From the Meiji Period (1868–1912) onward, the Japanese public began to be exposed to both Western art and Western artistic techniques. This led to Japanese paintings being classified as either nihonga or yoga, the former retaining traditional Japanese artistic conventions while the latter embraced innovations imported from overseas. Both styles have produced no shortage of creative triumphs, so let’s take a deeper look into what has historically separated them from one another.

Diverging Origins

The first true master of the Western style in Japan was Yuichi Takahashi, who studied under the Italian foreign advisor Antonio Fontanesi; who had been hired by the Meiji government to teach foreign art techniques. Fontanesi was instrumental in the earliest growth of yoga in the 1870s, and Takahashi created the school’s foundational works of art. Nihonga arose a little later, and as a direct reply to yoga, around the turn of the century. As a means of curtailing rapid Western influence over the country, artists began to look to Japan’s past and seek artistic continuity with it. Kakuzo Okakura, the art critic best known for being the author of The Book of Tea, was one of the chief proponents of what would become known as nihonga.

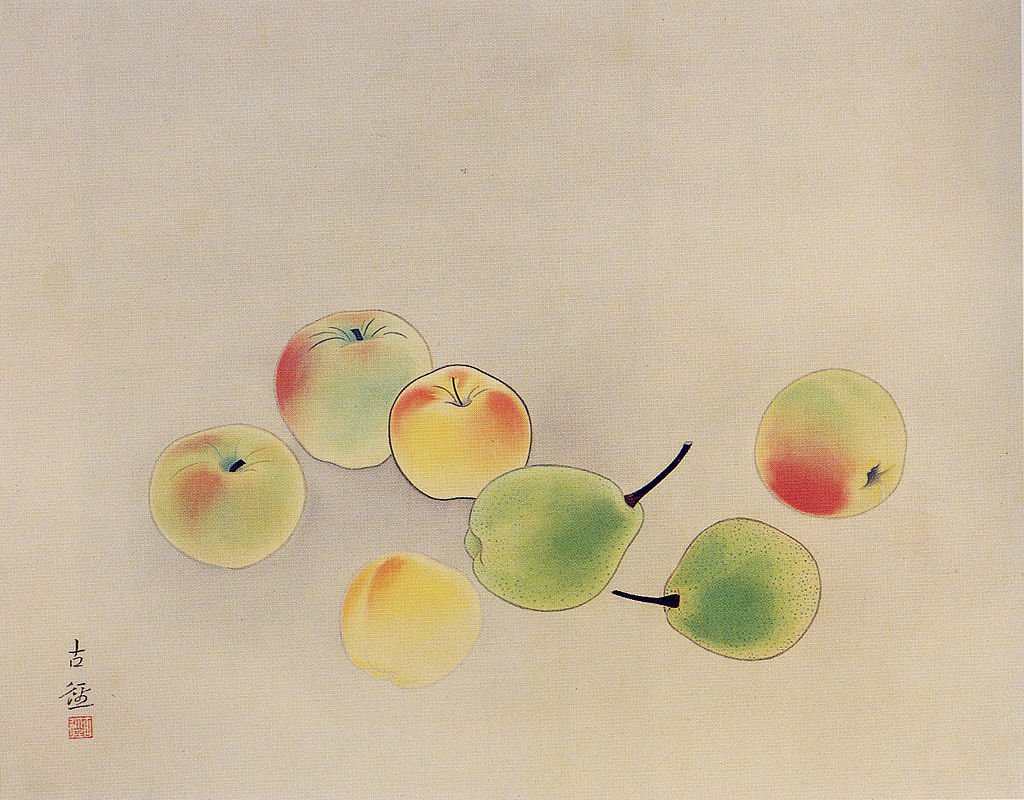

“Fruit” by Kokei Kobayashi (1910)

Washi and Silk Contrasted With Canvas

The most significant tactile difference between nihonga and yoga is the material upon which the artwork is painted. Yoga is generally oil-on-canvas, which has been the dominant method of painting in Europe and North America for centuries. Other European conventions, such as pastels and watercolors, are also considered to represent yoga.

In contrast, nihonga is painted on the traditional Japanese paper known as washi, which is intricately crafted by hand using locally sourced fibers. If it’s not on washi, nihonga may also be painted on colorful Japanese silk cloth.

Both materials allow for the absorption of colors in a soft and elegant manner that is characteristic of the kind of images we associate with Japanese painting. Nihonga were originally produced for scrolls, sliding doors and folding screens; the kind of objects that we traditionally associate with Japan. With the passage of time, creating them for the purpose of framing became more commonplace.

The Value of Simplicity

Nihonga works tend to contain a considerable amount of empty space and are typically less “busy” than their Western-inspired counterparts. This notion of negative space is summed up in the Japanese idea of ma, which emphasizes and appreciates emptiness in art. Both the Kano and Rinpa schools of painting, which were artistically dominant prior to Japan’s opening up, availed of this appreciation of the void between objects. Nihonga can be seen as a proud continuation of this subtle and delicate approach to viewing the world.

“Lake Shore” by Kuroda Seiki (1897)

The free exchange of ideas and techniques between Japan and the West allowed yoga painters to be exposed to a variety of artistic movements that originated on the other side of the world. These included Cubism, Naturalism, Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, all of which impacted the development of Western-style paintings in Japan.

Seiki Kuroda, regarded as one of the most significant figures in the yoga movement, was especially influenced by French Impressionism as a result of an extensive stay in Paris. “Lake Shore,” which depicts a young woman at the shore of a lake, is emblematic of the Western-modeled Japanese works of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Nihonga meanwhile remained steadfast in its overall rejection of these international movements, opting instead to stick to established local conventions.

A National Backdrop and Ethos

Nihonga artists deliberately infused their output with distinctly Japanese attributes in both form and substance, from depicting cultural staples to showcasing national flora and fauna. Shoen Uemura, one of the most acclaimed female artists of nihonga, was particularly noted for her exquisite bijin-ga, depictions of beautiful women clad in traditional Japanese garb. Her most famous work, “Noh Dance Prelude,” was painted in 1936 and was the first work by a woman to be distinguished as an Important Cultural Property by the Japanese government. Uemura’s works, and their nationalistic trappings, held propaganda value during the Pacific War to the point where she visited China during the height of hostilities to give public morale a boost. The globally-minded artists of yoga were unsurprisingly less popular during this period.

“Ginza” by Ryusei Kishida (1911)

Differences and Similarities Today

The line between nihonga and yoga may often become blurred, especially in more recent years, but the concept of a distinction between the two often remains entrenched within Japanese art. The Yamatane Museum of Art in Hiroo has positioned itself as Tokyo’s foremost museum focusing on historic and contemporary nihonga, while the National Museum of Western Art in Ueno Park holds a formidable collection of some of the most important works of yoga. Anyone with even the slightest interest in the world of Japanese artistic expression would benefit from visiting both and seeing how they complement each other.