In his new photo book, “Onago Room,” Shiori Kawamoto opens the door to the mystery of “girls’ rooms.”

For a man who has probably been inside more women’s bedrooms than most people will have a chance to visit in a lifetime, Shiori Kawamoto initially seems surprisingly disinterested in them. The 43-year-old photographer has just released his second photo book, “Onago Room,” and sits at a table in an Oshiage gallery, currently holding a commemorative exhibition for his latest release. “At first I just wasn’t that interested; photographing rooms seemed like it would be a lot of hassle,” he says, laughing.

The project began in 2012 when Kawamoto was asked to take some pictures of idols posing for a photo book, but decided he wanted to pitch something a little bit different to generic portraits and pinups. He had heard about infamous dormitories where female idols were living together, with messy rooms so chaotic they were nicknamed daraku beya, which translates best as “depravity rooms.” Out of mild curiosity, he arranged a shoot at the apartment of a former daraku dormitory inhabitant now living by herself.

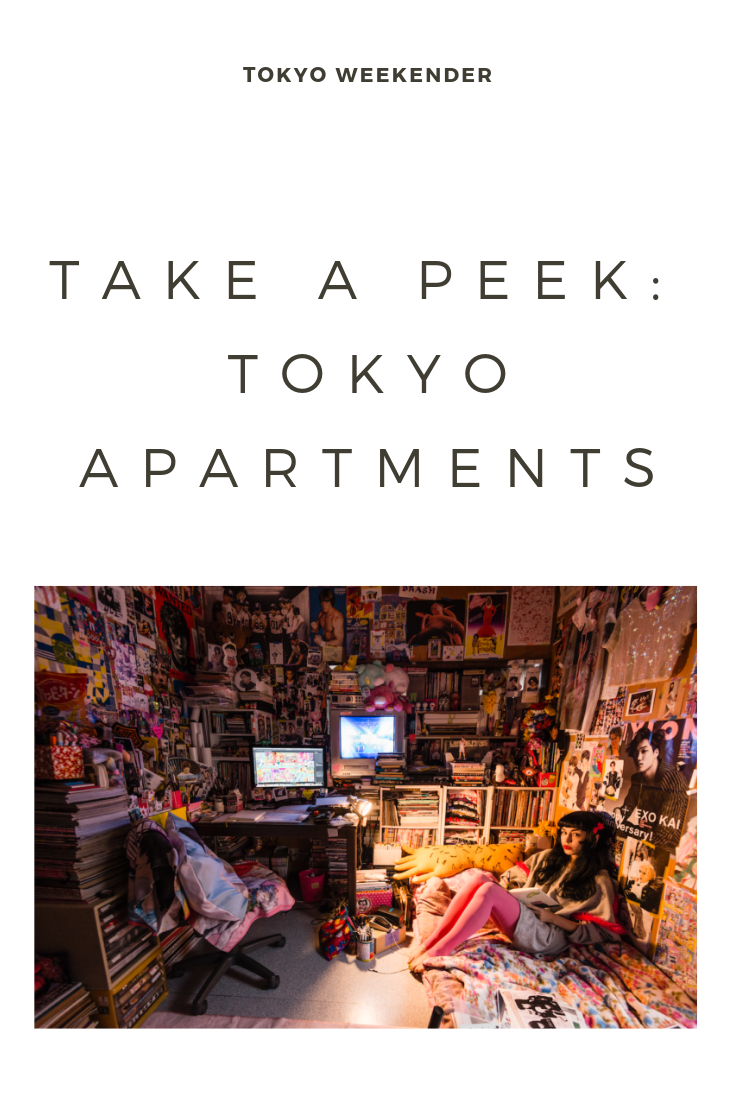

The entire room was plastered with images of smiling anime girls, on posters, wall hangings, and pillows scattered across the barely visible floor; hundreds of faces beamed down from every angle while the owner sat proudly amongst them. The striking impact of the room sparked something in the photographer who was intrigued by this unique form of self expression and felt new motivation to document the incredible scene. After presenting just a small sample of pictures to his publisher, they quickly commissioned him with the challenging task of shooting 50 people within three months to create the content of his first photo book, “Daraku Room.”

After originally seeking out otaku girls (people with an above average interest in a hobby or subject, stereotypically manga, anime, video games, and so on), fanatics, and those with “extreme” rooms, Kawamoto soon discovered that there is something interesting to be found in even the most minimal of rooms. With “Onago Room,” he builds on his previous work, this time with a diverse spectrum of women from a selection of professions including underground idols, artists, musicians, housewives, and company employees. Each is photographed in her home – and these include everything from minimal studios, stylish monochrome pads, and pastel pink hideaways to sprawling nests of eclectic knick knacks. Of course, you’ll also find more of the trademark geeky daraku girls whose rooms are overflowing with characters, creatures and handsome 2D faces.

The photographs document all aspects of the space, with wide-angle shots catching glimpses of ceilings and adjacent rooms, yielding clues about the structure of the buildings surrounding them and life outside. Intriguing as it may be to marvel at the contents and unique decor, it can be just as fascinating to observe the practical usage of space, showing hints of how the girls function within them. The shoots are done organically, with Kawamoto capturing his subjects in their private rooms behaving in their natural way, reading books, playing games consoles, lounging on beds and sofas, yet without the pictures ever feeling contrived or intrusive. Some women choose to maintain a level of privacy and hide their faces behind masks or curtains while others gaze playfully or glance inquisitively, connecting with the visitor in their room.

Whether or not the owner is present in the frame, they are always present during the shoot, a fact Kawamoto actually finds more liberating than being left there alone. These are not really portraits of the figure, nor are they still life images of the rooms; if anything, they could be considered a portrait of the room as a whole, capturing it in its everyday active state without any shame for imperfections and clutter. Empty tissue boxes, discarded clothes, half-eaten snacks, cans of insect repellent – the items pictured might seem unbelievable at first, but assuredly these are real girls’ rooms.

“I try not to be sympathetic to the room when I shoot; I try not to like it too much,” explains Kawamoto. He doesn’t really take notice of the composition or subjects until he reaches the editing process, which is when he considers presentation and selection of the best images. In his mind, he doesn’t separate the person and the background; instead he describes the whole room as “scenery” … “The person, the room, everything is scenery. It all becomes the picture and so becomes the scenery,” he says. Disregarding the distraction of the often overwhelming stimulus, he simply looks for a way to make the pictures his own.

As a man, perhaps especially in Japan, it could be difficult to gain trust to enter such a personal space and shoot so intimately without some misunderstanding of intention, but aside from a few awkward encounters with overbearing family members, Kawamoto has had little difficulty in convincing women to allow him access to their rooms. Initially through work connections at live bars and the underground idol community in Akihabara, he found willing participants almost entirely through word of mouth. These people would then introduce more friends and contacts as well as vouch for his professionalism, which allowed him to build an ongoing stock of rooms. Kawamoto is not sure if photographs of men’s rooms would captivate a similar level of interest. He wonders whether female readers would feel as much fascination for rooms that they might have difficulty relating to, or whether the prevalence of men within many of Japan’s subcultures makes it a less intriguing prospect.

Since a bedroom displaying even a single anime figure or poster can sometimes be enough to warrant the label “otaku” – as well as the stigma that can come with it – it’s not surprising that Kawamoto’s pictures are sometimes met with shock. At worst, the lack of knowledge of Japanese culture (or of subcultures existing within Japanese society) can result in confounded disbelief and loaded gender assumptions about cleanliness, in addition to stern judgment of the women’s habits. But for the most part, reactions to the book have been positive, curious and often verging on awe. There is a warmth to the “Onago Room” pictures that make them inviting to the eye, a welcoming window into a previously inaccessible world.

Discovering his passion for photography whilst at university, Kawamoto describes his early work as “totally not cool.” It was the mid-90s, a pre-internet time when mainstream photography was lacking in style and substance, and a wave of creative photographers – such as Hiromix, Mika Ninagawa, Takashi Homma and Nobuyoshi Araki – opened the door to different approaches to subject matter. Kawamoto was inspired by the resurgence of the medium as an art form in Japan.

Today he is never seen without a camera draped around his neck or resting close beside him, and confesses to a constant need to take photos, “…like eating and sleeping, a part of daily life.” Capturing daily life seems to be the central theme of his 20-year career, whether shooting commercial projects, idol portraits or bedrooms, he finds himself drawn to things a little bit “off the path.” His perspective as someone skirting the line between mainstream outsider and niche insider adds an unexpectedly familiar charm.

“I have a lot of respect for these women and their rooms … I’m not making fun of them,” Kawamoto is careful to point out. He doesn’t want his intentions to be misconstrued, and is aware as a male photographing women’s bedrooms that he could face criticism of exploitation. In fact, the opposite is true. His predominantly undirected shooting methods manifest as a kind of collaboration, and the subject matter makes his photos a celebration of these women and their spaces – places that they have created completely for themselves.

Women like those in Kawamoto’s books may be a minority in Japan, but they do reflect a part of Japanese culture that he is inherently proud of. The greatest compliment to his work is the fact that the daraku girls and owners of these bedrooms are happy with his photographs, and share that sense of pride. Whether it provides viewers with entertainment, inspiration or intrigue, projects like this have a value beyond documents, and hopefully encourage people from all walks of life to take a greater interest in the people, places and communities around them. Few photo books can comfortably deliver such an interesting and unknown slice of everyday life.

“Onago Room” is available on Amazon.jp for ¥2,484. For more info about Shiori Kawamoto, visit shiorikawamoto.com

This article appears in the October 2016 issue of Tokyo Weekender magazine.