Boys for Sale is not a comfortable watch. From the documentary’s very first scene in which a former straight male sex worker reveals how he could bring himself to have sex with men (“Money makes you hard”) to the heartbreaking sentiment of one boy who has not yet turned 20 but states, “I don’t want to live a long life,” the shocking revelations stack themselves high from start to finish. The film, which documents the experiences of a group of young male urisen (rent boys) who live and work together in Shinjuku Ni-chome, not only exposes one of the darker sides of Tokyo’s famed gay district, but also unearths a plethora of related issues in the process.

“We could have made five different films,” says executive producer Ian Thomas Ash. “In the three years it took to produce, we did all kinds of filming, and there were so many things we could’ve focused on, for example gay rights in Japan or the fact that men having sex with men for money is not illegal in Japan, whereas female sex work is. But in the end, our original idea still felt like the strongest.”

Making Boys for Sale

The original idea came about when Ash and the film’s producer and director of photography, Adrian Storey, were looking for a collaborative creative project. Both have spent over a decade living in Japan, and as film makers, say they are drawn to controversial topics and people living on the periphery of society. Storey, who is now based in the UK and works under the professional alias of Uchujin (“alien”), has produced short films for the likes of Vice including one about anti-nuclear sticker artist 281_Anti Nuke, while Ash has won awards for several documentaries, two of which focused on the effects of Fukushima’s nuclear meltdown.

In making Boys for Sale, which enjoyed a sold-out screening for its world premiere in June at the Nippon Connection festival in Frankfurt, the pair spent a full year just visiting different bars in Ni-chome, getting to know the community, and finding out how the male sex industry works. “We had to build up some trust there, and convince them that we would protect their identities if they wanted us to,” explains Storey.

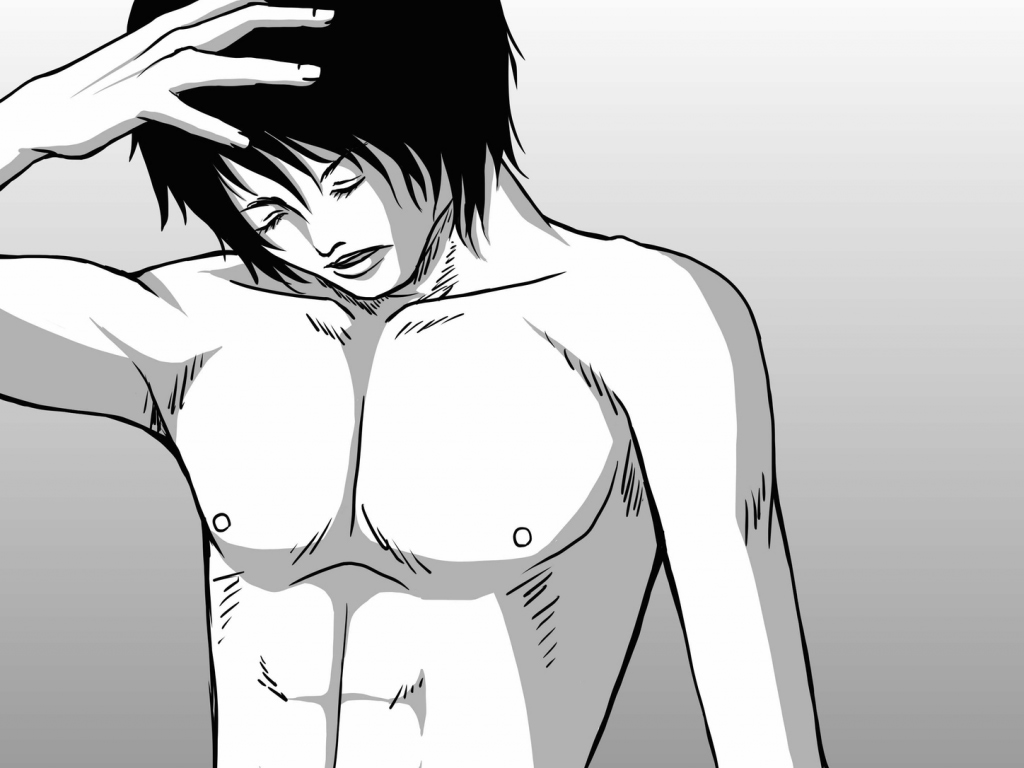

A former “urisen” being interviewed for the documentary

By the time filming began, some of the boys had, surprisingly, agreed to reveal their identity on camera. “I think this was partly because people had come to know us and they understood that this wasn’t just parachute journalism,” says Storey. “But it’s also because they had had time to reflect on what they were doing, and they felt that sharing their story was important perhaps because of what they’d learnt about themselves, and how their work had affected their opinions on things like homosexuality.”

Those who chose not to show their faces donned colorful masquerade masks while being interviewed. While to the viewer the masks might lend an additional layer of pathos to their stories, Ash and Storey initially chose the masks for purely practical reasons. “At first, the masks were a way of just trying to disguise their identities in a visually interesting way,” says Ash. “In the end we realized that giving them the masks to wear possibly helped them to talk more honestly.”

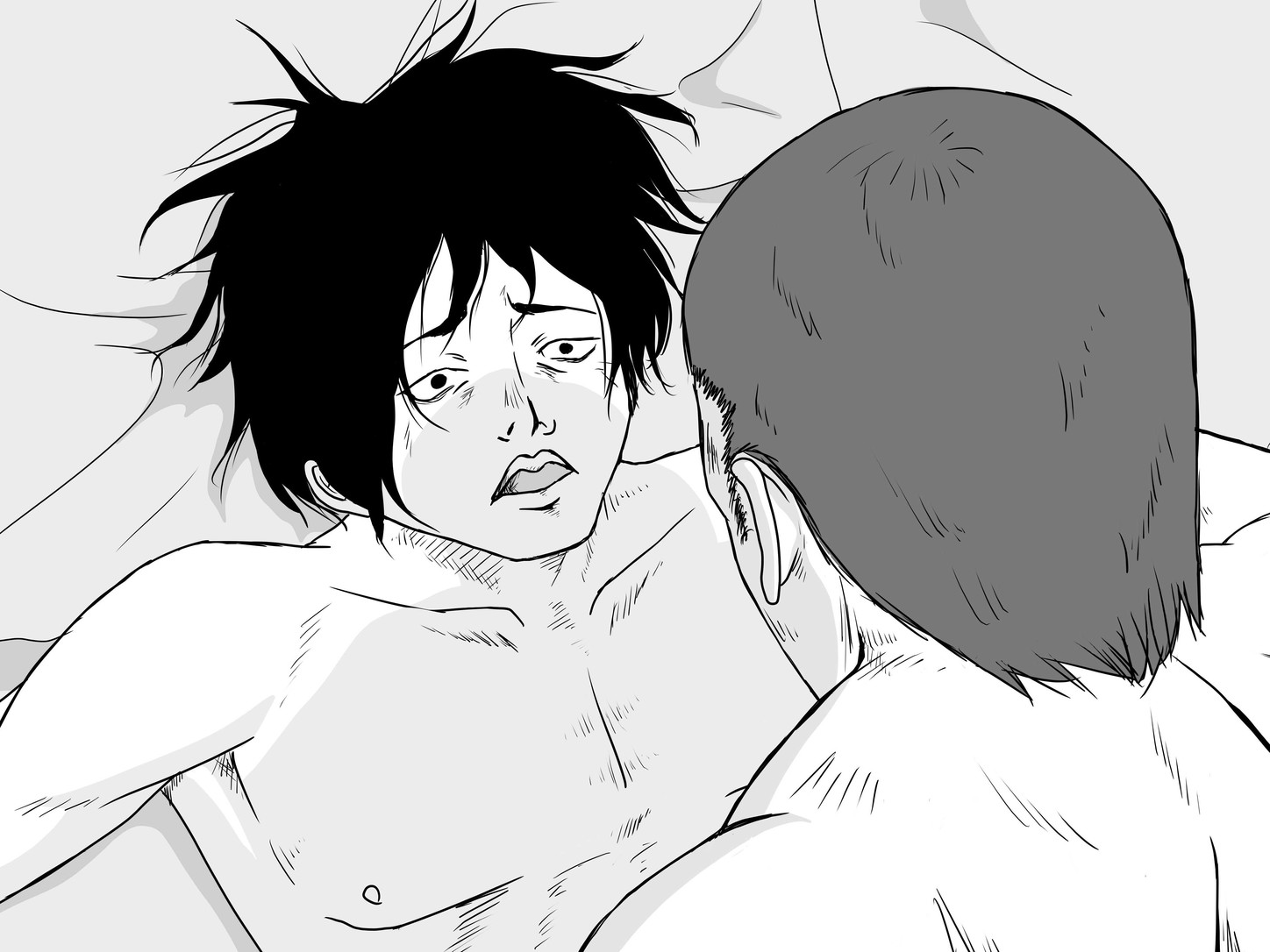

It’s this honesty, in all its brutality, that makes the film such compelling – and at times distressing – viewing. The camera switches between the boys throughout, with each of them answering the same questions. Even though they are filmed individually, the story is carried through their shared experiences, which see-saw between exclamations of how much fun it is living in the dormitory together (eight of them in a seven-mat room) to horrific accounts of being gang-raped.

Although you never see them with customers, they are interviewed inside the sex rooms, giving the viewer a precise picture of the tiny, rudimentary spaces they’re confined to every night. Cleverly, the film uses animated illustrations to cement in the mind what actually goes on in these rooms.

All the boys, save for one, are under 26 (as dictated by the urisen bars’ rules), and many of them service clients up to the age of 80 and even older. They are paid around ¥7,000 per hour, and they work from 4pm to midnight or 2am every day, with just three days’ holiday per month. Depending on how many clients they have, their monthly earnings vary between ¥200,000 and ¥1 million – but 50% of this goes to the bar.

Aside from wondering why they would choose to do this kind of work for such low pay (the reasons they give range from things like family debt to losing everything in the 2011 tsumani), perhaps the most perplexing detail is that the majority of the boys identify as straight; some of them even have girlfriends. Even if they do identify as homosexual, the bar owners instruct them to pretend they are straight. This leads to many a cringeworthy moment as they describe their struggle to reconcile their sexuality with the requirements of their job.

Urisen and the State of Japan’s Sex Education

It also raises questions about societal norms and pressures in Japan. “I think this scenario of straight-identifying men having sex for money with clients who are straight living is a reflection on a society in which it has traditionally not been an option to live openly as a homosexual,” says Ash. “I don’t think that this kind of sex trade is particularly unique to Japan, but the way in which it operates is.”

“Probably the most shocking moment for both of us was when we asked one of the boys if he knew how an STD is contracted and he said, ‘Can men get STDs too?’”

“The things they talk about in the film are quite specific to the way Japanese society works,” adds Storey. “For example, the tendency to be indifferent to issues that don’t directly affect you. And the lack of understanding of sexual health issues. There were interviews where Ian and I were in tears afterwards. But probably the most shocking moment for both of us was when we asked one of the boys if he knew how an STD is contracted and he said, ‘Can men get STDs too?’” Considering the type of work he is doing, where the sex is usually unprotected, his answer is dumbfounding.

Sexual health education, or the lack of it in Japan, is one of the critical issues raised in the documentary. In one scene, the urisens’ manager states that the boys are given training about safe sex, but this is swiftly followed by several of the urisen shaking their heads and saying the opposite. One tends to believe the boys on this point, especially since in a previous scene the same manager insists the nature of the job is explained at interview stage, while more than one urisen claims to have been misled to believe they would simply be dining out with clients or that they would have female customers as well as men.

Reexamining Japanese Society

It’s hard enough as a viewer to walk away from Boys for Sale without feeling desperation for the boys in the film. So how, after spending so much time with them, did Ash and Storey manage to process the experience? And how has it shaped their views on Japan?

“Everyone talks about how homogenous Japan is,” says Storey. “But as soon as you scratch a tiny bit below the surface, you start to realize that’s not true. Japanese people are as diverse as everybody else; there is a dark side, there is all this undercurrent going on – the same as everywhere else. By making a documentary about the fringe of society, you just have it reinforced to you that all these things are going on here. Japan is not unique; it’s not a homogenous, Hello Kitty wonderland … You have to find a way of doing what you can and then letting go. And in some way, making the film and getting it out there is part of processing the emotions.”

Ash adds: “It would be a shame if we walked away and thought ‘I feel sorry for them, and something like that would never happen to me.’ I think we have more in common with people in these situations than we don’t. We have a lot to learn about what it means to be human, and to have empathy. And to not judge people for whatever choices they’ve had to make.”

Boys for Sale was directed by Itako, and all illustrations are by N Tani Studio. The film is being screened in July at LGBT film festival Outfest in Los Angeles. Watch the trailer below, and find out about upcoming screenings at boysforsale.com