by Charlotte Anderson & Gorazd Vilhar

Pilgrims travel far to reach Osore-zan. A place of awesome desolation where the spirits of the dead are thought to gather, people come to “Fear Mountain” in Aomori’s Shimokita Peninsula Quasi-National Park to touch the world beyond.

The misty caldera lake stands deep and still amid a barren volcanic plateau, and it is set against an often dark and brooding sky. From ancient times the Ainu people who once inhabited northern Honshu revered this otherworldly place, and the lake’s name, Usori, is closer in sound to the Ainu name than the Japanese Osore. The Buddhist temple Entsu-ji has watched over this remote and mystical place for more than a thousand years.

The bodhisattva Jizo is popularly worshiped in Japan as the saint-like protector of children and travelers. In this place O-Jizo-san is credited with coming to the aid of child-spirits in their efforts to journey to “die other side.” Pilgrims sometimes bring simple straw sandals, waraji, to leave for him as an offering, for it is seems that he wears out countless pairs on his endless benevolent treks over this harsh landscape.

A disheartening tale has Osore-zan’s child-spirits spending their days piling up mounds of stones and pebbles to serve as stepping stones across the water to reach the world beyond. At night demons are said to topple the piles, so the work and suffering of the little ones goes on and on. As an expression of pity, each visitor to the sacred mountain customarily adds a few stones to the piles.

The sandy shore of the lake is blanketed with little clusters of poignant offerings: candy, snacks and toys which would delight a child. Nearly every cluster is marked with a pinwheel which spins in the breeze, riffling the air with the softest of sounds. Parents come and stay a while, praying, remembering… Often they bring a picnic lunch which they eat right there, seated on the ground, sharing food and conversation with the spirit.

Here and there also lie great piles of offerings to adult spirits, obvious by the large quantities of whiskey, sake, beer and cigarettes among them. The giver might open the packaging of the food or drink, or even light a cigarette from an offered pack, to make it easier for the spirit to partake of the essence.

A graceful red bridge, representing a passageway to the world of the dead, stands at the edge of tine lake. Occasionally the elderly or the ill might come to rehearse the crossing, relieving apprehension of that inevitable time in the future when they will truly pass from this world of the living.

Closed for winter due to the heavy snow, the mountain is accessible only from mid-April until November. For three days this autumn (Oct. 11-13), Osore-zan will be crowded with pilgrims for its annual Aki Mairi. (Another similar event is held in summer.)

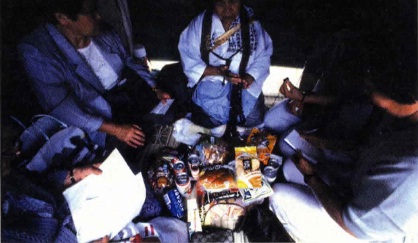

Blind female shamans called itako congregate here and through them people seek to make contact with their lost loved ones.

As a medium manipulates her prayer beads, strung of berries and interspersed with objects believed to possess supernatural powers—old coins, seashells, bear claws, stag horns, bird talons, boar tusks—she falls into a trance and summons the requisite spirit.

One young woman, for example, has come to give the happy news to her mother, whom she lost while a middle school student, that she has graduated from the university. A man getting up in years longs to tell his wife, whom he lost a few years before, that he will see her again soon on the “other side.” Osore-zan attracts people from all over the country, each with his or her own special reason for making the journey to this sacred place.

The dead, it seems, have much to say too, and visitors are eager for and moved by the messages transmitted to them through the mediums. The spirits may convey words of endearment or give comforting reassurance that they are fine in their otherworldly home. They may have advice for family members, sometimes reprimands, and even occasionally warnings of impending dangers.

But perhaps most often of all, they gently remind their descendants to not forget them, for in Japan it is not only the living who require attention and care. As long as they are properly remembered and honored, ancestors and other lost loved ones remain, in spirit, a vital part of the family circle.

GETTING THERE

You can now get from Tokyo to Hachinohe in just under three hours by Shinkansen. From there, take the Tohoku Honsen Line to Noheji Station (50 minutes) and change to the Ominato Line to Shimokita Station (one hour). From there it is 40 minutes by bus to Osore-zan. Note that there are only three buses that run each day. They leave at 9 and 11 a.m. and 2 p.m. By air it is just one hour and 10 minutes from Tokyo (Haneda) toAomori.