As more women around the world are going public about the sexual assault they’ve endured, journalist Shiori Ito has become one of the few brave voices to speak out from Japan.

After accusing a former Washington bureau chief from Tokyo Broadcasting System (TBS) of quasi-rape (a term in Japanese law that refers to having sex with a woman by taking advantage of loss of consciousness or inability to resist), Shiori Ito was told the case wasn’t worth pursuing. Convictions were rare and speaking out about it could damage not only her own career, but also the lives of members of her family. The easier option would have been to drop the claim, take the compensation money and never speak about what happened again. For the young freelance journalist, however, that simply wasn’t an option.

Shiori Ito Breaks Silence About Sexual Violence in Japan

“People have told me how brave I’ve been talking about this openly, but it’s something I felt I had to do, and this was the only option I had left,” Ito recently told Weekender. “It’s killing me sitting here having to relive the whole experience, but staying quiet and being patient isn’t going to help. I’m not trying to sling mud at the perpetrator. We need to look at the bigger picture. Sexual violence is all around us, yet remains a taboo topic in this country. After 110 years, finally some changes were made to the rape laws, which was a start, but more changes are needed and the reality is that until we engage in more open dialogue about this issue, no significant progress will be made. As a journalist, this is a drum I’ve been banging for a while, so it was imperative that I came forward and spoke about my own ordeal.”

Facing a packed press room at the Tokyo District Court in Tokyo last May, Ito said she met up with influential TBS journalist Noriyuki Yamaguchi at a sushi restaurant on April 3, 2015 to speak about a job opportunity. She claims that although she has no evidence of a date-rape drug being used, he dragged her to a hotel room and raped her. Ito later filed a criminal complaint at Takanawa Police Station (despite being discouraged from doing so). The investigator collected CCTV footage of her being carried into the hotel, DNA from her underwear and testimonies of the taxi driver and bellman.

In June 2015, an arrest warrant was issued for Yamaguchi who was due to fly in to Japan from the States. Upon his arrival at Narita Airport, the police were ready to take him into custody, but at the last minute the decision was dramatically overturned by Itaru Nakamura, the then head of the criminal investigation division at the Tokyo Metropolitan Police Department. He admitted to the warrant suspension in an interview with magazine Shukan Shincho, but has yet to follow up as to the reason, despite Ito’s several attempts to elicit a response. Nakamura happens to be a former secretary of cabinet minister Yoshihide Suga, a confidant of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe. Yamaguchi, who is also known to have close ties with the PM, strenuously denied the allegation against him, claiming that Ito simply drank too much.

“My reputation was damaged by the media treating me as if I was a criminal,” Yamaguchi said via his lawyer. “In the course of this investigation, I’ve never been found to have done something against the law. With the decision not to prosecute, this case has come to a conclusion.”

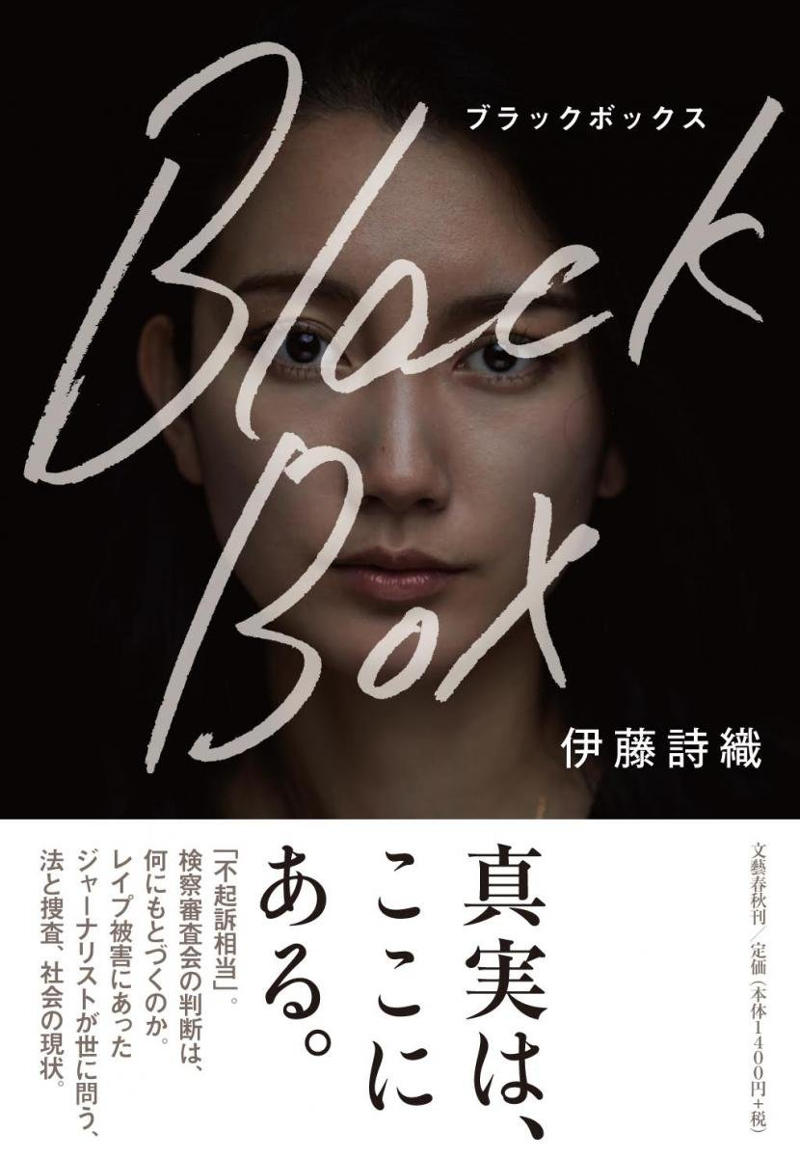

Not for Ito it hasn’t. Refusing to slip away quietly, she gave a detailed account of the incident in her recently released book, Black Box, and at the end of last year filed a civil lawsuit against Yamaguchi.

The 28-year-old journalist is one of a number of people around the globe who came forward in 2017 to speak out about sexual assault and harassment in the wake of the Harvey Weinstein exposé. Giving rise to the #MeToo movement, this group of people was collectively referred to as The Silence Breakers and named as Time magazine’s “Person of the Year.”

Attacks on Ito a Warning to Other Women Against Speaking Out

For Ito, breaking the silence must have been all the more daunting given how rare it is for people to go public with accusations of rape in Japan. Since the press conference last spring, there’s been a mixed response from the public. Messages of support came flooding in, but there was also much criticism. A strong, articulate woman who came across as composed in front of the media, she didn’t appear like a stereotypical victim, and suffered a backlash as a result.

“The negative messages have probably outweighed the positive ones,” Ito says matter-of-factly. “The worst comments seemed to come from older women who for decades have lived in a male-dominated world. They felt I wasn’t behaving the way a Japanese lady should. I was told it was wrong to have the top button of my shirt undone during the press conference. If I had cried they would have been more sympathetic. One person found a picture on my former co-worker’s Instagram page of me smiling two months after the incident and asserted that I couldn’t possibly be a genuine victim. I received death threats and some odd things happened around my apartment, so I decided to move in to my friend’s place for a while. It was tough, but I couldn’t let it defeat me as then I would have become an example of why people shouldn’t speak out about these crimes and that’s the exact opposite of my intention.”

By making her case public, Ito is hoping to encourage more victims of sex crimes in Japan to open up about their experiences, though she feels societal expectations may continue to hold them back.

“As a nation we tend to keep things in due to our upbringing,” Ito says. “Don’t get me wrong, sexual abuse is an uncomfortable topic for anyone, anywhere in the world, to address publicly. Even an outspoken star like Lady Gaga kept the fact that she was raped secret for seven years. But in Japan I believe there’s an even greater reluctance to speak out because of the stigma attached to sex. We never discuss what’s right or wrong. I remember at elementary school being sent into a different room from the boys for sex education. We were taught how to make a baby and the danger of sexually transmitted diseases, yet there was nothing about the potential threat of sexual violence, and I still didn’t really know about it at high school. After being raped I was unsure what to do as I’d never been told anything.”

Nevertheless, She Persisted

Frightened and confused, Ito struggled to find a hospital that provided rape kits. Hoping for some advice over the phone, she called a rape crisis center, but was told to go in for an interview. The police were even less accommodating, initially telling her it wasn’t worth pressing charges. She eventually convinced them, but was then forced to retell her story repeatedly for the next four months.

The worst comments seemed to come from older women who for decades have lived in a male-dominated world. They felt I wasn’t behaving the way a Japanese lady should.

“It’s easy to understand why so few people report these crimes,” Ito says. “According to a 2014 survey by the Cabinet, just 4.3 percent of women who were victims of a sexual crime consulted the police. That number isn’t going to significantly increase simply by making modifications to the justice system. We need to go deeper than that and look at society as a whole, from the way we’re educated to the way we treat and respond to rape survivors. More than anything, we must draw inspiration from what’s happening in Hollywood and around the world with the #MeToo movement, and start talking openly about sexual violence. The media in Japan is finally beginning to focus on what needs to be done rather than just pointing fingers; however, we’re still far behind most countries in Europe and North America when it comes to this issue.”

With our interview drawing to a close, Ito’s eyes start to well up. Usually the one asking the questions, she admits to finding it tough being on the other side of the fence as journalists dig deep to find out about her personal history. Now working in London, she’s managed to move on with her life, but still thinks about the incident every day.

“No matter how much I’d like to, I can’t bury what happened,” Ito says. “I’ve found it difficult to form relationships, which has left me quite isolated. I feel most sorry for my family, who’ve suffered badly. My younger sister was really hurt and afraid that my decision to speak publicly would stop her from getting a job. We finally managed to talk after seven months. She now understands the importance of standing up to stop sexual violence because anyone can be a victim.”

Black Box by Shiori Ito is available (in Japanese) on Amazon for about ¥1,500.

Main Image by Tsutomu Harigaya