by Owen Schaefer

In many ways, the history of art is a history of visual trickery. The phenomenon of seeing faces in knotholes and shapes in the clouds is an intrinsic part of the way the brain works, but the act of recreating three dimensions on a two dimensional surface is, at its very root, an illusion. And when Western art began to pursue realism, some even felt painting had become downright heretical.

For the sake of simplicity, Bunkamura’s Visual Deception exhibition does not wander back to the cave-painting days when we first learned to outline bison in red ochre. It begins, instead, where the real trickery began: with trompe l’oeil―literally ‘to trick the eye’―paintings that are rendered to appear as carved frescoes, cupboards that appear to open into the wall, torn documents lying neglected behind shattered picture frames, or curio shelves revealing odd contents.

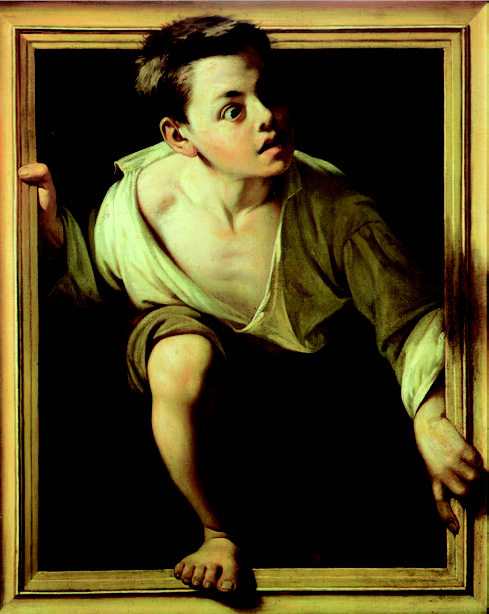

Roughly chronological, the first half of the exhibition is a weighty helping of 16th–18th century paintings, which aims for instructive over inventive, hitting visitors early with the heavily advertised Giuseppe Arcimboldo’s portrait of a man assembled in vegetables, and Pere Borrell del Caso’s Escaping Criticism, in which a figure seems keen to escape his picture frame.

Most of these works are essentially curiosities, and while many are beautifully rendered, this lesson in the basics begins to suffer slightly from an overabundance of dead hunting fowl and yellowing envelopes. But there are several highlights to the show that are well worth seeing.

A section of Japanese works from Kuniyoshi Utagawa and others make some clear contrasts when compared against the Western examples, and Kyosai Kawanabe’s image of a ghost leaving the frame of a painted scroll is a nicely macabre reminder of the late Edo obsession with things that go bump. And a particularly focused section has been devoted to works by Magritte, Dali and Escher.

While only a few of the chosen Magritte and Dali works are well-known, it’s a great opportunity to see so many in one place. And while it may seem obvious to include these illusion-loving artists, seeing their work juxtaposed under the theme of deception is an interesting way to reexamine the different motives that drove their creators.

The final part of the show heads into the territory of contemporary art, and while painting a false cabinet on the wall would draw yawns from the current art scene, exploration of the senses and assumptions about the visual field may well be more active than ever.

I was especially pleased to find Anish Kapoor’s Void No.3 on display―a Turner-prize favorite. Kapoor’s squint-inducing sculpture makes use of a black so utterly light-absorbing that even up close it is almost impossible to tell whether the object is a spherical or hollow―oddly disturbing and soothing at once. Lisa Milroy and Chuck Close offer examples of photo-realistic painting, Naoki Honjo’s tilt-shift photos reveal the flaw in photographic visual assumptions, and Patrick Hughs’ Sea City will blow your mind―or at least make your eyes ache, just a little.

Visual Deception is a light and appealing show, but be warned: it’s also a popular one. You may end up waiting just to see some of the works, as the slow conveyer of viewers moves past. Go on a weekday, and go early. And since there are only a few days left…go soon.