Ai Weiwei cuts a curious figure in photographs. The heavyset and bearded Chinese artist carries himself with a larger-than-life air and the look of a Tang dynasty poet. And his reputation is very nearly equal to the task—he is both a looming figure in contemporary Chinese art, and its enfant terrible.

Ai, who lived and studied in the U.S. for more than a decade, is no stranger to thumbing his nose at Beijing. He once did his best to disrupt the Shanghai Biennale by co-organizing a concurrent art festival with an explicative English title that told the larger, corporate festival exactly what it could do. He also created a series of photos of himself giving the finger to Tiananmen Square, the German Reichstag building, The Eiffel Tower, and the White House, equally. The exhibition was closed down by Chinese police. But it made waves.

However, the Mori Art Museum’s exhibition Ai Weiwei: According to What? seems more keen to smooth those waves and draw attention to his most famous (yet arguably least impressive) credential: working as a design collaborator with Herzog & de Meuron, the firm that built Beijing’s National Stadium—the project which caused Ai to refer to the government’s approach to the 2008 Olympic Games as a ‘pretend smile.’

Most of Ai’s work is conceptual sculpture and installation, though he ranges widely into film, photography, performance, and even architecture. His sculptural works often circle around measurements and simple forms. Ton of Tea, for example, is a single ton of tea leaves compressed into a perfect cube, one meter on each side. As a form, it is a literal unit of measurement in both weight and shape—and even in material when one considers the historical importance of Chinese tea exports.

A new installation specifically for the Mori echoes this work. Cheekily entitled Tea House, the piece features a small house built of solid blocks of tea; there is no space inside to enjoy a cup, so the viewer is left to ponder this odd reversal of structure and inhabitant, nourishment and body.

A new installation specifically for the Mori echoes this work. Cheekily entitled Tea House, the piece features a small house built of solid blocks of tea; there is no space inside to enjoy a cup, so the viewer is left to ponder this odd reversal of structure and inhabitant, nourishment and body.

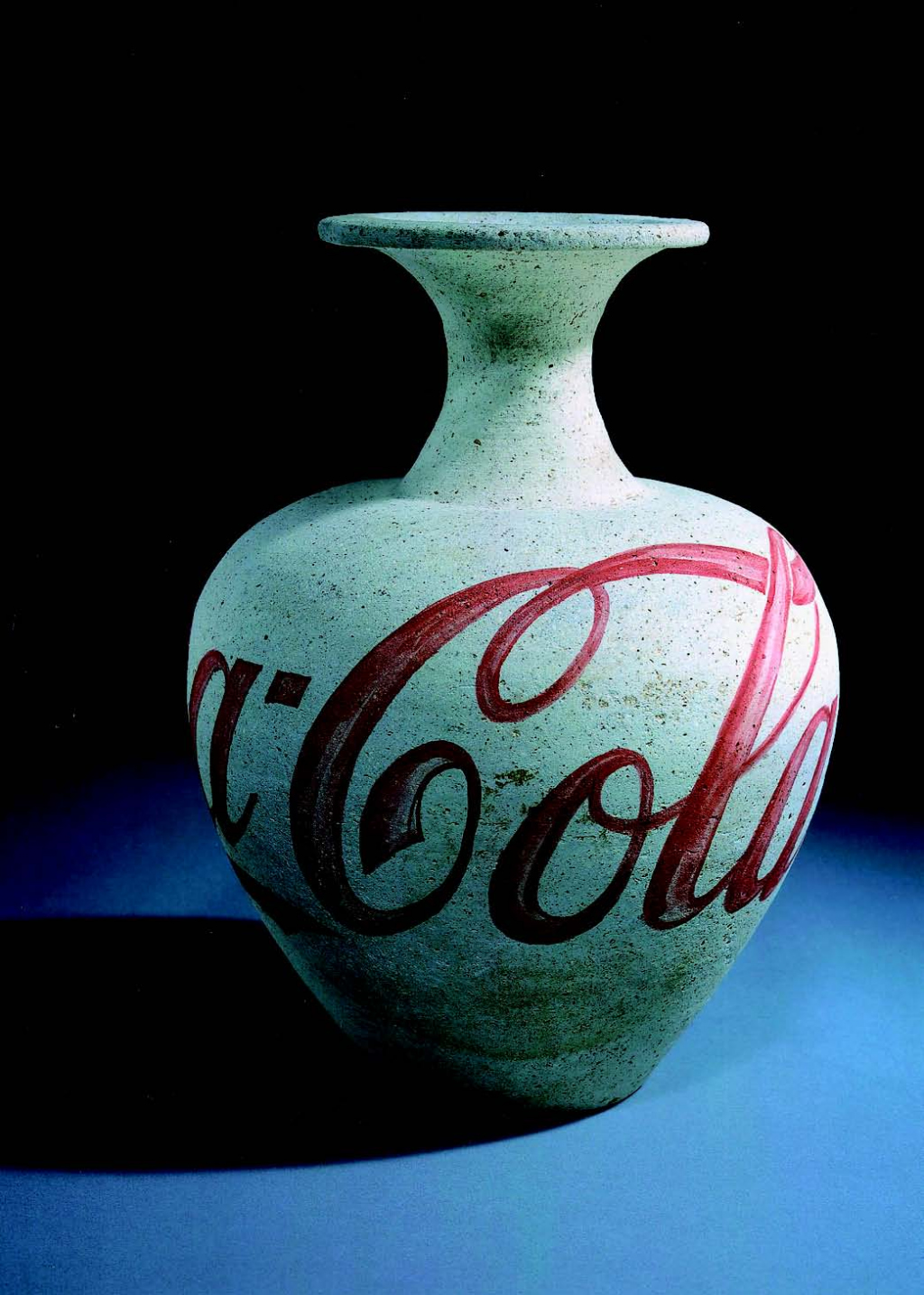

Other works focus on the destruction and re-construction of the past. Frequently collaborating with traditional craftsmen, Ai takes apart antique furniture and reassembles it in useless configurations, or uses the pillars from demolished temples to construct seamless sculptures that hint at China being built on the remains of its own torn-down history. He also comments on the seeming disdain for history and the push to modernize, by re-painting valuable antique vases and urns with Coca-Cola logos or glazing them with household paint, rendering them valueless. In Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn, Ai does just that—and in three successive photos we watch an irreplaceable piece of history shatter at his feet, as he looks on, impassive.

If there is a drawback to this show, it lies in the vanilla presentation of an otherwise critical and broad-reaching artist. Ai is an outspoken proponent of democracy and individual freedom, and while many of his works look pretty in a gallery, they have simmering political arguments beneath the surface. According to What? wants to present a kinder, gentler Ai Weiwei, but risks cooling his criticism with safe and conservative packaging. So if you come away with any creeping impressions of the artist as a raving nationalist…take those with a ton of salt.