Masako Kakizaki, from the Tsugaru region of Aomori, is a Tokyo College of Photography graduate and commercial photographer. In 2012, she launched her six-volume series Aononymous, which captures the dramatic landscapes of her home prefecture, evoking its essence without directly identifying it.

Can you describe your practice? What camera do you use?

I do commercial and creative photography. I’ve been presenting the latter as Aononymous, meaning “anonymous photographs of Aomori’s landscapes.” I work with a Hasselblad, and I think it was around 2006 to 2007 that I decided on my 6×6 format.

I stick to analog for my creative work, partially for ritualistic reasons: Analog ensures I confront the landscapes directly and decide carefully on each shutter click. Film is also essential; I use it for its rich graininess and ability to capture atmospheric details my eyes miss. I shoot with Kodak, which I’ll continue to use as long as I can get it.

How do you think being born and raised in Tohoku has influenced you?

After I moved to Tokyo, I noticed a closeness among people from Tohoku, as if we share a similar understanding of home. Maybe this feeling strengthened after the 2011 disasters, but I believe it existed before. I also think the climate of Tohoku is important. Growing up in Aomori, which even for the north gets a lot of snow, I developed an absolute, physical sense of awe and endurance in the face of nature. Things are more convenient now, but I suspect that until about 30 years ago, there was still a great disparity between life in Tohoku and Kanto.

Aononymous, the title of your most well-known series, combines “Aomori” and “Anonymous.” What do you find is the connection between them?

When I published the first book, Aononymous: Snow, I took a slightly different approach. I wanted to dispel the public’s “ethnological” image of Aomori and Tsugaru. Many photographers have come to the region, but I wanted to present another, still unknown Aomori apart from the “indigenous” and “beautiful” one captured before. I wanted to show a place that you might not recognize as Aomori if you weren’t told what it was.

How did you choose the locations?

I selected them randomly. Keeping with the anonymous theme, I hoped to do away with the proper nouns people have attached to the land. Without interference, I wanted to confront the power that has taken root and accumulated in these places where my ancestors lived.

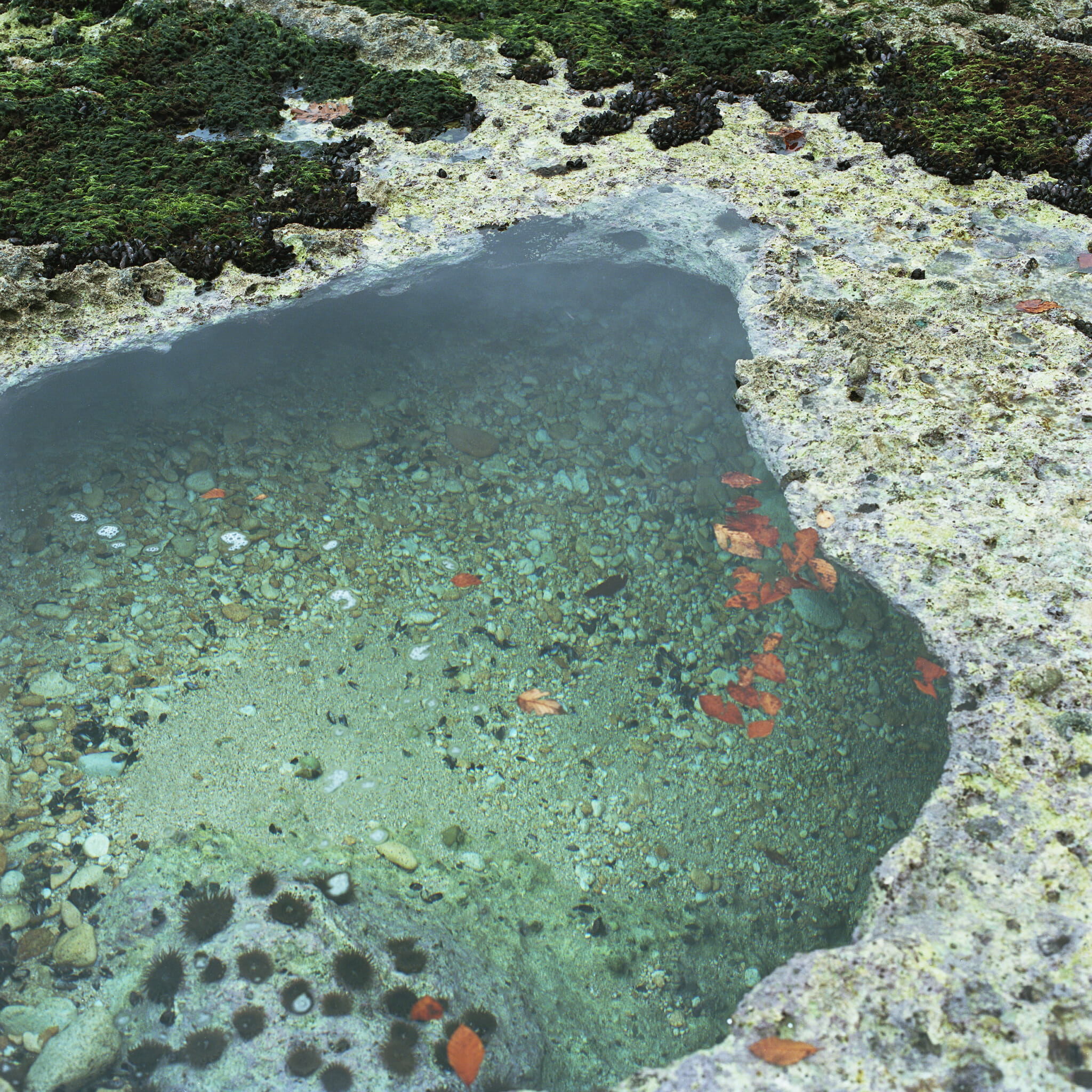

Aomori is surrounded by the Pacific Ocean, Mutsu Bay and the Sea of Japan. I was amazed at its geological diversity. I was born in Aomori city, 5 minutes from the bay, but knew only the surrounding area. When I visited the Shimokita Peninsula, I was struck by the spectacular scenery and came to the painful realization that I actually knew nothing about Aomori.

How does experiencing nature compare with photographing it?

Aononymous, Full circle, my third book, considered life cycles. Up north, plants and soil that seem to have died over winter sprout in the spring, displaying a cellular energy beyond our imagination. My aim with this work was to express the primordial forces of Aomori.

When I photograph nature, it is with a sense of surrender; I am powerless in the face of it. But when I encounter the life that springs from it, I get a feeling of serenity, as if it is permitting me to live as well. So it’s not so much a matter of “taking” a picture as respectfully being “allowed” to engage with the subject.

Your last exhibition and photobook release were in 2018. What have you been doing since?

There’s a project I’ve been working on since 2018. Until now, I’ve limited my scope to Aomori, but this is no longer the case. I thought I’d captured an “anonymous” Aomori, but before I knew it, the places seemed stuck in a framework of “being Aomori.” It was as if they lost their anonymity the more I photographed them. That’s why I decided to end the Aononymous series. I’ve realized I can engage with any place I live or happen to visit.

I’ve only recently titled my next series; I couldn’t release it until I had a certain number of photographs, and then I needed a title that would serve as a single axis for all of them. I haven’t decided when I’ll present these works, but I hope to do so when the time is right.

Find out more about Masako Kakizaki and her works.