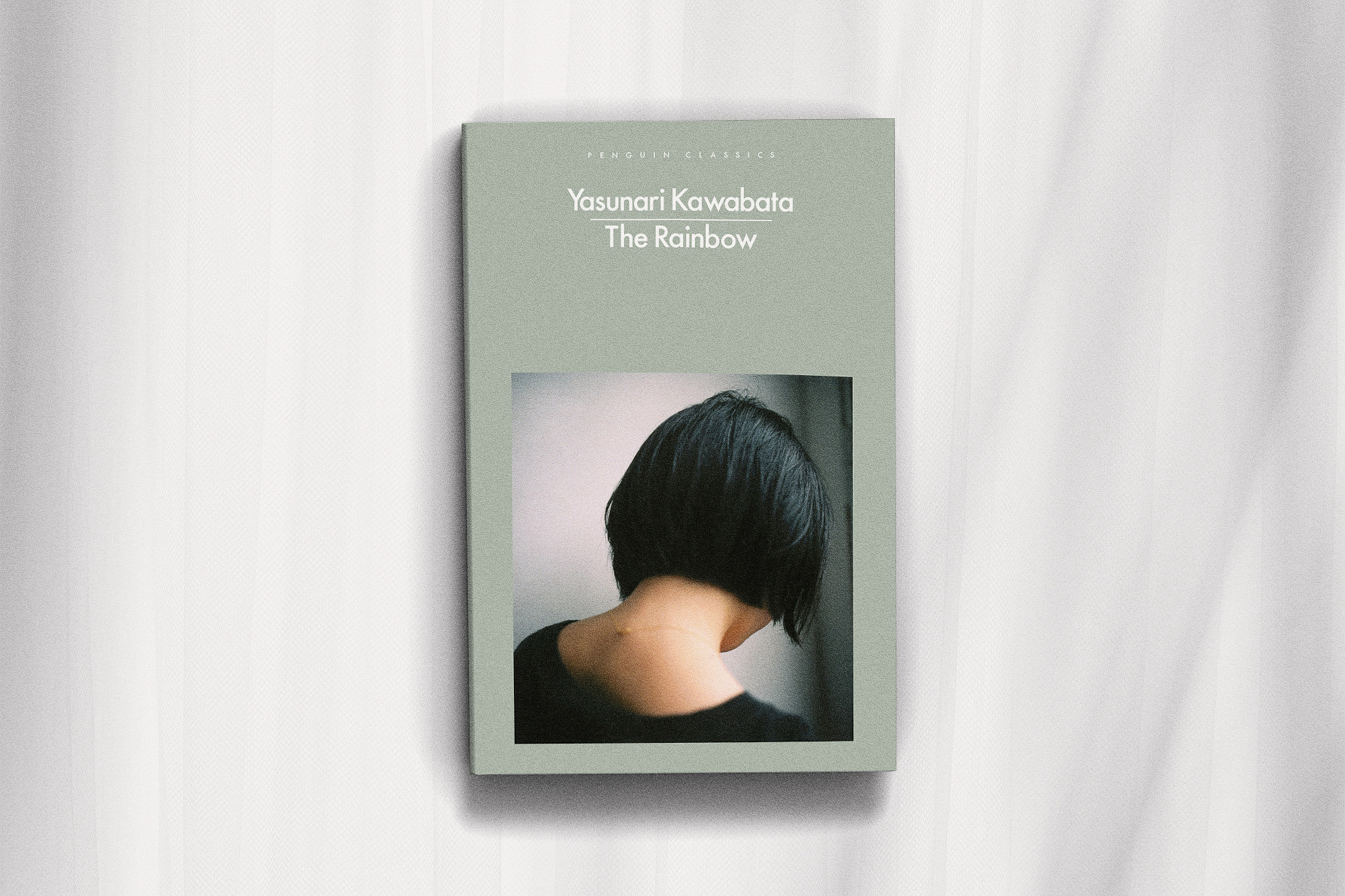

Yasunari Kawabata is well known for his exploration of beauty, nature, loneliness, death, sorrow and the transient nature of life as depicted in his Nobel Prize-winning novel Snow Country and other works. The Rainbow, newly translated into English by Haydn Trowell, and released by Penguin Publishing, is also a magnificent reflection of these themes with the added element of family bonds.

It’s a superb story focusing on two half sisters, Momoko and Asako, who are trying to make sense of their world shortly after the Second World War. They are born to the same father but have different mothers. Momoko, the cynical first-born child, is a modern girl (or moga for short) drifting from one guy to the next after her boyfriend dies in the Battle of Okinawa and her mother commits suicide. Asako is the kind-hearted second child who travels to Kyoto with her father to search for the third sibling, Wakako.

Rainbows and Beauty

Rainbows have great significance in this book. In Japanese mythology, they represent the Floating Bridge of Heaven upon which the deities, Izanami and Izanagi, are said to have stood to create the world. Buddhists also believe the rainbow is the highest state before reaching Nirvana.

“Asako saw a rainbow appear over the far shore of Lake Biwa… [She] was filled with a strange yearning to go to that country beyond the rainbow while still alive”.

Kawabata uses figurative language and poetic imagery throughout the book. On page 128, Natsuji says to Asako he would like a stone bridge to connect souls, but Asako replies:

“A bridge of stone? Wouldn’t that be awful, building a stone bridge over your heart? I would prefer a rainbow bridge.”

Beauty is a constant theme in Kawabata’s books. His appreciation of nature in all its splendor is evident throughout. His characters often comment on the pine trees or the bamboo and the various flowers and trees they see during their travels.

In The Rainbow, beauty and aesthetics feature heavily. The sisters and their father stay in ryokan inns where they eat candied plums and soybeans, eddoe root vegetables and Yuba tofu skin. They enjoy traditional multi-course dinners or kaiseki ryori. They pull back shoji room dividers and admire flowers arranged in Iga pottery as well as hanging scrolls in tokonoma alcoves.

Mizuhara, the siblings’ father, also makes comparisons between the aesthetic values of Kansai and Kanto women. He believes Kyoto and Tokyo women are inherently different and he wonders if they wear different lipstick. He’s obsessed with the way the lips and gums of Kyotoites seem to have a peach-like shade.

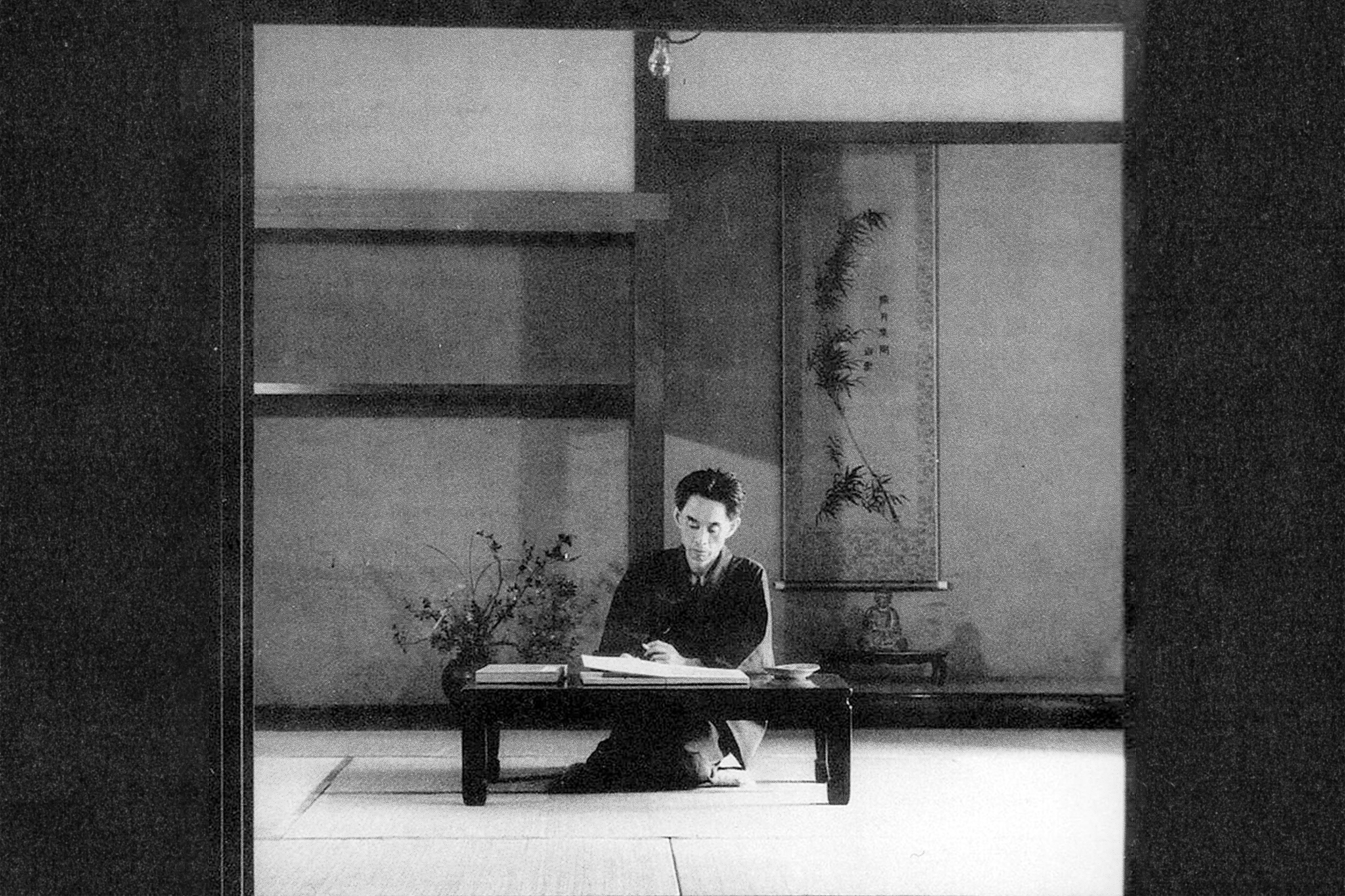

Yasunari Kawabata

In the Aftermath of the Second World War

The Second World War ravaged Japan and while in The Rainbow Kawabata doesn’t write in detail about the bombings that killed hundreds of thousands of people, he certainly makes the reader aware of the devastation felt by the Japanese people at that time.

Mizuhara is an architect that travels to Kyoto to remodel a client’s new home after his house was lost during the war. Momoko believes her father was separated from his “Kyoto woman” only because of the war. The character Aoki reflects on the war:

“I went to look at the devastation at Hiroshima and Nagasaki . . . When I walk the streets of Kyoto here, when those eyes take in all this, I shudder to think what might happen if another atomic bomb were to be dropped . . . All we can do is sit around eating boiled tofu and the like and wait quietly to meet whatever the future has in store for us.”

In a book where death is a major theme, there are also some lovely references to nature to inspire the reader: “The beauty of a single flower is enough to reawaken one’s will to live.”

Similarities Between The Rainbow and Snow Country

Fans of Kawabata’s Snow Country will appreciate the similarities between that novel and The Rainbow. Both reflect the author’s lyrical writing style and graceful prose. Wakako’s mother and half-sister are geisha, and the snow is mentioned on several occasions, but this book is set mainly in Kyoto. This is obviously a more refined area than Niigata and the hot spring location described in Kawabata’s most famous novel. The different seasons are all beautifully captured in this book, but one can see how snow still continues to play a major role in Kawabata’s heart and soul: “As he listened to the sound of the snow falling, Mizuhara felt a sudden nostalgia for the woman, still alive and well in Kyoto.”

The Japanese sensitivity to ephemera or mono no aware is also explored in the novel. The rainbow over Lake Biwa is transient in nature and Mizuhara says to Wakako’s mother Kikue: “When I’m gone, you’ll be the only woman left who remembers me.”

There is so much for readers to appreciate in this dazzling new translation, which is one of the finest examples of Kawabata’s literary brilliance.