A pampered childhood, a notorious obsession with her father and a trilogy of novels that kickstarted the boys’ love genre: Mari Mori’s legacy is as fascinating as it is scandalous. Active throughout the 1960s and ’70s, Mori wrote passionate, homoerotic romances about elegant men living elegant lives. Her bold fantasies have captured women’s imaginations for decades, launching a genre that remains popular to this day.

Less Than Humble Beginnings

Mori was born in 1903, the eldest daughter of Lieutenant-General Ogai Mori and his second wife, Shige. Her father was a celebrated novelist and translator, known as one of modern Japan’s ‘founding fathers’ for his important contributions to literature, medicine, and philosophy. He doted heavily on all of his children, but his bond with Mari was especially strong. She idolized him her entire life, leading some to dub her the ‘Japanese Electra.’

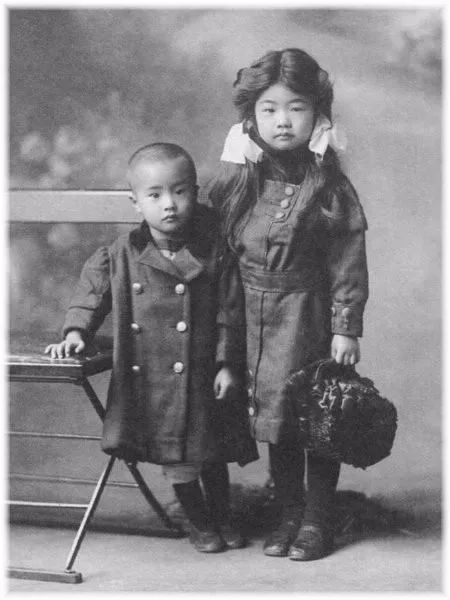

Children of Japanese writer Ogai Mori. L-R: Rui and Mari.

When Mori was just 16, her father arranged for her to marry Tamaki Yamada, a scholar from a wealthy family. The couple moved to Europe soon after. Unfortunately, Ogai Mori died while his daughter was still overseas. Mori never recovered emotionally from her father’s death. Her marriage soured as a result. In her essay “Thorn” (“Toge”), she contrasts Yamada unfavorably with her father, likening her grief to the trauma caused by the loss of a lover.

Mori divorced in 1927, leaving her two children, Jacques and Toru, in the Yamada family’s care; she wouldn’t reunite with them until two decades later. Her second marriage to a professor at Tohoku Imperial University ended similarly after less than a year. She later said that she couldn’t stand living in Sendai “without Ginza or Mitsukoshi nearby.”

Mori struggled to maintain her former standard of living after her two divorces. Raised in an affluent household, she was notoriously averse to doing chores. She defined her approach to life as “luxurious poverty” (zeitaku binbou), spending much of her meager budget on foreign jams and chocolates.

Television personality Tetsuko Kuroyanagi once described Mori’s apartment as being full of hoarded magazines and cockroaches. For many years, she lived off the royalties earned from her father’s writing. When those copyrights expired, she was forced to find another source of income and turned to writing.

From Ogai’s Hat to Mari’s Forest

At age 54, Mori published a collection of essays about her late father entitled My Father’s Hat (Chichi no Boushi), which won her the Japan Essayist Club Award. Much of her early success rode on her father’s fame and the unique perspective that she had as his daughter. In the following years, however, she found her footing as a fiction author.

She published her first novel, The Lovers’ Forest (Koibito-tachi no Mori), in 1961. The first of a spiritual trilogy, this novel explores the tragic relationship between Gidou, a professor of French literature, and his beautiful young student Paolo. Their fairy-tale romance ends when Gidou is slain by a former lover.

The intricate style of The Lovers’ Forest garnered praise from authors like Yukio Mishima, who spoke highly of Mori’s penchant for poetic language. The novel is indeed filled with lavish descriptions of decadent foods and pink Rolls-Royces, an escapist fantasy of unattainable excess. For Mori, it served as another form of escape; the character of Gidou was modeled after her father, as were many of her protagonists. Writing was partly her way of bringing her father back to life.

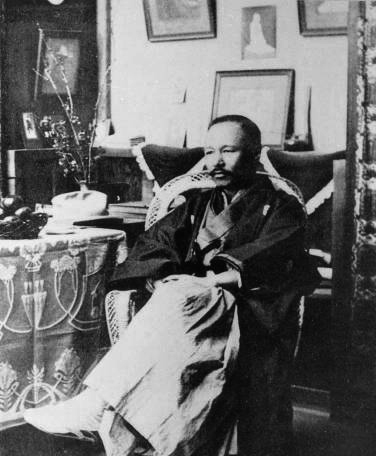

Ogai Mori visits the atelier of Kozaburo Takeishi in Sugamo.

Mori’s novels also became popular among young women, many of whom were becoming disillusioned with society’s promises of marriage and heteronormative adulthood. Her stories resonated with them because she projected women’s fantasies onto men’s bodies. The Lovers’ Forest and its ilk offered a refuge from misogyny, a place for female readers to experiment with being agents of desire rather than its objects.

A Genre is Born

Mori’s work inspired many younger women to pen their own fiction centered on these homoerotic relationships. The new genre they created took many names, eventually coming to be known as “boys’ love,” or simply “BL.” Although Mori herself was reluctant to label her own work as boys’ love, she was one of the few literary women producing such material in the ’60s, and thus helped blaze a trail for the next generation.

It wasn’t until the late ’70s that artists like Moto Hagio and Keiko Takemiya brought boys’ love narratives to the world of shojo manga. The first magazine solely dedicated to this content, June, began publication around the same time. Boys’ love author Kaoru Kurimoto, who made her debut nearly two decades after The Lovers’ Forest came out, has specifically cited Mori’s influence not only on her own work, but on the genre as a whole.

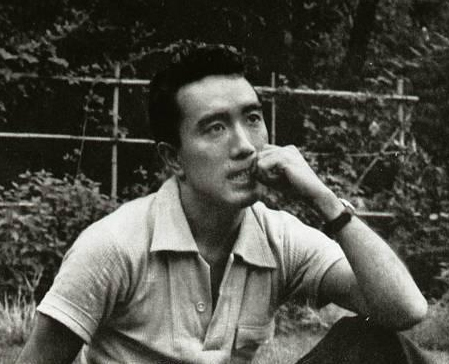

Yukio Mishima

Despite the popularity of boys’ love, the genre has also come under fire for failing to represent gay men’s lived experiences and the realities of homophobia. Mori and her successors worked in virtual isolation from Japan’s gay male community, often mimicking heterosexual dynamics; for example, one partner in each pairing was almost always portrayed as effeminate and lacking agency, taking on the conventional ‘woman’s role’. These unrealistic portrayals prompted activist Masaki Sato to write an open letter criticizing Boys’ Love for co-opting the struggles that gay men face in society, kicking off decades of debates over the politics of identity and desire that still haven’t been settled.

Lasting Legacies

Since then, boys’ love has enjoyed a boom Mori could have never imagined, gaining great popularity in countries like China, Thailand and the Philippines. Many contemporary BL authors are pushing back against the damaging clichés perpetuated by their predecessors. The genre is more diverse than ever before and boys’ love has increasingly been credited with helping readers make sense of their own gender and sexual identities.

In 1987, Mori passed away alone in her apartment from natural causes. A troubled woman who never found a way to revive the magic of her childhood — or her father — Mori might be glad to know she has encouraged so many kindred spirits. Whether her novels are mere flights of fancy or deeper meditations on unfulfilled desire, Mori’s legacy lives on in the hearts of everyone she has inspired.

Author’s note: Although very few of Mori’s works have been translated into English, you can find Thorn (Trans. Angela Yiu) in More Stories by Japanese Women Writers: An Anthology, and The Lover’s Forest in Fantasies of Cross-Dressing: Japanese Women Write Male-Male Erotica by Kazumi Nagaike.