by Kirk R. Patterson

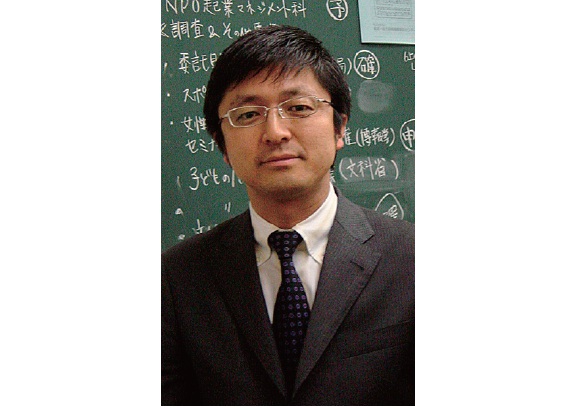

NOBUHIKO TAKEUCHI (38), a native of Nagano Prefecture, received his B.A. and M.A. in Psychology from Tsukuba University. He is the Executive Director of Education Reform Networks, a non-profit organization (NPO) that is dedicated to bringing the private and public sectors together to foster reform of the Japanese educational system.

Q: How did you get involved in efforts to reform the Japanese educational system?

A: As a graduate student, I did my thesis on free schools, which are alternative schools established for those students who drop out of the conventional educational system. Prior to getting involved in these schools, I shared the prevailing view that somehow the students themselves were to blame for not being able to study in regular schools. But then I realized that the educational system itself was at fault for failing to motivate students and to help each student realize his or her potential.

My first job in the field was with Tokyo Shure, an alternative school. That was a turning point in my life, leading me to commit myself to helping provide a wider array of educational options that could satisfy the needs of all students. I then worked at Yoyogi Gakuen, a leading juku (cram school) that established an NPO to provide information about free schools nationwide to the 100,000 students who have dropped out of conventional schools. I worked there for over six years, before leaving in 2003 to establish Education Reform Networks (ERN).

Q: What is Education Reform Networks?

A: ERN is an NPO that strives to involve a wide range of people from both the private and public sectors in educational reform. In the past, education-related matters had been left largely to those in the Ministry of Education, local education committees, and others directly related to education. Education, however, is too important to be left just to those with a vested interest in maintaining the status quo.

Q: How does ERN attempt to realize its mission?

A: We have two basic areas of activities. First, we disseminate information on educational reforms and alternative educational approaches. For example, we hold symposia and other events on education “tokku” (special economic zones), free schools, and other topics; provide information to the mass media; arrange study tours to the United States; and take members of industry and the media to free schools.

In April of this year we started a new initiative, which is to promote project-based learning, a teaching concept developed in the United States. In this approach, instead of students studying individual subjects, they gather information from various fields and apply the information to a specific project over a five-week period, culminating in a final report and presentation. This integrated approach helps students to identify issues, to develop their ability to address issues, and to cultivate their presentation skills.

Q: What are the major issues facing the Japanese educational system?

A: Japan needs to be more open to alternative educational models. For example, it needs to find ways to make it easier to establish and operate charter schools, which are community-based schools that operate outside of the regulations governing traditional schools. It is now technically possible to operate charter schools within education “tokku,” but we need to find ways to get the financial support necessary to make them accessible to all families while maintaining their curricular and administrative freedom.

In the past, the Ministry of Education was not open to the idea of charter schools and other alternative approaches, nor was it willing to accept that NGOs could play a positive role in educational reform. Recently, however, the Ministry seems to be more flexible, more willing to work with NPOs, and more open to considering public/private cooperation in the operation of charter schools.

Ultimately, the real issue is what happens in the classroom. What does the student learn? How is the student’s potential developed? And, therefore, we need a means of evaluating what happens in the classrooms of free schools and other alternative institutions. Such an evaluation system is necessary for parents to be able to confidently select schools for their children and for society to know that the schools are preparing their students for adulthood.