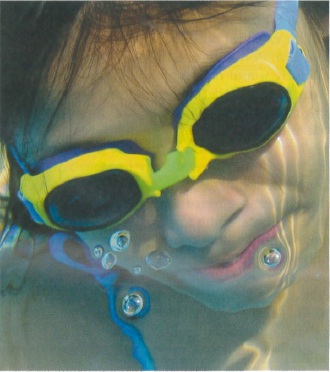

Remember those days of summer, when you slapped on a swimsuit (or not) and leapt into any body of water available, carefree and grateful for the cooling bliss of that pool, lake, river, or splash park? Well, in this spirit, I approached a Tokyo pool with my infant son years ago. And there, wringing dry the spontaneity of the moment, was a huge list of rules for swimmers. Were there so many rules back when I was a kid, or am I just now noticing because I have to be The Responsible Adult? Regardless, in Tokyo today, there are lots and lots of people sharing the water, and many of the guidelines are designed to keep bacteria to a minimum (see below for Tokyo Metropolitan pool rules.)

But, even with the best sanitation efforts, sometimes things happen. If your child gets a rash of tiny, sand-like pimples which, in a day or so, begin to look like blisters filled with clear liquid, you might think: chicken pox. Unless your child has already had chicken pox. In which case, you would have to wonder, as I did, what the heck? I went to the doctor (you should, too, for a professional diagnosis). “Chicken pox, redux?” I asked. This can’t be happening. In fact, the doctor informed me, it wasn’t. My child had something that sounded monstrously worse: “molloscum contagiosum.” “Could I trade that for Chicken Pox?” I asked.

Molloscum Contagiosum sounds contagious (it is) and like a deadly Hogwartsian curse, or at the very least a skin condition related to mollusks, which can’t be good unless you’re a short-necked clam. “You’ve discovered this rather late,” the doctor scolded me, “and it will get worse before it gets better.” I flashed on an image of my child covered with bumps like an Okinawan bitter cucumber. And then I remembered drying my hair with his towel. “Could I get it too?” The doctor nodded. “What’s the cure?” I asked, now on the edge of my plastic consultation stool. “None,” the doctor said, and I swear he was enjoying himself just a bit. “But it’s not fatal.”

Well, don’t ask the child about THAT. The Japanese name for this fairly common viral infection is “mizuibo,” or literally, “water warts.” You can get molluscum fairly easily from pools or splash parks because most sanitation systems are ineffective against viruses. The “cure” offered to me by the first doctor was to “pinch off the lesions with your fingernails, and try to prevent the liquid from spreading.” Apparently, the fluid inside each little vesicle helps the warts to colonize. On careful inspection, you can see a whitish “seed” inside, which causes a slight umbilication on the peak of the blister (one detail doctors use to differentiate the molluscum pox from the chicken type). Pinching out that seed is key to eradicating the blister, which bleeds after removal, and then ideally should be swabbed with an antiseptic.

Do kids enjoy this process? Don’t count on it. At the first pinch-athon, mine had a reaction that brought the neighbors running. I made appointments with three separate doctors before one, a dermatologist, whipped out her curette, a little tool with rounded pinching loops that makes the removal process faster, less painful, and more sterile. She swabbed with antiseptic and then bandaged the popped blisters to prevent the liquid from spreading and to inhibit scratching. We were free of them within two weeks.

All is all, molluscom contagiousum is a pretty benign virus, but in rare instances, the blisters can spread to the eyes or genital regions and cause serious complications. Left untreated, some cases resolve spontaneously within several months, but others drag on for years. The whole event can be embarrassing for kids. It’s important to keep the infection covered while playing, and out of courtesy to others, the child should not go into any public pool, bath, splash park, etc. until the blisters have vanished entirely.

Most parents decide to do battle immediately. Alternatives range from cryotherapy (freezing, also painful), application of comfrey ointment (mostly for anti-itching and soothing purposes), vitamin B supplements to boost skin health, vitamin E applied topically, and a wide variety of new prescription creams (which, if effective, generally show results within 3-4 weeks). The pinching method — medieval as it sounds — gets the widest approval among mothers I spoke to. It seems the fastest and cheapest method, and leaves no scars if properly sanitized. Most go get the diagnosis, pinch like mad, get well, and dive back into the pool-cool splashing summer scene we started with!

Tokyo Metropolitan Pool Rules

- No beverages, body oils, masks (goggles okay!), or toys allowed. Some pools forbid floaties, too.

- Bring a swimming cap to indoor pools.

- No swimming if you have a fever, diarrhea, lack of sleep, or have been drinking alcohol.

- Before swimming, use the toilet, then shower off thoroughly afterwards. Remove cosmetics, hail treatments, and jewelry. Most city pools do not allow soap or shampoo in the showers.

- Do not share towels with family or friends.

- Do not blow your nose or spit into the pool. Or do other, um, things.

- After you swim, rinse your eyes, gargle, then wash your entire body thoroughly in the shower.

- Do not run in the pool vicinity.

- Follow the lifeguard’s instructions. Get out of the pool promptly for the hourly water checks.

- Call ahead to determine age limitations; some do not allow toddlers or infants, while others have wading pools available.