The award-winning author of Breast and Eggs shares her thoughts on writing about reproductive ethics, the problem with Japan’s patriarchal system and challenging Haruki Murakami on his “persistent tendency for females to be sacrificed for the sake of male leads.”

Who is Mieko Kawakami?

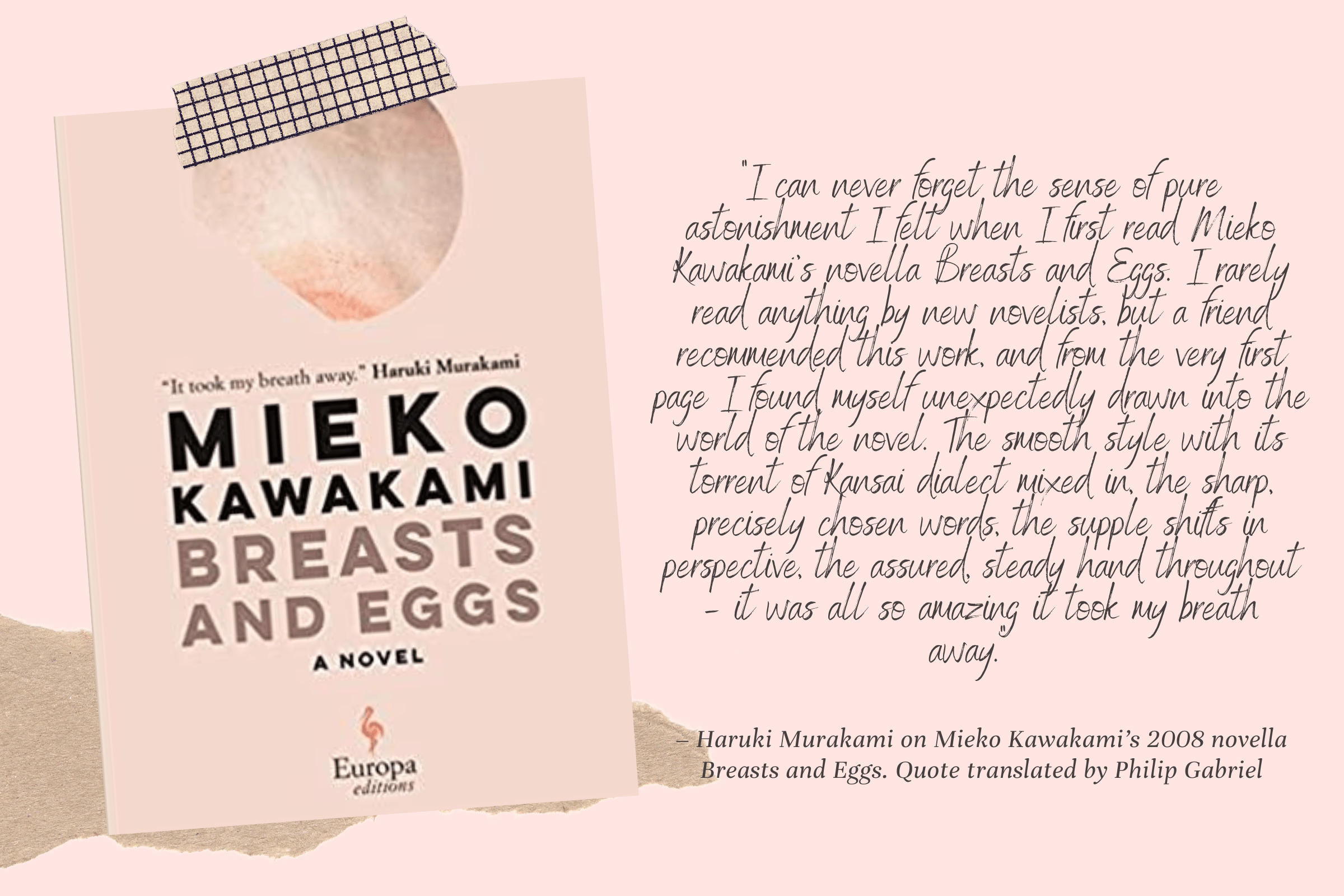

Lauded by literary giants such as Haruki Murakami and Yoko Ogawa, Mieko Kawakami is widely regarded as one of the most exciting and important authors in Japan today. A former singer-songwriter who started blogging in an attempt to boost sales of her music, she attracted a large fanbase with her online musings. The skilled wordsmith then entered the literary world, debuting with the prose poem, “Sentan de Sasuwa Sasareruwa Soraeewa” in 2006. That was followed by two critically acclaimed novellas: My Ego Ratio, My Teeth and the World and Breasts and Eggs, the latter picking up the coveted Akutagawa Prize.

What is Breast and Eggs About?

An intimate depiction of modern-day working-class womanhood in Japan, it asks questions about gender norms. Set across a few days in summer 2008, the story focuses on three characters: narrator Natsu, her older sister Makiko and her niece Midoriko. Makiko, who’s struggling to make ends meet as a hostess in Osaka, arrives in the capital with her daughter for a consultation about breast enhancement surgery. Natsu, a 30-year-old writer trying to come to terms with her own identity, can’t understand why her sister is obsessed with getting implants and neither can Midoriko, who only communicates by writing. Through the teen’s diary entries, we learn of her inner turmoil as she tries to cope with puberty.

View this post on Instagram

Last year, Kawakami brought the characters back in the book Summer Stories, which rewrites the original novella followed by a section that tackles the issues of single motherhood and artificial insemination. An international publication, Breasts and Eggs, was released this spring.

Where Reality and Fiction Overlap

“I knew at some point I would write about reproductive ethics,” Kawakami tells Tokyo Weekender. “I’ve always had an inquisitive mind and as a child often asked existential questions. I remember being shocked when my grandfather died. I must have been around seven and knew his body would be burned into ashes, but I was curious about what happened to his memories and emotions. Adults told me they became stars. [Laughs] It felt like I was being shielded from a big secret. From then on, I would sometimes look at my hands, these things that will eventually become ashes, and vaguely think about the difference between life and death.”

View this post on Instagram

In Breasts and Eggs, Natsu poses several questions about procreation and why people choose to have children. This inquisitive manner is not the only thing she has in common with the author. Both are writers who grew up in relatively poor households in Osaka without any significant male role-models. Like Natsu, Kawakami started working in her early teens after she lied about her age to secure a job at a factory.

“When writing a novel, it’s natural to relate things to your own memories and experiences,” says Kawakami. “In this book there are many points that overlap between myself and the narrator but it isn’t a story based on my life. It’s important to have distance between myself and the people in the novel.”

Who Are Her Critics?

Kawakami pulls no punches in her writing. Male characters are generally given short shrift. She’s critical of the misogynistic attitudes and androcentric views she believes pervade Japanese society. The 43-year-old author is also candid in the way she addresses the scope of the female body, frankly discussing topics such as menstruation, ovulation and nipple sizes. Naturally, this style of writing doesn’t appeal to everyone and Kawakami’s work isn’t without detractors. After Breasts and Eggs won the Akutagawa Prize, Shintaro Ishihara, the Tokyo governor at the time and former winner of the award himself, lambasted the novella. “The egocentric, self-absorbed rambling of the work is unpleasant and intolerable,” he wrote in an article for Bungeishunju magazine.

View this post on Instagram

“I don’t care if people criticize my work, especially if they have no interest in the subject matter,” says Kawakami. “What I do have a problem with is the patriarchal system in this country and the religious-like pressure that people are put under to conform here. Women have long been treated as second-class citizens. This oppressive existence has been internalized by many females.”

“What I have a problem with is the patriarchal system in this country and the religious-like pressure that people are put under to conform here.”

Japan currently ranks number 121 out of 153 countries in regard to gender equality, by far the lowest position of the G7 Nations. Kawakami believes it’ll be difficult to climb to a respectable position while the old guard remains in charge. “If things are going to change, we need that generation of chauvinist politicians, all with vested interests, to retire collectively,” she says. “That and a greater emphasis on sex and gender education.”

On Interviewing Haruki Murakami

Not afraid to ruffle feathers, Kawakami has covered plenty of sensitive topics, ranging from school bullying in the Friedrich Nietzsche-inspired novel, Heaven, to adolescent infatuation in her novella Ms. Ice Sandwich.

She also quizzed Haruki Murakami over the sexualization of female characters in his novels during a series of interviews conducted between 2015 and 2017. A book of those interviews was published three years ago, titled The Owl Spreads its Wings with the Falling of the Dusk. One conversation that stood out was when Kawakami asked Japan’s most well-known living author about his “persistent tendency for females to be sacrificed for the sake of male leads,” to which he replied that he wasn’t interested in “individual characteristics. And that applies to both men and women.”

“The interview was a great experience,” recalls Kawakami. “Of course, Murakami and I have gender and generational differences so it was difficult to question him about feminism, but I think he answered with sincerity. The purpose of these kinds of discussions is not to elicit correct responses but rather to engage in meaningful dialogue. It made me think about how to incorporate the personal and political challenges we face right now into my books.”

For more information about Mieko Kawakami and her works, see her official website at www.mieko.jp or follow her on Instagram. Her book Breast and Eggs was translated into English by

Featured photograph by Wakana Noda (Tron)