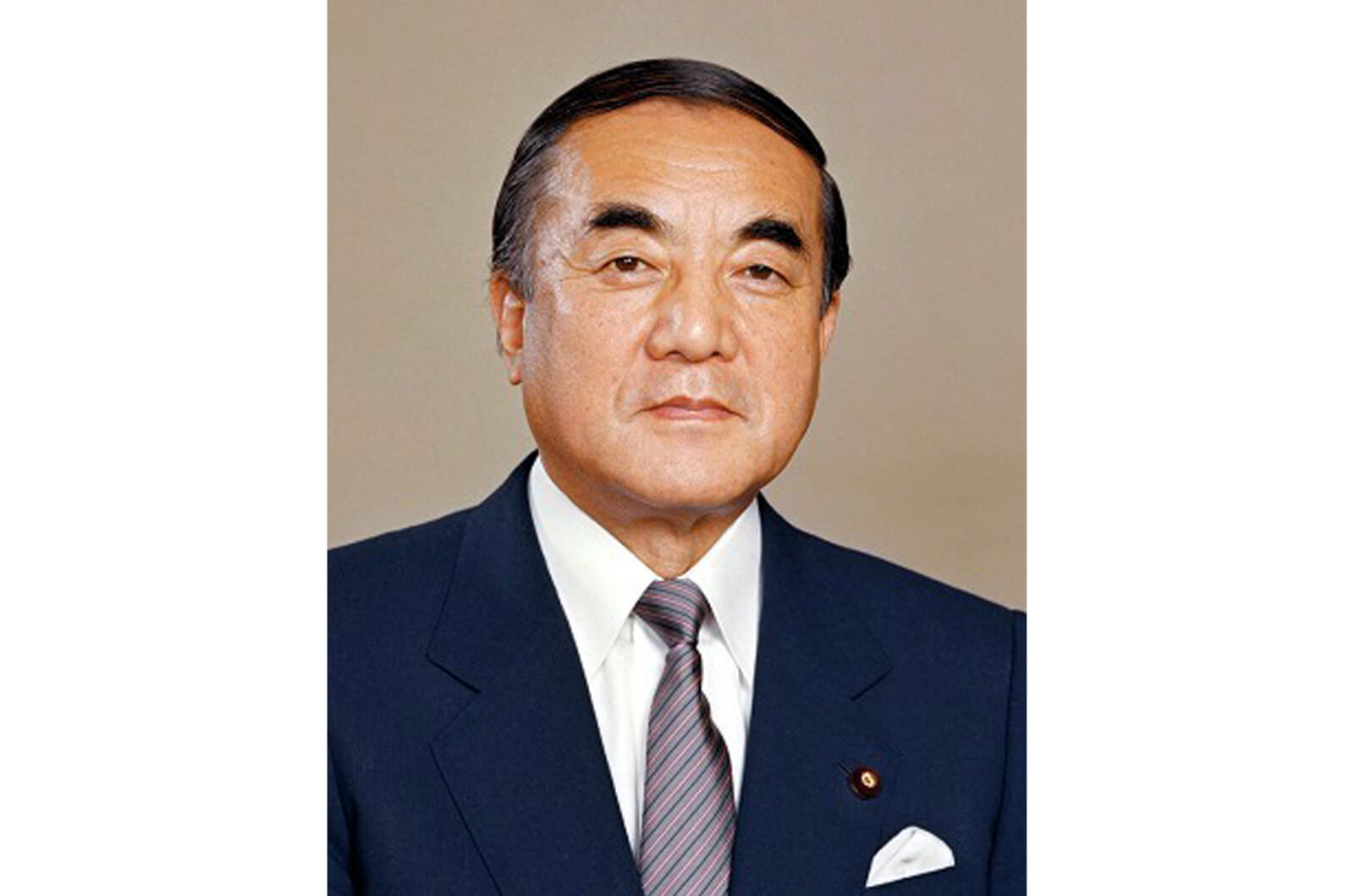

Yasuhiro Nakasone

Before Trump and Abe — even before Bush and Koizumi — there was “Ron and Yasu”: the famous friendship between Ronald Reagan and Yasuhiro Nakasone. The pair tightened US-Japan security ties in the 1980s, as the two countries had shared concerns over the emerging threat from China, the Soviet Union and North Korea. Nakasone used a sports analogy to describe their relationship, stating that Reagan played the role of the pitcher, while he played the catcher. He also formed a close bond with Great Britain’s first female prime minister, Margaret Thatcher.

Nakasone led the country between 1982 and 1987. In 1983, he went to South Korea in what was the first official visit made by a Japanese prime minister since the re-establishment of formal ties between the two countries. Considered an internationalist-minded nationalist, Nakasone was an adherent of nihonjinron, which refers to discourses that promote the idea of Japanese people boasting a biological uniqueness not found in any other race. During his tenure, he privatized the Japanese National Railways and telephone systems.

Nakasone died aged 101 in 2019.