For someone who sings with such bold candor, who garners such critical acclaim, and who answers a journalist’s questions so thoughtfully, Julien Baker can be awfully self-deprecating. In fact the Memphis songstress was downright hard on herself during a recent Q&A with Weekender (ahead of her January 26 performance at Shibuya WWW), offering up intricately compelling, borderline mini novels as replies, and then apologizing for her lack of brevity.

There was of course no need for such humility. Indeed, Baker displayed the same deft way with words during our interview as she does on songs like “Shadowboxing,” and “Hurt Less,” from her latest LP Turn Out the Lights, which made numerous critics’ “best of” lists last year. Aside from the words, the passion and intensity with which Baker sings those songs was also echoed during our Q&A, the pitch of her voice quickly rising and sometimes cracking with excitement as she mulled over hefty topics such as the parallels between the church that rescued her from addiction and the DIY hardcore scene that sparked her passion for music. Below, Baker tells us about all that and more.

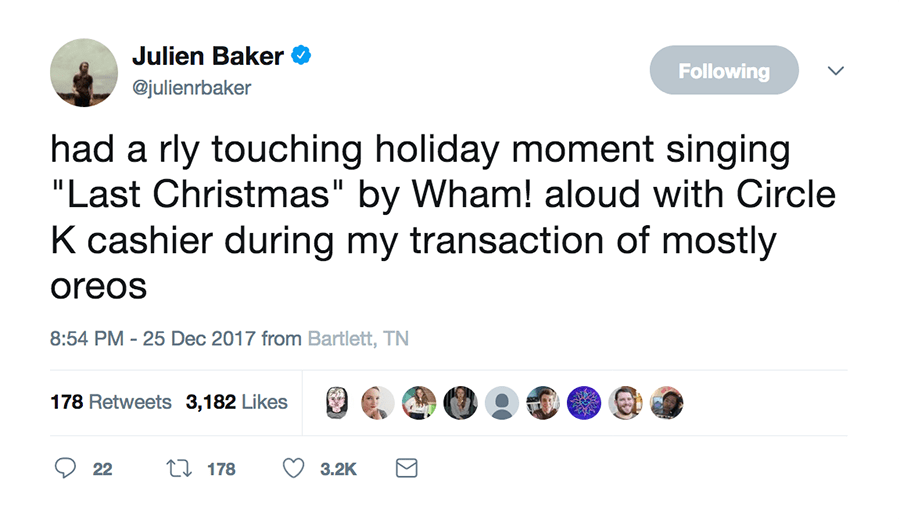

Let me tell you first off: I get a big kick out of your Tweets, especially the one about singing at the checkout with a cashier while buying Oreos during the holidays. Is it fun to show that side of yourself on social media? After all, so many people focus on how melancholy your music can be.

I think you’re absolutely right. People tend to apply the subject matter of the songs to my whole being, you know? And make generalizations about the temperament I have. But I think I’ve found an outlet for those emotions in music, so I tend to channel everything into the art that I create, and I’m able to be a more balanced person because my songs are candid about sadness. I think that equips me with the outlet for those tense emotions, so that I can find humor in things that are even a little bit… well it’s not sad to be buying Oreos on Christmas, but it’s just funny. I think if we don’t seek humor in those situations, and have the levity to laugh at ourselves, they sort of become heavy and sad. It’s a great tool to be able to use, just wholesome silliness in the midst of things that can be very sad.

Is it important to find that kind of levity at your gigs?

Oh yeah. For the most part my banter is joking around, or relating anecdotes. And a lot of times that involves being forthright about my anxiety, or something I’m self conscious about, as a way to defuse the tension I’m feeling. There’s so many times I talk about messing up and then try to make a joke about it. The atmosphere is emotionally charged at my shows, because of the songs, and being able to recognize the comedy in something or defuse it with humor lessens the intensity.

How did you first began to channel your heartache into music? Did it start at church? I’ve read how you had a tough period of wandering the streets in Memphis, then got invited into a church.

My first meaningful connection with music came from alternative bands. Hearing Green Day and Fall Out Boy on the radio, when I was very, very young. Like, fourth grade. And then, I started going to shows at skate parks and hardcore shows. Then I became interested in music that wasn’t played on the radio – screamo, and hardcore and metal core bands. I was really drawn to that energy, of seeing someone have the confidence to just scream into a microphone.

But then, like you mentioned, I got involved in church a little bit later, after I’d been going to house shows. Oddly enough, it was the same concept, in a much different environment. There’s a lot of crowd participation at DIY shows, and similarly in a church setting the songs are a group effort – the congregation is prompted and expected to sing along, and you’re supposed to just be the backing music that carries the worship service along. So there are these through lines, between the two, of people sharing something deeply emotional and sacred.

Those DIY shows are no less sacred than a church service, then?

Yes, that’s at least how I thought of them, as a community. I, uh… [Pauses]. Oh, I was about to take a huge deep dive off of that into, like, what communities should be like, especially the art community. But, go on. What were you about to say?

I’m actually more interested in that. What were you thinking?

I was just about to say that one of my biggest fears is: what music scene am I a part of? And how does that music scene intertwine with other music and art scenes? And how do the people and artists within that community effect change for the benefit of each other? There’s the music and arts sphere. And the activist sphere. And the religious sphere. The purpose of all those things is to give people a common goal, and something to relate to, and alleviate the suffering of your fellow human beings in whatever way and… well, I don’t know. That’s no how I want to word that. Ahh! I’m so sorry… [Pauses]. That’s why I cut myself off earlier. These are thoughts that occur to me regularly, and I haven’t organized them yet.

No, no it sounds great. I prefer this to pulling teeth to get interviewees to answer! [Laughs]. Tell me more about what inspired you to tackle these weighty subjects.

When I was a kid and started going to house shows, I realized quickly that the DIY scene encourages selfless[ness] and sharing. Not just emotions, but also the sharing of burdens. I used to go to this house show collective called Smith Seven. Brian Vernon, the person who ran it, would just loan bands money to print T-shirts, and not charge interest. Sometimes the bands wouldn’t ever make the money back. They’d go on tour, and their van would break down, and they became more in debt to a mechanic than to Brian. And Brian was just like: “I didn’t expect it back. I just saw a need, and I had the means to help.”

I think quite a bit about that now, about the needs people have. And it seems, maybe not quite hypocritical but bizarre, because my music is so idiosyncratic. It’s just stories about my life. But I think that’s the task I’m constantly engaging with: trying to utilize the platform I have that lends itself to the ego, and make it beneficial to others through my lyrics and music.

Did any of that make sense? I feel like it just sounded like a jumble of insanity.

No, no, it made perfect sense. So even though writing about personal experience can be ego driven for other artists I bet – actually I know in your case – that you attract fans because they hear themselves in the lyrics. How does it feel to offer that, and do you have any examples of fans who told you about it?

Well, um… [Pauses]. I think two things about that. First: it’s interesting what you said, about people seeing themselves in the songs. I remember one of the best pieces of advice I ever got was: “Art has to be a bit selfish to be honest.” Which is true. Because if you make art that panders to an imaginative desire of an audience, it will then seem artificial. But making art as self-expression can give people a service for precisely the reason you said, because it is honest.

And, I will say people have come up to me after shows to tell me about these sorts of things. Or I get emails forwarded along to me from Bandcamp or Facebook every once in awhile. But I’m always careful not to retell those stories. I don’t want to be like: “Look at what I have done!” It’s really them doing the thing, they’re just utilizing my art as a tool.

That’s not to say I’m not telling you stories for that reason. I don’t really even catalogue them away in my brain. I just experience the moment of someone telling me: “Thank you, your music did this for me.” And I am very humbled by it. I try not to make a spectacle of it … [Pauses]. It sounds like I’m indicting you asking that question! And that’s not at all what’s happening. I think I just have a bizarre, neurotic self-awareness. So I’m so sorry.

It sounds more humble and unique to me, rather than bizarre or neurotic. It’s a great answer! On the flipside of that, what musicians have offered that solace to you? Who do you listen to, to help you through?

Hmm, let’s see here. Manchester Orchestra, they’re a huge inspiration for me. The first song of theirs I heard was “One Hundred Dollars,” and it was just the lead singer Andy screaming and playing electric guitar. I’d never heard someone be that raw. I thought: “This is a recording of someone freaking out, in a little window in their mind!” And what speaks to me most now is music like that.

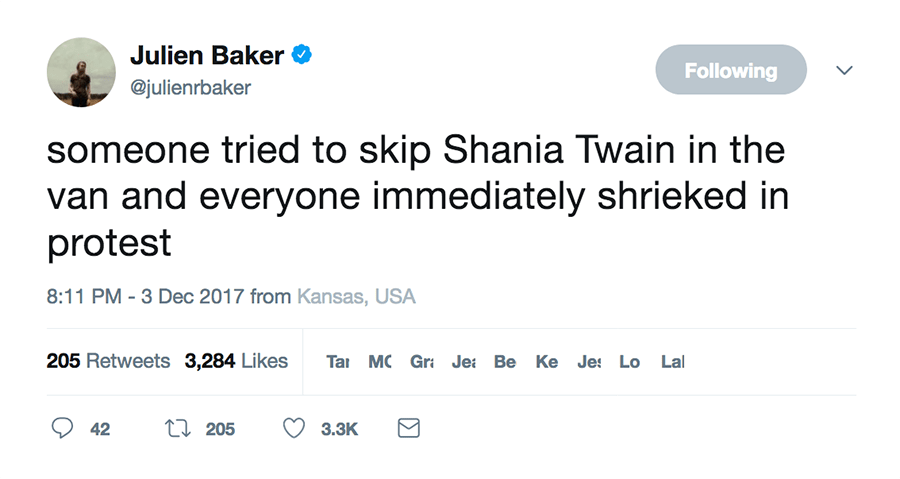

You shouted out a very different musician on Twitter recently: Shania Twain, Tweeting about how you wouldn’t let anyone skip over her songs on the playlist for your tour bus.

Oh my gosh! I have such nostalgia for Shania. When you’re a kid, before I was watching VH1 and hearing Green Day and getting into subgenres, long before that, all I had to listen to was my parents’ music. That’s true for everyone, right? My parents and I went and bought Up when it came out. I know that’s not the super famous album, the one with “That Don’t Impress Me Much,” on it. But I just remember bouncing around on the couch at home, singing Shania Twain songs, because she was one of the first artists I ever heard, and I wanted to listen to it over and over again. I don’t know, it was just catchy music! It’s so funny to me, thinking back on being a kid, running around listening to Shania Twain.

Julien Baker will be playing at Shibuya WWW on Friday, January 26. For more details about the show, visit our event calendar listing.

Main Image: Nolan Knight