by Fred Harris

Resurrection of the Second Best

Little does the inexperienced tenderfoot who buys a picture for pleasure or investment realize that his exposure to the art market is carefully manipulated by professional taste-makers. These people calculate plans to create false values on mediocre art. They call themselves galleries, auction houses and sometimes critics. They alter the meaning of standard terminology so that the uneducated get a false idea about the actual meaning of accepted art related terms.

To tag onto the escalation of prices of accepted world-famous paintings, the taste manipulators are offering the public a host of second-rate stuff with first-rate labels. It seems there is not enough quality art available for a thirsty public, nor are there more than a half-dozen legitimate auction houses handling established artists.

Recently in the California area there has been a rash of paintings offered for sale under the label “California Impressionists.” Through this century, especially in the 1930s, California hosted a large number of artists who came from the East Coast to lake advantage of the all-year sunshine. These were painters who worked outdoors for subject matter. The confines of an indoor studio surrounded by snow and rain was not as pleasant for the majority of “Plein-air” artist. Although many of those who fought the rough weather on the cast coast produced some fine pictures and, in fact, became, as a group, more well-known than their California cousins.

The problem is that every one is labeled an “Impressionist.” For those of us who love this period of late 19th century French art, it hurts to witness the “Impressionist” label being tossed around to anyone who threw away their tubes of brown and black paint. Granted, there were a few Americans who came back from Europe with definite Impressionist influences in their works, but the term has been so misused for material profit to cause us to mistrust anything with the label.

Another phenomenon is the appearance in major art publications of full-page color advertisements featuring the work of completely unheard-of artists who have recently died and who were lucky enough to be born in the later half of the 19th century. This 19th century birth adds a certain amount of “age” credibility to the novice collector.

I hope the reader will understand that I am not discrediting all of these artists. Some of them are damned good painters. What I am saying is that the art dealers are not being honest enough with the public. There is only a small segment of the art-buying public with the background, education, intelligence and taste to buy art for its own intrinsic value. The majority of the men-with-yen have to see the “correct” label attached to feel secure in their purchase which, in reality, becomes an attempt at investment only.

The third, and most severe, offense is the flooding of the market of scraps of paper from discarded sketchbooks of famous artists. What has occurred is that the well ran dry. There are not enough quality pictures on the marketplace and the public has been so seduced as to think that buying autographs is a substitute for buying art. A good example is the illustrated page from a famous auction house catalogue offering a few scratches by Chagall for £4,000 (see above).

If these artists knew that their personal notes and study books would be thus exposed, they would have destroyed them years ago. The equivalent would be spending money on a digital recording of a famous pianist practicing his runs on the piano.

The result of the actions of the art manipulators has been the birth of a big money-making empire. The multimillion dollar sales of the last two Van Gogh masterpieces fetched multimillion dollar fees for Sotheby’s. They received a 10% fee from the buyer, as well as the sellers. That’s 20% of big bucks. Sotheby’s is also now listed on the stock exchange. Buying their stock is probably better than buying their pictures.

Aside from the huge increase of picture sellers, we now have full time in-house art advisers for companies. There are others who offer services in art-buying advice. There are also large department stores in the museums, selling everything from scarfs, post cards, reproductions, hooks and various other gifts.

What happened to the museum which was a place to study and enjoy the beauty of the world? When I was an art student in New York in the 1950s, I was able to receive a locker in the Metropolitan Museum of Art to store my paints, canvas, etc. The museum loaned me an easel and I was allowed to copy any of the paintings on display. This was also true in the Louvre and many other museums around the world.

It’s all history now, a very important part of my world of art has passed by.

Post Script

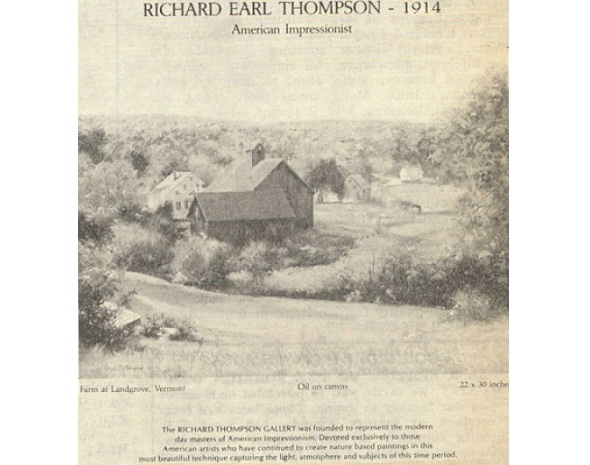

At the request of the editor, I will try to explain why the reproduction shown in the American Impressionist advertisement is not what it seems to be. The reader will have to realize that in any discussion of Impressionist art, color is the most important part of the artist’s effort. The reproduction being in black and while will confine my comments to two other areas of concern, the first being “brush technique.” The Impressionists did not separate the stroke or size of the brush from the subject. Large areas such as sky, water, fields, etc. were painted in the exact same manner, and with same size brushes as small areas, such as farm houses, people, animals, haystacks, etc.

Secondly, the Impressionists almost consistently used a very low horizon line, and quite often asymmetrical in compositions, compared to a middle of the canvas horizon or classic symmetry and golden section divisions of space.