They are crimes that shocked the nation and bamboozled the police. Fifty years on from the 300 Million Yen Robbery, the most famous bank heist in Japanese history, TW looks back at some high-profile cases that remain a mystery today. We begin with the murder of a national hero.

The Omi-ya Incident

An iconic figure in Japanese history, Sakamoto Ryoma is best remembered as the man who brokered a peace deal between the warring provinces of Satsuma (Kagoshima Prefecture) and Choshu (Yamaguchi Prefecture), helping them conquer the Shogunate.

Yet, as Ryoma’s influence grew so did his enemies, and on December 10, 1867, just a month after the restoration of imperial power, he was assassinated at Kyoto’s Omi-ya (a soy sauce shop and inn) along with his ex-sumo wrestler bodyguard Tokichi Yamada, and friend Nakaoka Shintaro. The bodyguard was the first to be slain after answering the door to a guest who wished to see Ryoma. The assassins then charged past the wrestler to the upper floor where they attacked Ryoma and Shintaro. The former died on the night while Shintaro followed two days later. Though able to explain what happened, he couldn’t identify the perpetrators.

Sakamoto Ryoma

A few months later, chief suspect Kondo Isami was executed. He was the leader of the Shinsengumi, a Kyoto-based special police force protecting the Shogunate. In 1870, Imai Noburo, a former member of a rival pro-Shogun police force called the Mimawarigumi, claimed to have murdered Ryoma with other members of his group. However, there are doubts as to the veracity of his confession. The identity of the killer has never been proven and continues to be debated by historians today.

The Teigin Case

More than three decades after being sentenced to hang, 95-year-old prisoner Sadamichi Hirasawa died from pneumonia in 1987. Convicted of mass poisoning and robbery, the tempera painter spent 32 years on death row. None of the justice ministers during that period were prepared to sign his death warrant due to widespread doubt over his guilt.

The crime Hirasawa was accused of committing occurred around closing time at the Teikoku Bank (known as Teigin) on January 26, 1948. A man claiming to be an epidemiologist presented employees with a business card identifying himself as Doctor Shigeru Matsui. He said he was sent by the US Occupation authorities because of a dysentery outbreak in the neighborhood. The 16 people present were all given supposed antidotes, and 12 died. The poisoner then disappeared with around ¥160,000, strangely leaving behind ¥180,000.

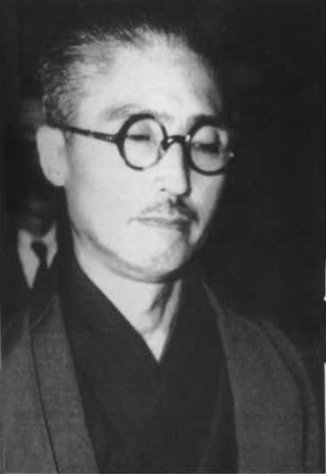

Sadamichi Hirasawa

The real Dr Matsui had an alibi, so the police tracked down Hirasawa, who had received a business card from the doctor months earlier. When the police asked him to show them the card, he claimed he had lost it, leading the police to suspect him as being the poisoner impersonating Dr Matsui. Despite a lack of concrete evidence, the artist was interrogated and reportedly tortured for weeks before eventually confessing. His defense claimed he suffered from the amnestic disorder Korsakoff psychosis, making his admission of guilt unreliable.

Many people felt Hirasawa was a fall guy, sacrificed to protect researchers from Japan’s covert wartime chemical and biological weapon division, Unit 731. They were secretly given immunity by the US after WWII in exchange for data gathered through human experimentation. David Peace, author of Occupied City, a story based on the Teigin Incident, believes “this kind of crime could only have occurred during the Occupation.” He started the book hoping to “solve the crime,” but in the end, the only thing he was sure of was Hirasawa’s innocence.

The 300 Million Yen Robbery

On a rainy morning 50 years ago, a lone robber impersonating a police officer convinced four bank employees transporting bonuses for Toshiba workers that their cash-laden vehicle was about to blow. As they fled, he got behind the wheel and drove off with almost ¥300-million. At the time it was the biggest bank heist in the country’s history.

In the weeks leading up to the incident, a series of bomb threats had been sent to the Nihon Shintaku Bank manager. Staff had been informed about this, so when the uniform-clad robber told the men in the armored car that their boss’s house had been blown up, they believed him. He then warned them to retreat as dynamite had been planted in their vehicle.

The criminal went under the van to investigate while secretly igniting a warning flare. With smoke rising, he yelled to the men to take cover. They headed towards Fuchu Prison, the nearest building. It was the perfect opportunity for the thief to escape. Covering his tracks, the criminal abandoned the van, transporting the loot from one stolen car to another. He left 120 pieces of evidence at the scene, mostly everyday items to confuse the cops.

An exhaustive and ultimately fruitless investigation included a list of 110,000 suspects. Two police officers died from being overworked. The efforts were all in vain as the statute of limitations expired in December 1975. Since 1998 the criminal has been free to tell his story without fear of legal repercussions but has yet to come forward.

The Monster with 21 Faces

It began with the kidnapping of Katsuhisa Ezaki, president of famed snack maker Ezaki Glico. A ¥1 billion (plus 100kg in gold bullion) ransom demand was issued for the tycoon after he was dragged from his bathroom by two masked assailants on March 18, 1984. Ezaki escaped three days later, however, during the following month, three Glico vans were set ablaze and a threatening note with a jug of hydraulic acid was left for the company.

Shelves then had to be cleared following a letter warning Glico about cyanide-laced candy that had been distributed to its stores. The note was signed by “Kaijin Nijuichi Menso” (the Monster with 21 Faces), named after a villainous shapeshifting thief in Edogawa Rampo’s popular detective novels.

“It’s a crazy story full of mystery that far surpasses any piece of fiction I could’ve come up with”

Taking great joy in avoiding capture, the “monster” mocked the police for their inability to arrest the culprit(s). The extortion campaign against Glico eventually ended on June 26 with a letter informing the food giant that it had been forgiven. That wasn’t the end of it, though. The next targets included Marudai Ham, House Foods Corporation, and most notably Japan’s largest confectioner Morinaga. Letters were sent to press agencies informing Japanese mothers that Morinaga sweets had been spiked with cyanide. The poison was discovered in 21 candy bars.

A suspicious-looking “fox-eyed man” twice evaded capture after appearing at staged ransom collections. Activist Miyazaki Manabu matched the description but had watertight alibis. A final letter in August 1985 confirmed that the reign of terror was over following the suicide of Shiga Prefecture’s police superintendent Shoji Yamamoto. The case officially closed in February 2000, with no arrests having been made.

Director Michael Welborn based his first feature-length film, The Monster with 21 Faces, on the Glico Morinaga Case. “It’s a crazy story full of mystery that far surpasses any piece of fiction I could’ve come up with,” the filmmaker told TW.

The Setagaya Family Murder

A devastating crime, several clues, and an extensive manhunt involving thousands of police officers, yet 18 years on from the brutal murder of the Miyazawa family and the killer still hasn’t been caught.

Mikio Miyazawa, 44, his wife Yasuko, 41, and their eight-year-old daughter Niina were stabbed to death while six-year-old son Rei died from strangulation at their family home in Setagaya, Tokyo on December 30, 2000. Bizarrely, the criminal then spent several hours in the house. He took a nap on the sofa, used the computer, drank barley tea, ate popsicles, and used the toilet. Unflushed feces found in the upstairs bathroom contained traces of sesame seeds and string beans. Before leaving, he got changed. The clothes the killer wore were neatly folded and left at the scene along with the murder weapons and his blood.

Setagaya Family Murder House

DNA analysis revealed that he was mixed-race with an East-Asian father and a mother of Southern European descent. Sand found in his hip bag was traced back to the Edwards Air Force Base in California and a skate park in Japan (Mikio had previously been seen arguing with skateboarders near his home).

Despite all this evidence, the criminal continues to escape justice. There’s a reward of ¥20-million for information leading to an arrest. The number to call is 03-3482-0110.