When is Japanese milk not milk? What may sound at first like a Zen koan riddle is actually a legitimate question that you may want to know the answer to because a lot of the things in the dairy section of a Japanese supermarket that sure look like milk may not technically be milk. Here’s where things get a little complicated, but also very interesting.

History of Milk in Japan

It’s believed that Japanese people have only been consuming milk for about 150 years. It all began after the country opened its ports to the world and came into contact with Western culture. This is why about 90 percent of Japanese people are lactose intolerant now. They just don’t have a long enough history with the beverage. At least, that’s what people tend to think. The problem is that they’re all wrong.

The history of milk in Japan actually started in the 6th century when Emperor Kinmei welcomed a priest from what is now Korea to his court. The man presented the ruler with volumes on traditional medicine from the mainland, some of which contained recipes for milk-based medication as well as instructions on the raising and milking of dairy cows. A descendant of the priest later presented actual cow’s milk to Emperor Kotoku in the 7th century. The monarch was so impressed, he bestowed the man with a title that essentially amounted to Minister of Milk. He then tasked him with producing the beverage for the imperial court. Soon, royal dairy farms popped up all over Japan, though milk-drinking largely remained an aristocratic pastime.

It’s true that widespread milk-drinking in Japan only developed during the Meiji restoration in the 19th century, but it’s not like they were starting totally from scratch. The country made great strides to make up for lost time, quickly promoting milk as one of Japan’s first superfoods. Soon, the drink became part of everyday life here. So much so, that they now have a lot of different varieties of it, some of which may look like milk but can’t legally be called that.

Japanese Milk Terminology

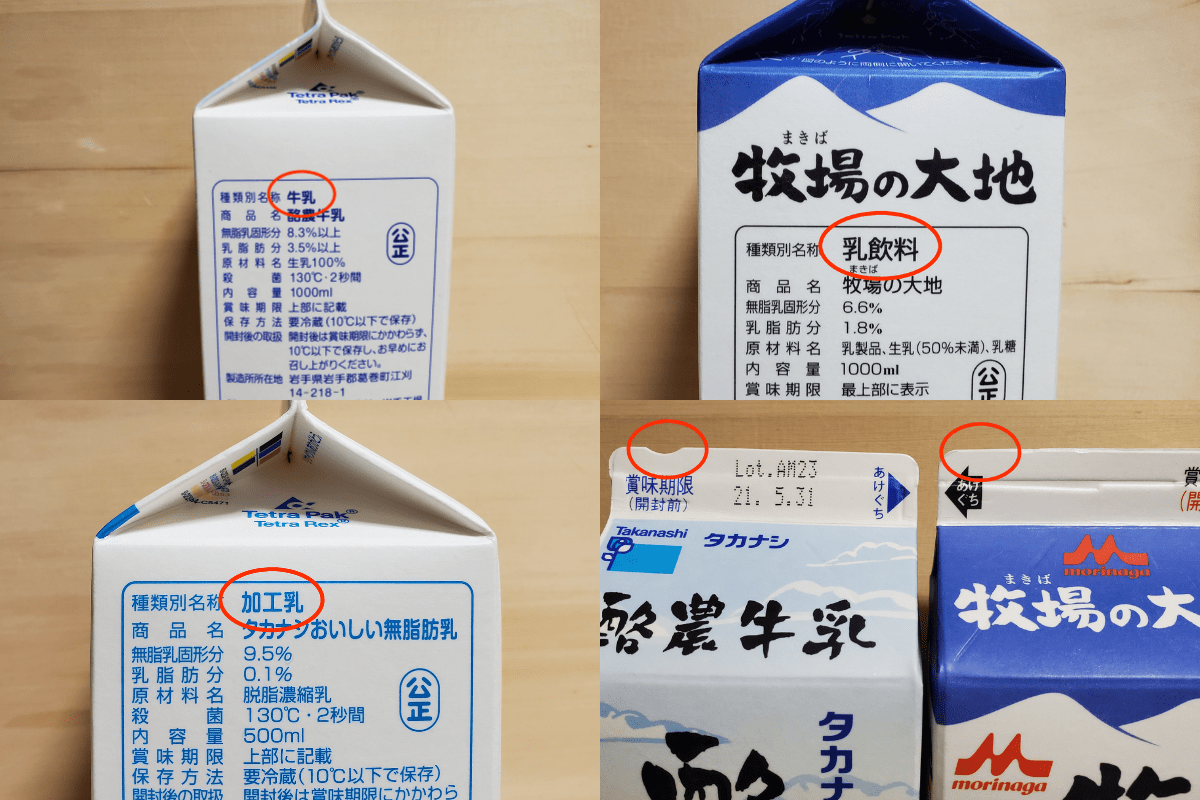

The majority of Japanese milk is of the 3.6 percent fat content, pasteurized variety. In Japan, only that kind of beverage can be called 牛乳 (gyunyu), a term simply meaning “cow’s milk.” You can find it written on the carton, usually not far from the nutrition label. Or, you can use your fingers to feel around for a little indentation at the top of the carton. This has been put there to help blind people identify regular milk at the store (although the practice is not universal). The product may also additionally be described as 成分無調整 (seibun muchosei), meaning “ingredients unadjusted.” This is to help differentiate it from other forms of gyunyu like 低脂肪牛乳 (teishibo gyunyu), meaning low-fat or 無脂肪牛乳 (mushibo gyunyu), meaning non-fat. Another word to look out for is 有機 (yuki), meaning “organic.”

That’s not all that you can find in the dairy section. If you’ve lived in Japan long enough, chances are you might have accidentally bought 乳飲料 (nyuinryo) instead of gyunyu. This label usually appears somewhere on the side of the container so it’s easy to mistake it for regular milk. The same goes for its contents, though some people might notice a slight taste difference. Nyuinryo, which means “milk drink” is essentially gyunyu mixed with non-dairy ingredients like calcium, iron, or even coffee and fruit juice, etc. That said, there’s no chance you’ll get coffee milk when mistakenly buying nyuinryo instead of gyunyu. The outside packaging for flavored milk drinks like strawberry milk is very different to that of nyuinryo. From a legal point of view, however, they’re the same thing.

There’s also 加工乳 (kakonyu), or “processed milk,” which is gyunyu mixed with additional ingredients that are strictly dairy such as cream or butter. To make things even more confusing, there is also the term ミルク (miruku), the Japanized version of the word “milk.” It legally describes all kinds of milk (like goat and sheep’s milk) so it should technically also include gyunyu, but gyunyu can only be called miruku if it has a fat content of at least 4 percent.

Why Do Japanese People Have so Many Milk Varieties When They’re Lactose Intolerant?

To set the record straight, no one actually knows what percentage of the Japanese population is lactose intolerant. Figures range from 40 to 98 percent, so clearly something’s not right. The truth is that a lot of Japanese people have low levels of the lactase enzyme which helps to break down dairy but there is also research that shows that lactase is a very adaptive enzyme and its activity will go up the more milk you drink. That’s possibly why the younger generation handle milk better than their parents. On the whole, though, the country consumes milk on a much smaller scale than the US or Europe. This is a factor in keeping their lactase levels low. In the end, lactose intolerance in Japan might actually be environmental rather than genetic.

Another thing to keep in mind is that “lactose intolerance” is a very broad term. To some, it can mean debilitating stomach cramps while to others it may mean something as insignificant as not being able to absorb all the nutrients from a drink. People are diverse. Just like Japanese milk.