Beautiful, practical and affordable, you can’t go far wrong with a Zuan, says Meg Nakano

JAPAN CAN be so complex, and display such visually appealing works of art, in such variety. You, on the other hand, simply have good taste and good sense, and a budget that runs generously into “one-comma digits.” Wouldn’t it be nice to get something original and extremely well-executed by a master artist? Something that would fit in well with your decor back home, and provide conversation topics wherever you live? Something that you could afford?

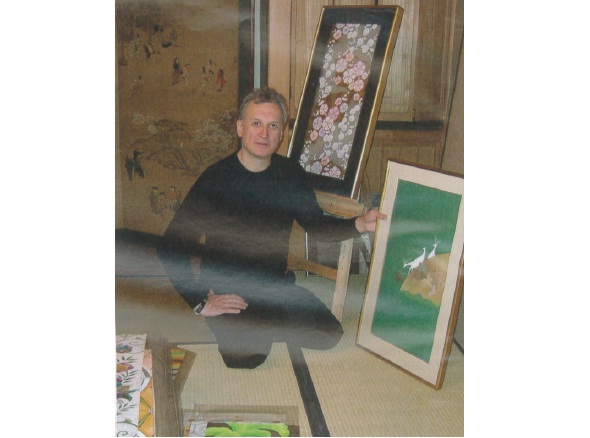

Consider, then, the latest discovery of George Godoy of George & Sandra Godoy Antique Japanese Screens & Fine Art. A new source of art that is traditional, astoundingly fine, and affordable as well: works by obi zuan masters.

How can it be both traditional and new? Well, “zuan” means “design plan” and none of the Japanese firms in Nishijin, where the best obi have been woven for centuries, considered the design plans they used for weaving obi as independent artworks. The zuan have been considered trade secrets, registered and guarded as jealously as the Silicon Valley IC developers guard their circuit designs. Yet the techniques, inspiration, and visual idiom have all been identical to the more formal art media. Their artists’ guild has demanded the highest standards of technique and precision, and has been both highly conservative and highly competitive. Fashion communities after all, whether here or in Paris, demand innovation and style.

But times are not what they once were for kimono and obi weavers, and George Godoy was able to obtain approximately 3,000 of these obi zuan (for a price) on two conditions: “One, that I not reveal my sources, and two, that I not make obi from them.” He easily agreed.

So exactly what kind of designs do obi, the broad belt or sash worn with kimono, display? When you begin to examine the zuan, you realize exactly how much variety there is — only the general dimensions and the fact that the zuan are hand-painted originals remains the same. Pigments may be flat or raised, matte or iridescent metallic, muted or vibrant. Themes may be natural or geometric, modern or from an identifiable historical tradition, simple or intricate. Obi are meant to coordinate with kimono and make a statement about the person wearing them. The zuan now do the same thing in a frame on a wall. Some designs say “authority,” others “old money,” “trendy,” “organic,” “bold,” “gentle,” “religious,” “rich,” or “sexy”, all in good taste.

How old are the Nishijin traditions? Weaving started in this northern area of Kyoto during the Heian period (794-1185), with intricate designs in silks. In the civil war between 1467-1477 the weavers evacuated south, to the trading port of Sakai, where they learned the art of weaving gold brocade and silk satin damask from visiting Chinese weavers. They took the new techniques back to the Nishijin area when the war was over. The Chinese phoenix, the Heian ox-cart wheel and fan, the Nara deer, all made their way into the weaving designs. Treasures from the 8th century Shoso-in yield designs for obi in every era, as do the motifs of the people in power: the Aoi-no-mon of the Shogun, the Kiku-no-mon from the Imperial family, not to forget the butterflies and diamonds from the family crests of lesser but still important clans.

For those interested in auspicious designs, there are pines both realistic and stylized (as in the kabuki costumes), cranes, masses of chrysanthemums, turtles and water for signs of life and longevity. (If your fengshui advisor suggests more water in your life, perhaps a water-motif zuan could do the trick without having actual bowls of liquid to overturn or grow icky?)

How modern and exuberant do the designs get? Well, if you love the graceful yet lively lines of some anime manga, or the modern feel of Japanese architecture, you are seeing works that draw on the same sources of tradition. The Tokugawa period was a time when the merchant class, unexplainably untaxed, flexed their economic resources to both gain status and have fun, and their descendants still do so (even now that they are taxed). The drawings done on walls and screens for the people of that era who had a certain amount of taste, a definite amount of money, and were free of any stifling status in the official order of things, are now worth millions of yen. The zuan are smaller in scale, but just as bold, some in a timeless way— silk cords tied in knots, done in bright flat comic-book colors, others are decidedly modern geometries with a 1920s feel.

It’s tempting to buy an obi, or kimono, to display in your home, but this can be problematic. Upkeep can be one of the problems; fabrics out in the open air collect dust and soot and need cleaning, and you can’t just pop them in the washing machine or send them to the dry cleaner. The sheer size means some difficulty in deciding how to display your treasures, as well. A framed work of art is safely and easily kept clean, dry and dusted, and is much easier to hang on the wall (or store, or ship, for that matter). The obi zuan give you the option of combining both the aesthetics of the kimono and obi, the ease of upkeep of a framed work of art, with affordability that is not found in the larger screens that the Godoy gallery usually handles.

George Godoy advises on the frame and matting for each zuan. For those designs meant to be woven in nearly transparent overlay fabric, he chooses a backing paper, often silver, that gives a sense of light and depth. The size of each zuan painting varies slightly, but is generally 33cm by 76cm-82cm. Framed, the works are large enough to be serious, yet small enough to move easily when you relocate (or, small enough to wrap and hand someone as a present.)

“What’s interesting about these are that they are very important, very powerful paintings,” says George Godoy. “They may be inlaid in gold and silver, you can see full pigments, and they may be embossed or moriage also, incorporating design elements of Japanese art. These are paintings that are almost always kept in-house, and as far as I have been able to find out over the past ten years, they are not released, or even shown to the general public. In fact if you go to the Silk Museum in Kyoto, you may see only two not very good examples hanging on display there. I first discovered these, I have a vast network of access to a lot of art, and among my contacts, I saw these and was very interested. I didn’t know what 1 was buying, and eventually I was told, well, these are designs for obi. And I thought, if I could get these and put them into frames. I was quite excited, they are completely transformed.”

“These actually lend themselves to Western interior decor. Themes — you can find almost anything. I have placed a few of these with the textile design museum in Germany, and I have talked with the Smithsonian as well.”

Godoy continues with a caution, “When the (Nishijin) companies realize they are not going to use these, they generally destroy them, so the designs will not fall into the hands of their competitors. Over a ten-year period I managed to acquire about 3,000, and each is an original, painted on silk or paper. Three thousand sounds like a lot, but they are not being produced these days.” The supply is limited. “When the 3,000 are gone, they are gone.”

George & Sandra Godoy Antique Japanese Screens & Fine Art is located at 5-30-10 Shimo-Meguro, Tokyo. Tel. 090-3688-8189.