A conversation with the man that goes beyond the headlines.

At first thought, tetra-amelia syndrome would seem like a prison sentence. Those born with the congenital condition have neither arms nor legs, and many of them die at an early age. Survivors who make it to adulthood often suffer from a host of painful complications to go along with their immobility. In previous generations, tetra-amelia survivors might have led cloistered lives or joined traveling circuses in order to get by, and while the prognosis for those living with the syndrome might be better than before, it would be hard to expect them to lead lives like the rest of us.

Someone forgot to tell this to Hirotada Ototake.

As the journalist, author, and educator explains, though, he wouldn’t have listened even if someone had told him what his limitations were supposed to be: “I have never been good at doing the same thing that everyone else did.” Just shy of his 40th birthday, Ototake has spent his life challenging expectations of what the disabled can achieve, and at the time of this interview, he was considering a run for political office – however, these plans were brought to an end by a personal scandal.

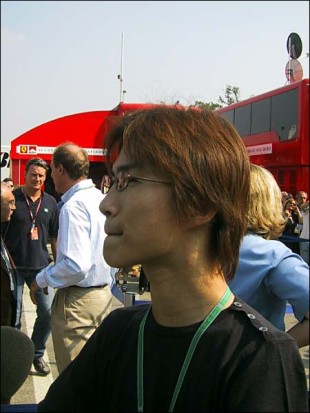

Weekender met with Ototake at his office in Shinjuku last month to talk about the lessons he’s learned in his many careers, provoking controversy on social media to bring attention to ignored minorities, and some of the ways that Japanese politicians could reach out to a younger generation.

Something that impresses you on meeting the Tokyo native is a powerful sense of his poise and self-assurance. Although his first book, “Gotai fumanzoku” (translated in English as “No One’s Perfect”) recounts stories of how Ototake overcame his physical limitations in order to run, jump rope, swim, and play basketball on his junior high club team, it also depicts a young man with a natural talent for leadership. From his elementary student days to his time at Waseda University, he was never interested in just being accepted: he wanted to make a difference in any community that he was a part of.

One of the wellsprings of this strength lay close at home. “When I think about the love and support from my parents, I know that is what made the difference for me,” Ototake, who is a father of three, muses. “If I hadn’t had that, and had been born in this same body, I know that I wouldn’t have the same life that I do now.” It all began, Ototake writes in “No One’s Perfect,” when his mother saw him for the first time. His father knew about his son’s disability but had persuaded his wife that the baby boy had severe jaundice and she couldn’t see him until he recovered. It was only after a few weeks that his mother was able to lay eyes on her son for the first time:

“The words that burst from my mother’s lips were ‘He’s adorable.’ I think the success of this first encounter was especially meaningful. First impressions tend to stick. Sometimes you’re still carrying them as baggage years later. And when it’s a parent and child—that meeting is a profoundly important one. The first emotion my mother felt toward me was not shock or sadness, it was joy.”

(“No One’s Perfect,” Prologue)

“Sumo Is My Soul”

Ototake quickly got involved in the barrier-free movement at Waseda, and following his pivotal role in a student campaign to improve handicapped accessibility on campus, his career as a public speaker began. It wasn’t long before he was giving multiple speeches around the country while still an undergraduate. He also wrote “No One’s Perfect,” which went on to be a smash hit: it has sold nearly 5 million copies to date and is the second best-selling book in Japan since World War II.

Rather than staying on the speaking circuit after university, he followed a lifelong love of athletics and moved into a career in sports journalism. True to form, it wasn’t long before he had established a name for himself as a writer who excelled at getting athletes to open up and reveal themselves. From hundreds of interviewees, though, he recalls one that stands out: the famed yokozuna Takanohana. The wrestler came from a family with deep roots in sumo, and he was legendary for continuing to compete despite a series of painful knee injuries. Interviewing Takanohana shortly before he retired, Ototake asked, “‘Why were you willing to put your heart and soul into sumo the way that you have?’ He responded to me by saying, ’Ototake-san, that’s where you’re wrong. I wasn’t putting my soul into sumo: sumo is my soul.’ For him, it wasn’t a feeling of dedicating his soul to this thing called sumo that was outside of him; rather, it was something he was born to do, and he wanted to put all of himself into it to show that culture to the next generation.”

Battles in the Classroom

After several years as a sports writer, Ototake returned to the classroom, this time as a teacher. Countless examples from his first book demonstrate that his primary school teachers—who refused to coddle him, instead challenging him and coming up with creative solutions that allowed him to take an active role in everything that his classmates did – had as large an influence on him as his own parents.

But as Ototake found when he entered the world of elementary school teaching, his decision to work with his students in an innovative manner was met with resistance from the old guard. Whether it was holding class meetings outside during cherry blossom season or giving his pupils more freedom in their schoolwork, Ototake explains, “I’ve always wanted to do what I thought was best for the kids … My teaching style was definitely a hit with the students, and the parents trusted me, but there were always complaints about me in the staff room.”

It was a resistance to change that prevented other teachers from trying new approaches as well. “I was in my early 30s, and there were teachers who were younger than I was who liked my thinking and the way that I taught. But if those younger teachers were to speak up and say that they agreed with me, that would mean that the powerful veteran teachers would be as hard on them as they were on me.

Ototake with his elementary school students at Tachisuginami Elementary School #4 (photo courtesy of Hirotada Ototake)

“[Japan’s] educational system requires that everyone does things in exactly the same way, in the way that was decided. But that’s a system where innovation can be very difficult, and one in which people who are different – even though they might not have asked to be different – can find it very hard to live in.”

His experience as an elementary school teacher led to his first film role, playing himself in the movie “Daijoubu 3 Kumi” (“Nobody’s Perfect”), but it also gave him a direct experience of the kinds of resistance that reformers can face in any field. The same year he stopped teaching school, he found a new medium for expression that allowed him a freedom he never had before.

Provoking for a Cause

“Being presented as perfect is really something painful for me,” Ototake says about the media’s tendency – until recently – to focus only on his positive message. “It’s not just in print; even when I’ve done interviews on TV, and express how many weak points I may have, those all get cut out when the interview is broadcast.”

Twitter has its strict constraints on the number of characters that can be used in a single Tweet, but Ototake still felt completely free in that social space – his own editor. “Nobody can cut my words and it’s entirely up to me to decide how I want to express my message.” And plenty of people are paying attention: he launched his account in 2010 and now has nearly 810,000 followers. The format has been a remarkably powerful tool for Ototake to achieve one of his main goals: drawing more attention to the situation that minorities of all kinds in Japan face. “Because people in the majority don’t have much interest in the situations that minorities confront, the way I use Twitter is to deliberately use controversial language that draws attention to the issues.” He’s been known to tackle everything from handicapped accessibility to LGBT rights, and his provocative comments often get picked up by the national news. “I think that many people might get tired of hearing what I have to say – many of them are probably saying, ‘Damn, it’s this Ototake guy again!’ But if my online critics take the time to think about what I have to say, it can lead them to look at the issues differently.”

A Legacy of Diversity

The former sports journalist sees the Tokyo Games as a rich opportunity, but argues that the city, and the nation, still need to decide what kind of a message Tokyo 2020 will present to the world. “The first time the Olympics were held in Tokyo, it was extremely meaningful for the country. Nearly 20 years beforehand, the country had lost World War II and was basically a burnt-out field. But from there [along with preparing for the 1964 Games] … you had the development of the Shinkansen, a national highway system, and a general improvement in the development of the nation’s infrastructure.

“But for the coming Olympics in 2020, what do we want to do for the international community, and what do we want to leave behind for the rest of the country after the Games are finished? I don’t think we know yet. I think that one of the greatest legacies to this society we can leave behind with the 2020 Games is a sense of diversity.”

In the long run Ototake hopes to see a joint Olympic and Paralympic games. He recognizes that this is an ambitious goal that isn’t likely to be met within four years. “But maybe decades from now we can look back at Tokyo 2020 as the beginning of that movement. We could have one event that is held for [Olympic and Paralympic] athletes on the same day. Take the Tokyo Marathon: each time it’s held, the runners and the wheelchair marathoners compete on the same day … We could do the same thing for the Olympic Marathon and have the wheelchair athletes competing on the same day as the general marathon runners. If we could do that, I think we can find one kind of meaning in hosting these Olympics in Tokyo.”

Government for All

Through his recent work on the Tokyo Board of Education, his leadership of the anti-littering NPO Greenbird, and his studies at the National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies, one thing has become clear to Ototake: the country’s political climate is in desperate need of change. He takes the World Happiness Report – a study that ranks nations on a variety of factors, including economic stability and trust in government – as a sobering illustration. In the 2016 edition of the report, Japan ranked 53rd. “For a developed nation, that is very low,” he warns. “One of the main reasons is that people don’t clearly see how their tax money is being used, or they don’t feel that their taxes are being used for their good. So they don’t have faith in their political leaders, and they don’t go to the polls. This brings the sense of happiness down further, and it’s a terrible spiral.”

He adds that younger people are even less likely to take an active role in politics, much less go to the polls, which only worsens the situation: “It is mostly older people voting, so politicians are focused mostly on policies that support the elderly. No money goes towards helping the young. How much we can change that dynamic is one of the biggest problems that we have.”

A recently enacted policy that allows 18 year olds to go to the polls for the first time is a step in the right direction; however, Ototake believes that the people on the ballots need to be younger as well: “Now, to run for the Lower House [of the National Diet], a candidate must be at least 25. To run for the Upper House, a candidate must be at least 30. Those Upper House members, even in their 30s, are going to have a hard time reaching younger people. I think that’s a real problem. We should change the system to be more receptive to the opinions of the younger generation.”

A New Choice

Shortly after our interview, news broke that may radically affect the public figure’s career. In a story that ran in the March 24 issue of the Shukan Shincho tabloid, it was revealed that Ototake had love affairs with five different mistresses over the past several years. In a statement made after the story was published, he called his own actions “a betrayal against my devoted wife and my supporters … a sin so serious I can never fully atone for it while alive.” On the evening of March 29, Ototake announced that he was putting an end to any plans for a political campaign this year. The following day, according to the Nikkei Asian Review, an executive from the LDP announced that the party would not be putting forth Ototake as a candidate, despite their interest in the author and educator as a representative of a “society in which all 100 million people in the nation can play active roles,” which Prime Minister Abe has put forth as one of the goals of his administration.

As he explained in his interview with us, he had long wanted the public to understand that he wasn’t perfect, and now the court of public opinion in Japan will weigh the writer and educator’s many positive achievements against this scandal in his personal life. In Europe – less so in America – politics and private affairs are usually kept separate. If a leader is competent, his or her romantic activities may be fair game for the press, but they don’t affect his or her capacity to hold or run for office. In almost all cases, it doesn’t work that way in Japan: being “clean” takes priority over being a strong, capable leader. In fact, this could be one reason that many voters, young or old, have a feeling of apathy when it comes to their politicians, and their political system.

By showing that it was possible to succeed in so many different fields, Ototake has made people reconsider what “possible” means when it comes to people with disabilities – even in the wake of the scandal, he continues to do so. During our interview, perhaps with a sense of the storm that might be coming, he spoke of his dedication to his mission as well as his understanding of the risks and difficulties involved: “For me now, the most important thing is to be able to put my efforts towards a society in which anyone, regardless of what minority they belong to or what circumstances they might have been born into, will have the same chance as anyone else. But in Japan, there are many risks involved in running for office. You have to face a huge amount of criticism, it’s expensive, and it puts a burden on your family. It seems to be a position with absolutely no positives to it at all! If I could achieve my goals without taking the political route, I think I would … But if I do decide to enter as a candidate, I would do it with complete conviction and throw myself into the race with everything that I have.”

Considering what he has already achieved in 40 years, it seems like a great loss for Japan to be prevented from seeing what Ototake could do in politics – were he given the chance.