Walking down the corridors of Abashiri Prison Museum in Hokkaido, a life-size mannequin suddenly grabs your attention overhead. It’s of a man wearing only white underwear attempting to escape. The figure represents Yoshie Shiratori, a prisoner no jail could hold. Between 1936 and 1947, the man known as the “Harry Houdini of Japan” escaped from four different cells. On the 44th anniversary of his death, we look back at his extraordinary life and daring jailbreaks for our latest Spotlight article. While the fact that Shiratori escaped four times is true, some tales of his escapades may be folklore rather than factual.

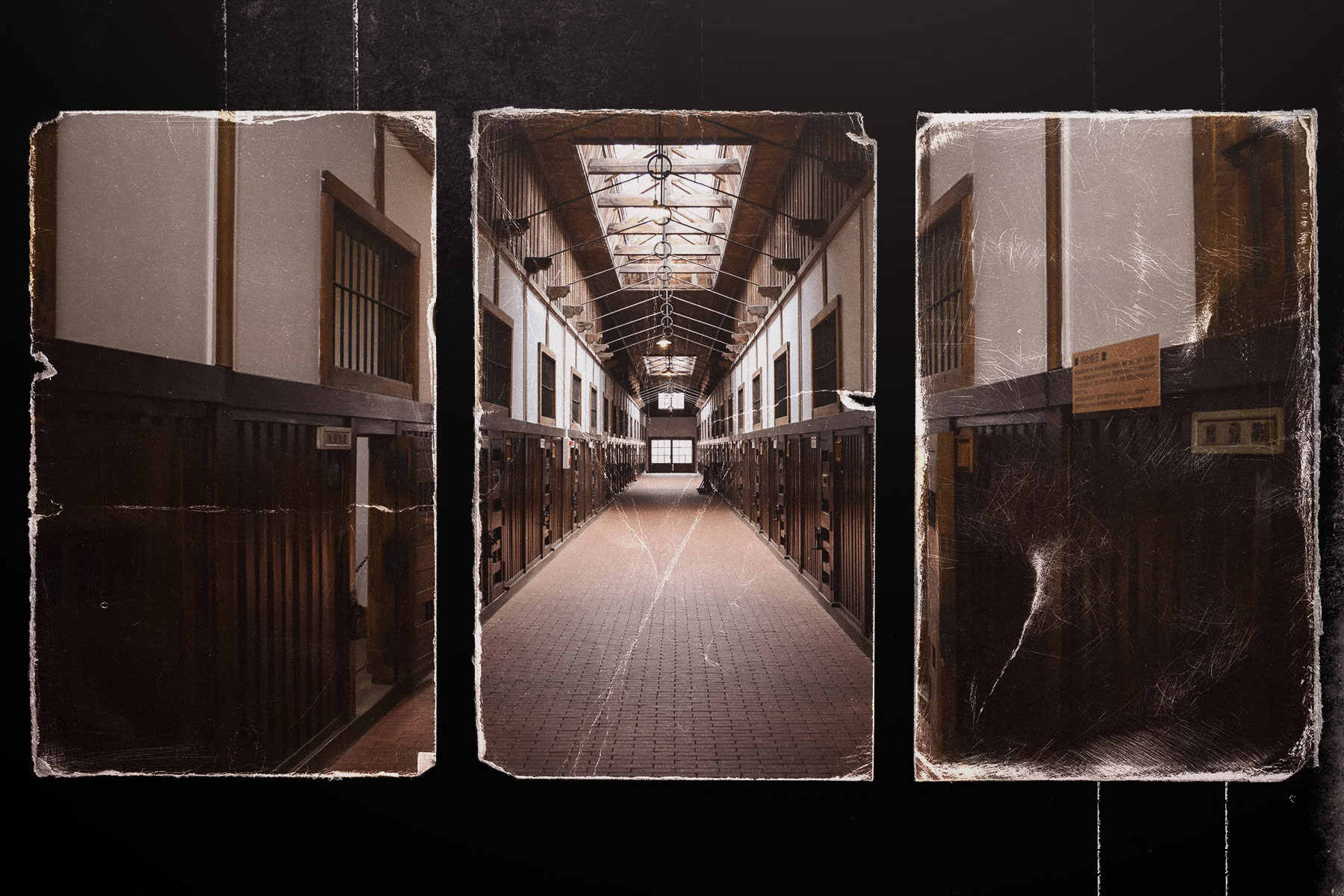

Mannequin of Yoshie Shiratori at Abashiri Prison | Applepy via Shutterstock

Who is Yoshie Shiratori?

Shiratori was born in Aomori Prefecture on July 31, 1907. The middle child of three, his father died when he was very young and his mother then abandoned him and his sister, taking only his older brother to live with a farmer in Akita Prefecture. The two remaining children were subsequently brought up in a tofu store by his aunt. Both helped with shop duties. Determined to pay off his father’s debts, Shiratori got a job on a Russian ship catching crabs when he was 18. A few years later, he tied the knot and had a child, but was soon in financial trouble.

Shiratori turned to gambling and stealing to raise funds and quickly became addicted. On April 3, 1933, he was part of a group of thieves that robbed a merchandise dealer’s storehouse in Higashitsugaru. The adopted son of the owner was then stabbed to death after chasing two of the perpetrators out of the building. Shiratori reportedly handed himself in two years later, when one of his acquaintances was arrested. Though he denied the murder charge, the police allegedly beat and tortured him to get him to confess.

Shiratori spent time in several prisons

Aomori and Akita

Transferred to Aomori Prison, Shiratori often complained about the abhorrent conditions and the inhumane way he was treated by the guards. They responded to his complaints by punishing him even more. As the abuse continued, he studied their movements. In the morning there was always a 15-minute gap in the patrol time. This was his short window of opportunity to get out of there. He decided to make his move in June 1936. Using a metal wire that had been wrapped around a bucket used for bathing, he picked his cell lock and escaped through a cracked skylight. Passing guards assumed he was still sleeping as he’d placed floorboards inside his futon.

While Shiratori was highly skilled at escaping, he wasn’t so proficient at evading capture. Caught stealing supplies from a hospital, he was re-arrested just three days after the jailbreak. Handed a life sentence, he was eventually transferred to Akita Prison. Here he was treated even worse than before and started plotting his second escape. It wouldn’t be easy, though, as he was handcuffed at all times and placed in a cell specially designed to deter escape artists with high ceilings and a small skylight. Taking up the challenge, Shiratori regularly got out of his handcuffs and scaled the smooth copper wall to pry away at the rotting wooden framing of the skylight. He then waited for a stormy night to go out of the window so his footsteps wouldn’t be heard on the roof.

Abashiri Prison | linegold via Shutterstock

Abashiri and Sapporo

This time, it was three months before Shiratori was back inside. He made the mistake of visiting the house of guard Kobayashi, the one officer who’d been nice to him in the slammer, to ask for help in a case against injustice in the Japanese prison system. Kobayashi, though, called the police and Shiratori was sent to Hokkaido’s notorious Abashiri Prison, a place no inmate had ever escaped from. Exposed to the extreme cold while being forced to wear summer garments, he was placed in specially made hand and leg cuffs. Every morning he spat miso soup on the cuffs and the frames of the narrow food slot on his cell door. The salt content oxidized the screws, leading to corrosion. Shiratori saw his chance to escape during the wartime blackout on August 26, 1944. Remarkably, he dislocated his shoulders to squeeze out of the tiny food slot.

Following the most audacious of prison breaks, Shiratori headed to the snowy mountains, staying in an abandoned mine. After two years living off nuts, berries and wildlife, he headed to a nearby village and learned of Japan’s surrender. He then stole some tomatoes, which led to an altercation with a farmer, who he ended up killing. Shiratori claimed it was self-defense, but was this time sentenced to death. At Sapporo Prison, he had six guards surveilling him. With very high walls and windows smaller than his face, they didn’t feel the need for handcuffs. However, as they focused too much on potential ceiling escapes, they forgot about the floor. Shiratori also tricked them by regularly looking up. As they slept, he used miso soup bowls to dig a tunnel, keeping the dirt in a small pocket under the floorboards. Unbelievably, he’d done it again.

Shiratori’s Final Years and Legacy

Shiratori was free for around a year when he was offered a cigarette by a police officer in a park. As this was seen as a luxury item in Japan, he was moved by the gesture. It was at that point that he decided to confess to being an escaped convict and was rearrested. The Sapporo High Court, though, revoked his death sentence, ruling the killing of the farmer as self-defense. Shiratori was sentenced to 20 years and served 14 due to good behavior. Treated fairly, there was no desire to escape. His request to be imprisoned in Tokyo’s Fuchu Prison was also granted. After being paroled in 1961, he did a variety of jobs and was reunited with his daughter. The ex-convict saw out his final days in Aomori before dying of a heart attack on this day in 1979. He was 71.

Shiratori was seen as an antihero in Japan and his exploits naturally fascinated the public. In 1983, esteemed author Akira Yoshimura published Hagoku (meaning prison break), a novel based on his life that won the Yomiuri Prize a year later. It was then more than three decades before the book was adapted into a film made for TV Tokyo. It starred Takayuki Yamada, Takeshi Kitano and Yo Yoshida, while Yoshihiro Fukagawa took on directing duties. Noda Satoru also confirmed that Yoshitake Shiratori, a character in his hugely popular manga series Golden Kamuy, is based on Yoshie Shiratori, the man no Japanese prison could hold.