There are more animals than people here where I live,” artist Daisuke Tajima says when we meet online, attempting to hammer home how remote his studio is in the far reaches of Nara Prefecture.

This land of millennia-old wooden temples and hundreds of tame bowing deer will sound like a Ghibli-esque fairytale to many, beautiful and unreal, but it’s the ordinary world where Tajima grew up. For him, conversely, the land of fantasy was a concrete maze of skyscrapers reaching for the heavens like those shown in his favorite animated works, namely Akira and Ghost in the Shell. “That was a different world I could not experience,” Tajima explains. “And only when I was a bit older did I realize these urban spaces are real and exist elsewhere.”

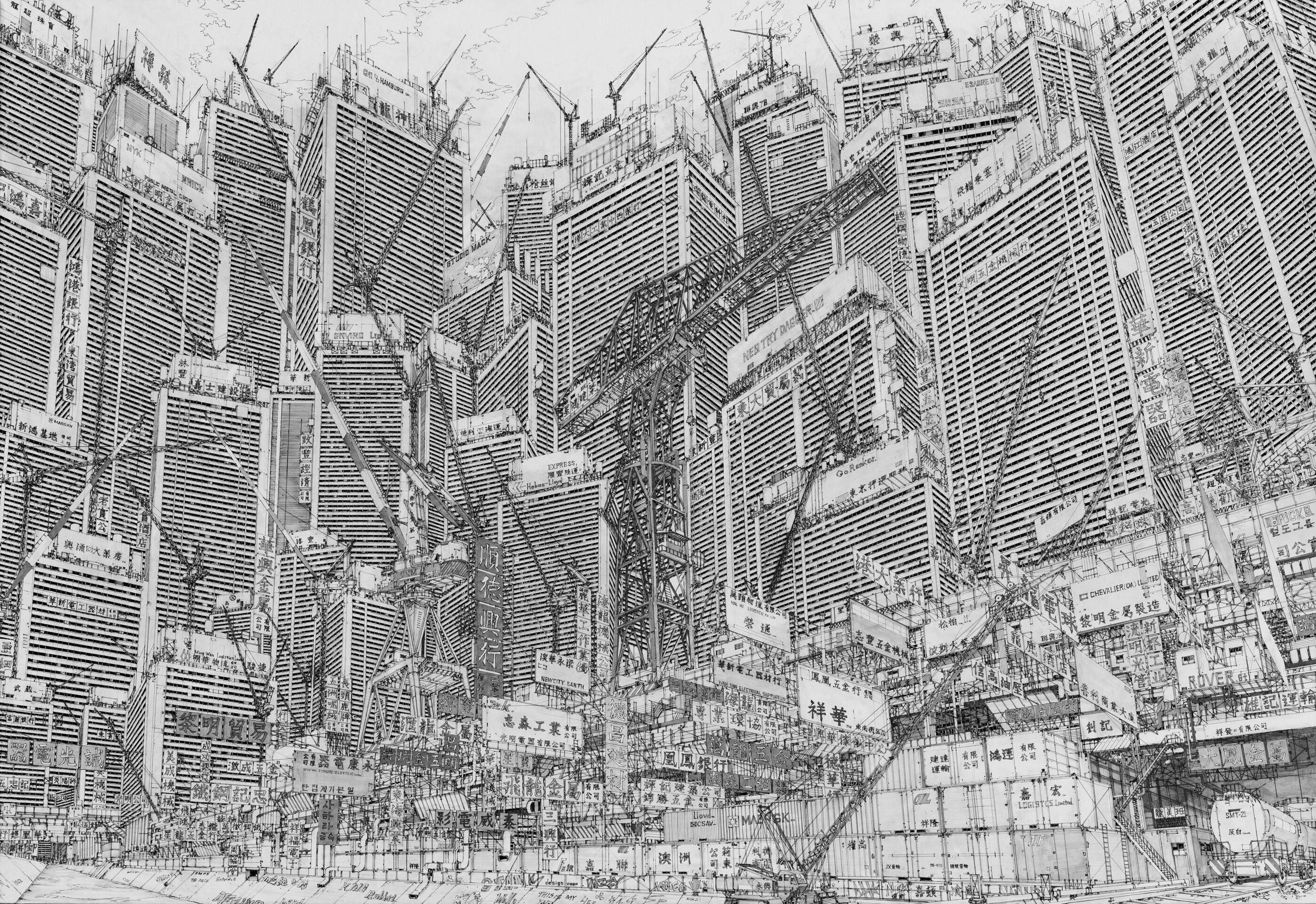

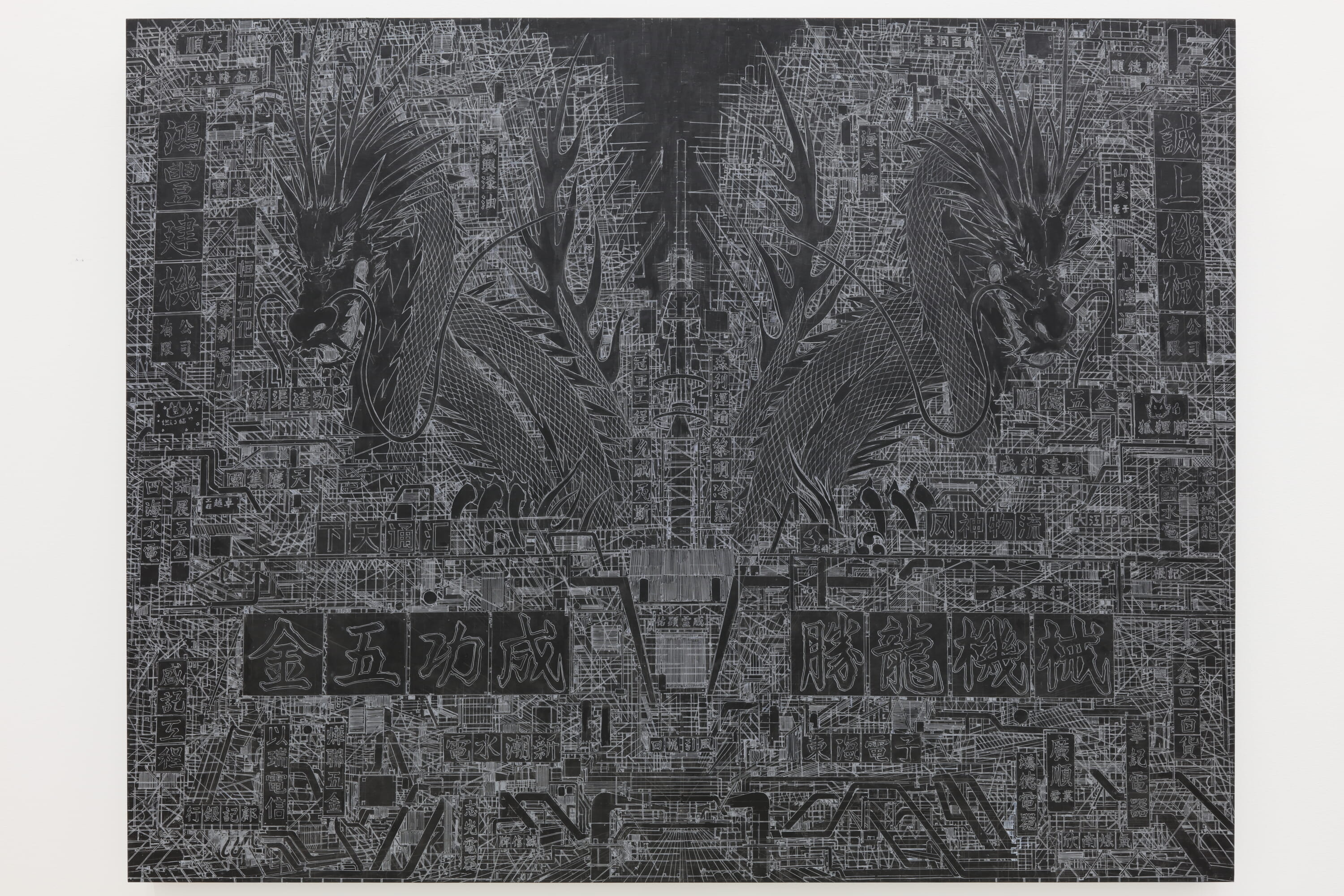

Tajima subsequently started spending as much time as possible traveling to that “elsewhere.” Those concrete and glass jungles are the source of his unending inspiration, as he rebuilds and rearranges his memories while cooped up in his studio in rural Nara without meeting a soul. In turn, his detailed cityscapes busy with construction cranes, kanji signs and the occasional dragon are taking him back to major cities for exhibitions and have won him awards such as the Tokyo Midtown Award Grand Prize in 2015 and the Taro Okamoto Special Award in 2019.

Building a World of Art

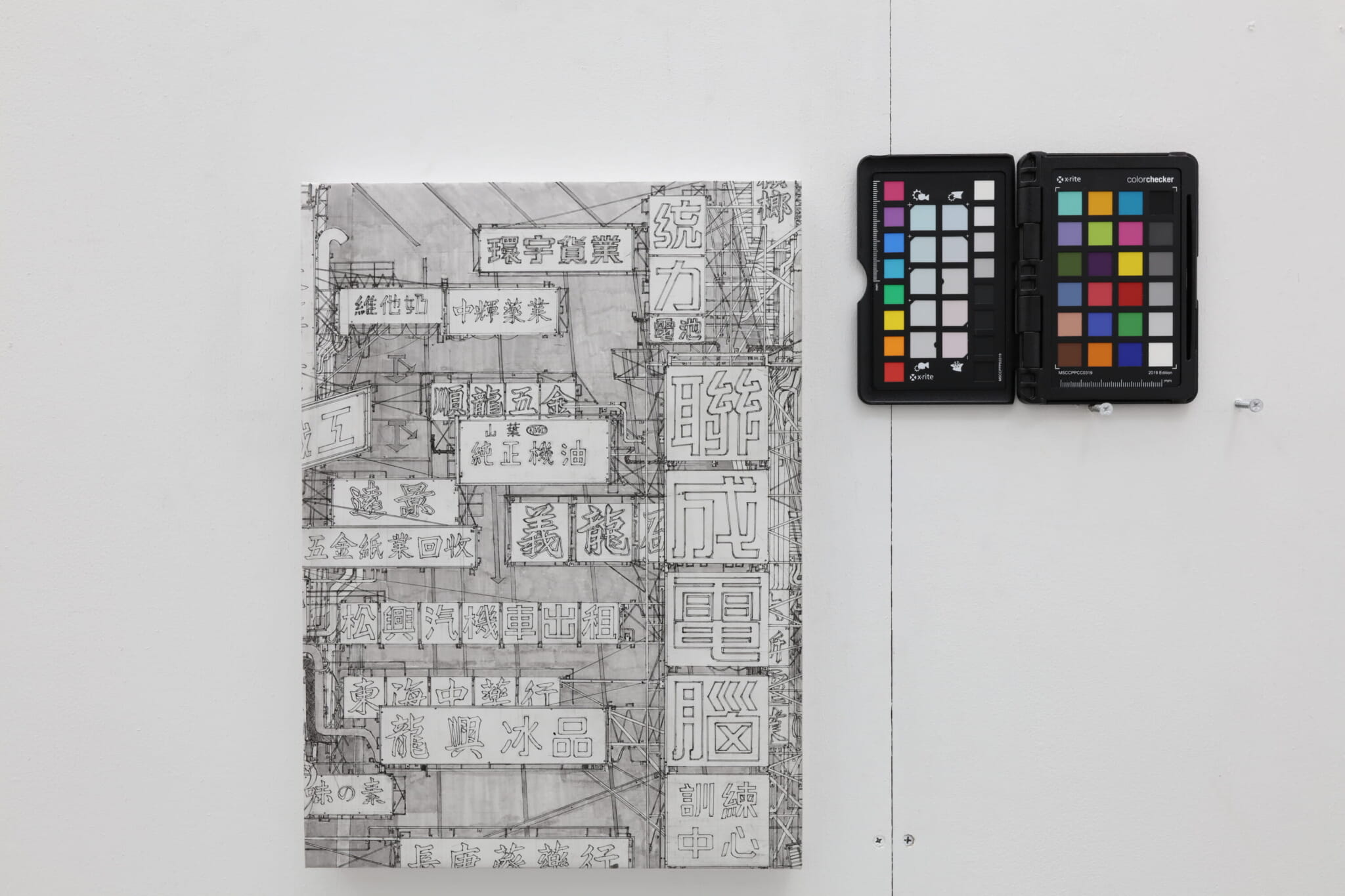

Tajima’s artworks are massive panels with dense urban cityscapes meticulously drawn in sharp black and white lines. His thousands of Instagram followers experience these works in fragments as small as the palm of their hands on their screens, but at Tajima’s exhibitions, the half-imaginary megalopolises fill up the walls and draw the viewer in, as if magical portals.

“I think in 3D, and I want to create a space within the image,” he explains.

The artwork he is currently working on measures 5 meters by 4 meters, a size Tajima considers small, wishing he could go bigger. “If you think about it, cities are much, much bigger than these panels, so I am actually making them small,” he points out.

“I think the word ‘painter’ doesn’t suit my work,” Tajima says.

“Drawing? Illustration?” I offer alternatives, but he has something else in mind.

“I build buildings inside panels and canvases,” he says and shows me the actual scaffolding he uses daily to draw his cityscapes. Aside from the pens and pencils, his tools are similar to those of construction workers, and the time to finish one artwork is not too far off from the time needed to build a skyscraper. “One of these panels takes me roughly two years to finish,” Tajima says. His schedule is simple: do art in his studio from morning to evening, 365 days a year.

The Real/Unreal Cities of the Future

Tajima’s cityscapes are reminiscent of cities we know, but they don’t exist. “Many of the kanji signs in Chinese are from real signs, though,” he shares with me. The artist draws inspiration from actual cities in China, Taiwan and Hong Kong but comes up with new buildings and compositions. He has traveled to many metropolises in mainland China, including Guangzhou, visited Hong Kong more than 10 times and Taiwan more than 30 times. He also lived in Tainan, Taiwan, for a time studying Mandarin Chinese.

“I’m still not bored. There is so much more to see, do and learn, so many local people to talk to,” Tajima says. That’s also why he’s been studying Mandarin and also picking up some Cantonese and Korean. He believes that to create art, he doesn’t need to study the art of the country he visits. Rather, he needs to communicate with its people in their words. “Words are as deep as art,” he says. “And I also just love learning languages.”

Tajima shares a fascination with Asian cities beyond Tokyo with one of his idols, Mamoru Oshii, the director of Ghost in the Shell. He was slightly surprised, however, at the exact overlap when I shared a quote from Oshii published in Kodansha’s Young Magazine in 1995: “When I was in search of an image of the future, the first thing that came to my mind was an Asian city.” Oshii was referring to Hong Kong and how he modeled the future cyberpunk city in Ghost in the Shell after it.

Even the Los Angeles of Blade Runner is awash with Asian imagery, as many visionaries have been imagining the future as multicultural. “Hong Kong is a city of immigrants from everywhere, so there is an element of internationality,” Tajima says. “It’s a blend of cultures. I think Tokyo is becoming a little bit more like Hong Kong.”

Into the Digital Rabbit Hole and Back

Another world that Tajima frequently inhabits is the digital one, where we meet for the interview. He had graciously invited me to visit him in Nara, but he expected that I wouldn’t be able to go.

He seems at peace with the fact that he rarely meets new people in person. Even when setting up his exhibitions, he’s only there for a few days. This was the case for his latest exhibition, “Beyond the Lines,” at the Roppongi Hills A/D Gallery in September 2022, which doubled as the launch of his art book of the same title.

“That’s why I like Instagram as a digital place of connection. It has opened the world to me, to talk to people I would have never otherwise met,” he says. It’s also where he showcases his process, his studio, details of his works and other facets of art that an exhibition of completed artworks doesn’t reveal.

And if limitless connections are the bright side of technology, the dark side is human replacement and the very recent and controversial AI art bulldozing over artists and the very humanity of art.

“Look, I think artificial intelligence is important and can help with many things — but not art. I don’t want to just hand over art to AI,” Tajima says. “I’m not giving it away.” He repeats this twice.

Tajima’s cityscapes are all the more beautiful because he fantasized about them, lovingly gathered memories and carefully created them over months. They matter more to both the artist and his audience. If art is one’s whole ikigai, a reason to live and dream, why outsource it?

You can find Daisuke Tajima on Instagram @tiendao06.