Women in Japan face regular labeling by foreign media, often being described with words such as polite, reserved and submissive. But countless Japanese women are proving these labels to be wrong. So how is Japan, one of the most highly educated countries and largest economies, still being perceived as having such an imbalanced stance on gender equality?

First, we should consider how society’s expectations for men and women have been documented in popular media around the world for centuries. In Japan, one of the earliest forms of this type of media was found in ukiyo-e – an art movement during the Edo Period (1603-1867) that encouraged artists to record daily life in Japan. New printing techniques at the time allowed the images of ukiyo-e to be mass produced and become a form of popular media.

By looking at the images of ukiyo-e and considering their context, we can understand how the stereotypes of Japanese femininity evolved.

Yoshiwara Courtesans: A New Mirror Comparing the Calligraphy of Beauties, Kitao Masanobu (Santō Kyōden); Japanese, 1784

Ukiyo-e’s Courtesan Celebrities

Many of the women featured in ukiyo-e were courtesans from the pleasure quarters, but they meant more to society than sex. These were capable women who were highly educated and provided clients with skilled entertainment and sophisticated conversation. The courtesans were able to experience a celebrity status within society and wealthy women even chose to follow their fashions.

The renowned skills of the courtesans are celebrated in a print by Kitao Masanobu (pictured above). The largest standing figure, plus the woman to the right of her, are courtesans (identified as such by their hairstyles) and the walls of the room are decorated with examples of their calligraphy. This image celebrates the artistry and sophistication of the two women while clearly showing their roles as courtesans.

Experiencing such a respected celebrity status in society while being a woman working in the sex industry would have been impossible in Western culture during this era. Prostitutes have regularly been muses in European and American art however their profession has been seldom obvious and, rarer still, celebrated by the art produced. While we each have our opinions as to what we consider to be immoral, our culture plays a large role in defining this for us.

In many Western cultures sexual indulgence has been historically labeled as something unclean or immoral. This would have made it impossible to be considered a respected and sophisticated member of society while openly identifying as a prostitute.

Meanwhile in Edo-era Japan, men and women freely indulged in sexual pleasure, understanding it to be a natural celebration and appreciation of the world around them. This difference in perception is what allowed courtesans to be seen as respectable celebrities within Japanese culture.

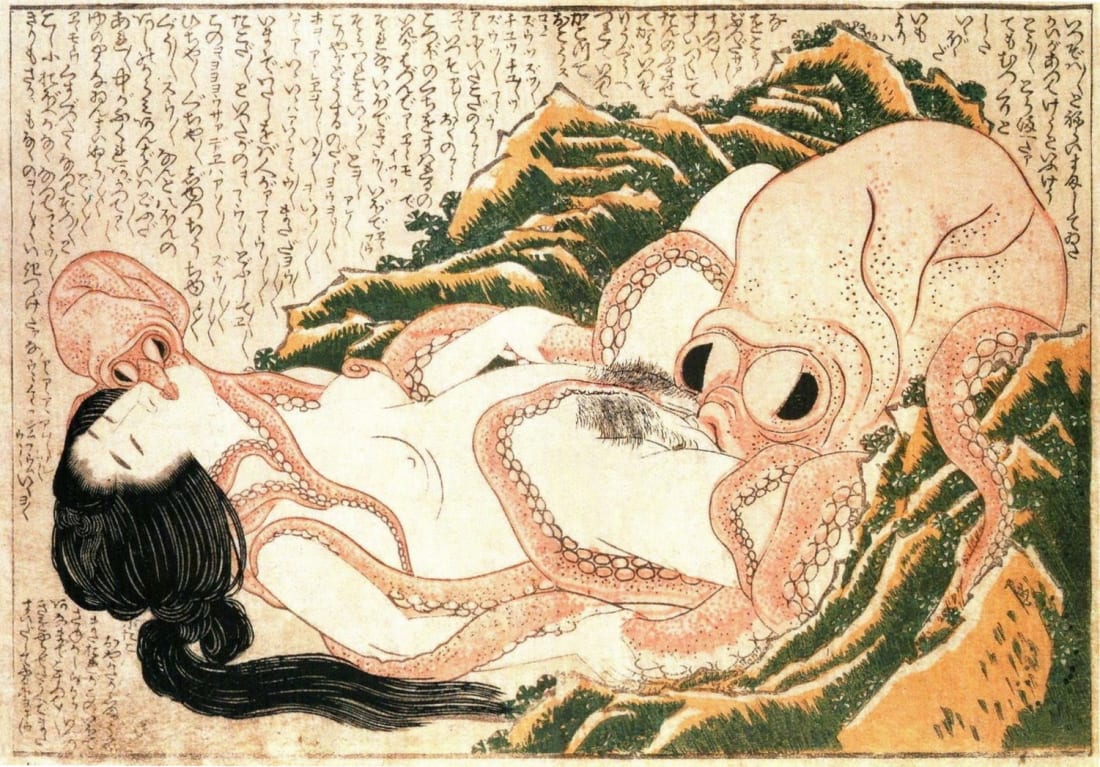

The Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife, Hokusai, 1814

Japan’s Edo-Period Acceptance of Sexual Pleasure

Japan’s acceptance of sexual pleasure as an enjoyable fact of life meant many artists were also producing erotic prints. These images were incredibly detailed and would have been scandalous if displayed in Europe at the same time.

In the above print by Hokusai, one of the first things we notice is the unashamedly large genitalia. In Japanese art we can see an equal representation of women and men, but female genitalia have rarely appeared in Western art history – which is especially surprising given the popularity of the female nude.

This is because the women of Western art have been regularly subjected to the male gaze and are shown for the pleasure of the audience. They often have direct eye contact with the viewer, and their body is positioned towards them, submitting to their desires while covering their genitalia, which were considered too ugly to show in detail.

In Hokusai’s print we can also see the woman’s eyes are closed – this is perhaps one of the most significant elements of the image. The woman is not here for us and has not even acknowledged our presence. We are watching her in a moment of selfish pleasure which gives her far more power than the majority of women depicted in Western art.

How Westernization Shaped Today’s Preconceptions

Of course, not all women are represented by these images of ukiyo-e. Another female ideal did exist in Edo-period Japan – that which forms today’s stereotype – the modest wife who was devoted to her children and husband while maintaining the home.

But why, even though we have identified the existence of two different feminine ideals, is the more modest one the basis of today’s preconceptions of the Japanese woman?

During the Edo period, Japan isolated itself from the rest of the world, and its culture and beliefs developed in ways that can be considered uniquely Japanese. After the Edo period, Japan chose to reconnect with the wider world. During its isolation Japan had experienced dramatic cultural and artistic developments. However its technological advancements and military power had fallen behind.

A desire to modernize and connect with the wider world, plus the Allied occupation after World War II, saw Japan undergo an intense period of Westernization. Part of this process was needing to be seen by Western societies as a civilized and respectable culture. This process of adapting to another culture’s values brought an end to one of Japan’s feminine ideals – that of the courtesan – because of how Western culture historically links sexual indulgence with vulgarity.

While this gender ideal has faded from modern Japanese culture because of links to the sex trade, she represents more than prostitution. The courtesan was famed for her intellect, skills and accomplishments, while being celebrated for her femininity. This is a gender ideal that offers a contemporary and universally positive image of womanhood that shouldn’t be forgotten just because its historical context challenges the beliefs of other cultures.

Today, as always, many Japanese women are proving the singular female gender stereotype to be false, and it’s time the rest of the world recognized the diversity of feminine roles and characteristics celebrated within Japanese culture.