“They are piled atop one another high. And the ground will never dry.

It is soaked with the fat of all the people who burned and died.”

– From And the River Flowed as the Raft of Corpses, a book by Chad Diehl featuring Tsutomu Yamaguchi’s poetry

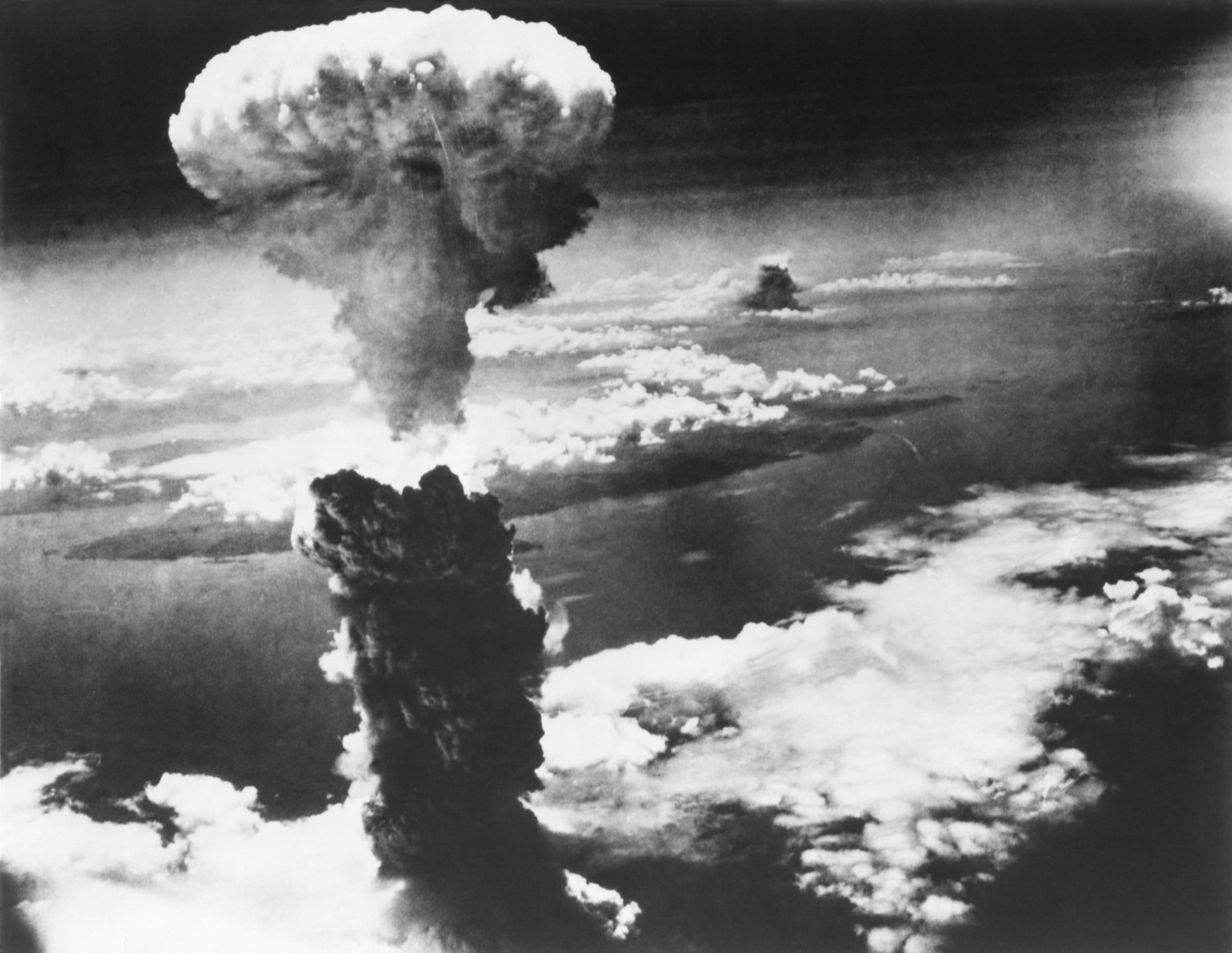

Mushroom cloud over Nagasaki

At around 8:15am on the morning of August 6, 1945, Tsutomu Yamaguchi was heading to his place of work when he looked up and noticed a B-29 bomber soaring over Hiroshima. A small object attached to two parachutes dropped out of the plane and the next thing Yamaguchi remembered was a flash of light like a magnesium flare hurtling towards the city.

The 13-kiloton uranium atomic bomb, known as Little Boy, destroyed much of Hiroshima. Just three kilometers from the epicenter of the blast, Yamaguchi was violently pushed back before instinctively taking cover in an irrigation ditch. A nautical engineer, he’d been sent to Hiroshima three months earlier by his boss at Mitsubishi Heavy Industries to work on an oil tanker. It was supposed to be his penultimate day in the city and he was desperate to get back to his family.

“He had to cross a river that was full of bloated corpses of men, women and children, some of whom were stuck together.”

Suffering from a ruptured eardrum and badly burned on the upper part of his body, the then 29-year-old spent an anxious night at an air raid-shelter with colleagues. Passing through scenes of anguish and torment, he then headed toward to the west of the city the following day to get to the station.

With the bridges down, he had to cross a river that was full of bloated corpses of men, women and children, some of whom were stuck together. These disturbing images would remain with Yamaguchi until his death, yet at the time his main concern was simply reaching the other side. Wading through the dead bodies, he eventually made it across.

Remarkably, the train was still running. Yamaguchi returned to his hometown of Nagasaki on August 8. He went to the hospital to get his burns treated and within 24 hours was back at work. While in the middle of explaining to a disbelieving boss what he’d witnessed in Hiroshima the engineer was thrown back again by yet another explosion.

Two Days of Infamy

Fat Man, the code name for the second of the two atomic bombs used in warfare, was reportedly due to be detonated over Kokura in Fukuoka, but because of cloud cover, the destination was changed to Nagasaki. The number of people killed outright from the blast was somewhere between 35,000 and 40,000 while tens of thousands died later from long-term health effects.

Yamaguchi, who was again around three kilometers from ground zero, survived along with his wife and five-month-old son. In 2009, less than a year before his death, the Nagasaki native became the only person to be officially recognized by the government of Japan as a double hibakusha (survivor of atomic bomb). As filmmaker Hidetaka Inazuka points out, though, there were many others, including Yamaguchi’s colleagues Akira Iwanaga and Kuniyoshi Sato.

“Mitsubishi had factories in Hiroshima and Nagasaki so numerous workers would have boarded the same train as Yamaguchi-san,” says Inazuka, who directed the 2011 documentary Twice Bombed: The Legacy of Tsutomu Yamaguchi (also on Netflix). “The majority of them would have perished in the second attack, however, while it’s difficult to confirm exact figures, we know there were over one hundred survivors.

“Most chose to never speak about their experiences publicly. In his later years, Yamaguchi-san was very open about what happened and became like a spokesperson for hibakusha. What he went through was remarkable and I felt it was very important to make a documentary about it.”

Hiroshima, 1945

Finding His Voice

For decades Yamaguchi’s story was unknown. In 1981 he listened to Pope John Paul II speaking in Hiroshima about war being the work of man and felt he wanted to get his own message across. Protecting his family, though, was more important. Hibakusha and their children faced extreme discrimination particularly when it came to work and marriage as people weren’t given a clear explanation as to the effects of radiation poisoning and many believed it to be contagious.

Another issue was Yamaguchi’s seemingly robust health. He lost hearing in his left ear and had his gallbladder removed, but after a few years his physical injuries weren’t as visible as some of the anti-nuclear peace movement leaders such as Senji Yamaguchi (no relation), so he felt, according to daughter Toshiko Yamasaki, that it would have been “unfair to people who were really sick” if he’d joined the anti-bomb activities.

“His focus was the future; abolishing nuclear weapons and campaigning for world peace.”

In 2005, following the death of his son Katsutoshi from cancer, Yamaguchi changed his stance, deciding to speak openly about what happened to him at the end of WWII. As well as writing memoirs, he appeared in two documentaries, Niju Hibakusha (Twice Bombed, Twice Survived) by Hideo Nakamura as well as Inazuka’s follow-up. At the age of 90, he got his first ever passport and flew to New York to address the United Nations. He also wrote to, and got a response from, former American President Barack Obama about banning nuclear arms.

“Still now, many people don’t know that there were survivors of the two atomic bombs,” Inazuka tells Tokyo Weekender. “The fact that Yamaguchi-san was so close to both blasts and lived was extraordinary. I first met him in 2005 and immediately sensed his warmth and humility. It felt like he had a profound impact on everyone he came across, including James Cameron who took time out from his busy schedule [while promoting Avatar in Tokyo] to visit him in the hospital for our documentary. Two weeks later Yamaguchi-san passed away.”

Nagasaki, 1945

“The Peace Movement Has No Barriers”

Another person the former Mitsubishi employee made a big impression on was Chad Diehl. Author of Resurrecting Nagasaki: Reconstruction and the Formation of Atomic Narratives, Diehl helped out as an interpreter on the Niju Hibakusha documentary, and in the summer of 2009 moved into Yamaguchi’s house while translating his poems for the book And the River Flowed as the Raft of Corpses.

“In spite of everything he went through, Yamaguchi-san always struck me as a man that was at peace with himself,” Diehl tells Tokyo Weekender. “I never saw him express any anger. His focus was the future; abolishing nuclear weapons and campaigning for world peace. I remember one time a reporter asked how he felt about someone from America, the country that bombed him twice, staying in his house. ‘The fact that he’s American has nothing to do with it,’ was his response. ‘The peace movement has no barriers.’

“Coming from a person who’d lived through so much pain, I felt his message carried much more weight,” adds Diehl. “Though it’s a shame he didn’t join the peace movement decades earlier, I’m glad he finally got into it. Peace activism gave him a catharsis and ability to cope with everything. He was on a mission to convey his story and pass on the baton to future generations to ensure something so horrific could never happen again. I think he was an incredible person.”

Tsutomu Yamaguchi

More Than Just a Memory

These are sentiments shared by esteemed journalist and author Richard Lloyd Parry, who interviewed Yamaguchi along with his former co-workers and fellow double atomic bomb survivors, Sato and Iwanaga back in 2005.

“They all told remarkable stories that remained with them throughout their lives, however, when Sato and Iwanaga spoke it felt like I was listening to distant recollections, whereas with Yamaguchi it was more than just a memory,” says Parry. “It was something deeply burned into his core that he’d been living with every moment of his life. He must have spoken about the bombings on countless occasions, yet made it sound as if it was his first time and they’d only happened the other day. Whether you considered him the luckiest or unluckiest man alive, it was truly gripping hearing what he had to say.

Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park

“It has become harder for people to imagine the terrifying realities of nuclear war and that’s a potentially dangerous thing,” continues Parry. “In illustrating the awful physical suffering caused by such destructive weapons, atomic bomb survivors have, in my opinion, played a key role in helping to ensure that a similar catastrophe hasn’t occurred since. To prevent it from happening in the future, it’s important that the testimonies of hibakusha like Yamaguchi are kept alive and shared with younger generations.”

Illustration by Rose Vittayaset