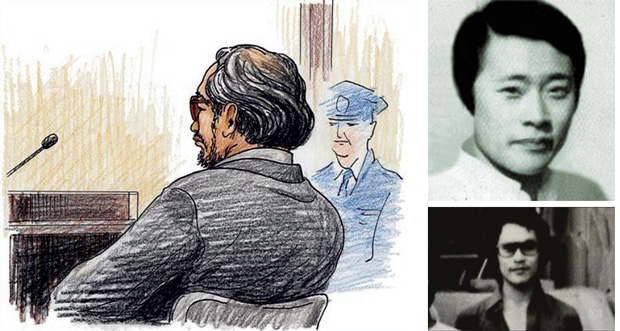

Some of the few existing photographs and court sketches of Lucie Blackman’s accused killer Joji Obara COURTESY OF RANDOM HOUSE

by DONALD EUBANK

February 24, 2011

CONTINUED FROM PAGE 1 | SINGLE PAGE

Obara used multiple names over the years, and the one that he was tried under was only his because he chose it when changing his nationality from South Korean to Japanese in 1971. His parents were Zainichi immigrants — “impermanent” Japanese residents from Korea — who became remarkably wealthy in Osaka after World War II through taxi companies, pachinko parlors and parking garages. He was born Kim Sung Jong, a name that was changed to Seisho Kin as the family rose in prominence in Osaka and then the more Japanized Seisho Hoshiyama before he was sent by his parents to live alone in the upscale neighborhood of Denenchofu at age 15 while attending Keio University’s prestigious high school in Tokyo.

Parry delves as deep as he can into this history, exploring the conditions of the Zainichi ethnic Koreans in Japan, who were no longer citizens of their own country and yet second-class citizens in the country that was the home of their second generation. Despite the Kim family’s wealth, there was always a glass ceiling that no Zainichi could transcend at the time, an invisible racism would keep them out of the mainstream of Japanese society.

But even this background, and whatever strange family dynamics might have existed — Parry reports that Obara’s older brother appears to have been mentally disturbed and his father died under mysterious circumstances during a trip to Hong Kong — can not explain the perverse turn his life took, shut off from other humans outside of his closely controlled interactions with woman whose time he paid for and then abused.

“I was aware that it is very easy to play Doctor Freud. There are suggestive things about his background and past that we know about him: the immigrant parents, the sudden rise from poverty to wealth and the dislocation that brings, the physical dislocation when he left his home as a child in Osaka, living as a rich teen with no adult supervision,” says Parry. “You could look at all of those things and say ‘Ah ha, this is why his personality became distorted.’” But lots of people suffer these dislocations and don’t become serial rapists.”

The most telling thing about his personality was his seeming isolation from the society around him.

“For me, the question that I never answered to my satisfaction was whether Obara had any friends,” says Parry. “I talked to a number of people who knew him from his school in Osaka and Keio School, and from university, but none of them unambiguously described him as a friend. And one of his lawyers said to me that he thought that he lacked friends.”

Though Parry is thorough in tracking down whatever leads he can find, in the end Obara and his wiped-out history are beyond his reach. The killer appears in only a handful of known photos and even when he appeared in court on trial, he made great efforts to sit such that people who attended would never get a full look at his face. There is no one who appears to know him after his time in school, and how he filled his days when he wasn’t assaulting his victims is impossible to determine. The man responsible for so much unhappiness is a void in time.

“When I started out, I was expecting to crack Joji Obara like a nut, and I guess I imagined it like a puzzle, like if I succeeded that I would find a solution for it. There would be a secret,” says Parry. “But I don’t think there is. And perhaps for people like that, the secret is that there is nothing there, that what explains his behavior is not any kind of positive evil, to use that problematic word, but a lack of capacity to make any kind of human relationships.”

In the convenient yet gory tales of Hollywood and pulp serial killers, we are typically given some clue, some way in to understanding the gruesome acts of their central characters. But Parry found with a case like Obara’s — a real world case — that maybe there never is a real world explanation. Given the standard storyline, this could be a source of infinite frustration, but as presented in “People Who Eat Darkness”, it feels like a corrective to all the narratives that have been fed to the public saying that we can find the answer. That Parry refuses to contort himself and the narrative out of shape in the service of finding one — that wouldn’t necessarily be a true one — is the real strength of the book, and suggests a new way forward, perhaps, for nonfiction and fiction alike: That there are some things, despite all our studies of psychology, history, morality, philosophy, that are unknowable and cannot be neatly summed up.

In the end, Parry describes Obara in the book as being all surface, saying that we can only know him by the misery that he has caused. This lack of depth become his definition.

“There is a whole literature about serial killers and psychopaths. I hesitate to use that word, and no psychiatric evaluation has ever been made of him, so I don’t know whether the word psychopath means anything very much or whether it applies to him,” says Parry. “But one of the things that is often said of people who are labeled as a psychopath is that they are very boring. There is very little to say about them except to describe their actions, they lack personality really, because they don’t have empathy and they don’t form relationships.”

“And if you strip relations away from human beings, then what is there left really, except for just biological drives? So in the end, I stopped worrying that he didn’t seem very interesting, and thought that might be the most interesting thing about him.”

An altar in front of the cave near Tokyo on Miura Peninsula where the remains of Lucy Blackman were found on Feb. 8, 2001 JEREMY SUTTON-HIBBERT PHOTO

The depth of Parry’s account of the Blackman case is due to the refusal of Obara to admit any kind of guilt, giving prosecutors years to dredge up information. As well, over the case’s 10-year duration, a host of other people introduced themselves into the narrative, including conman Mike Hills, who could have been sent from Central Casting for a role in a Guy Ritchie movie; the bickering Tokyo sadomasochists; and the racist club owner Kai Miyazaki. Parry himself goes undercover as a barman (“I discovered by that time, 2007, there were fewer of those bars. [Tokyo Governor Shintaro] Ishihara had done his sweep of Roppongi.”), was unsuccessfully sued for libel by Obara (“We have published “People Who Eat Darkness” under the assumption that he would sue us.”) and mistakenly received a package intended for Tokyo’s noisy rightwingers, inciting them to “deal with” him for “insulting the Imperial family”. Whether it was directed by Obara, he never found out.

The Blackman family, who cooperated completely with Parry in his writing of the book, are given a full and fair treatment. Unwilling to play the typical beaten-down victim, Tim, who is divorced from Jane, was lambasted by the British press when he accepted an offer of “consolation money” totaling almost half a million pounds from Obara’s lawyers. Parry tries to cut through all the name calling.

“What I wanted to convey was the extent which they all suffered, and that they are victims of a terrible crime. That seems like stating the obvious, but it really was forgotten in a lot of the vituperation against Tim when he took the money,” Parry says. “It was almost as if he was a criminal in some of the things you read, and he’s not. He is a human being who found himself in a terrible situation and made a judgement.”

After all, the criminal was Obara, the man-shaped hole in a story that blighted everyone left behind, a story that Parry tells with sensitivity and intelligence, giving Lucie Blackman’s life at least some peace and meaning in the end.

PAGE 1 | 2 | PREVIOUS | SINGLE PAGE

External Link:

Richard Lloyd Parry, Wikipedia