by Charlotte Anderson & Gorazd Vilhar

For time immemorial, all over Japan, mountains have been deemed the abodes of the gods, the kami. Kyoto’s Inari Mountain is thought to have been a site of animist worship since the 6th century, even before the city itself was founded as the capital Heiankyo in the 8th century.

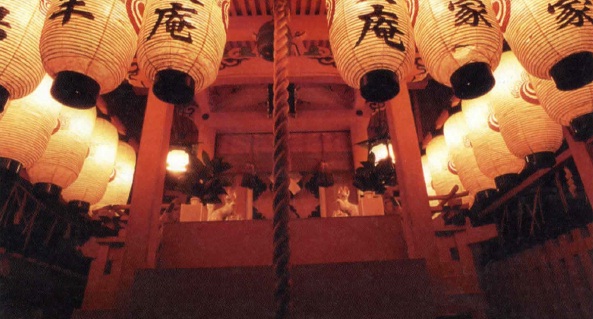

Of course the mountain was a remote wilderness then. All these centuries later it’s a part of the city itself. Sprawling over the mountain slope is Fushimi Inari Taisha, an ancient and immensely popular Shinto shrine — a spiritual center for some 30,000 Inari shrines throughout Japan. The shrine approach is lined with shops and restaurants catering to the millions of worshipers who make pilgrimages here to worship Inari, Japan’s traditional deity of rice as well as contemporary deity of commerce.

For centuries before the city encompassed this area, rice was farmed on all the flat land around the mountain. Sparrows were the bane of farmers, coming as they would to eat the ripe rice grains, so they were captured and added to a somewhat meager peasant diet.

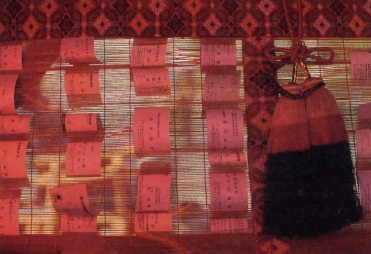

Still today these birds are skewered and grilled, along with quail, at the small and simple old restaurant, Inafuku, which stands just before the entrance to the shrine. Arriving in time for an early lunch, we feel like cats as we crunch the tiny bones of these bitty and tasty birds before heading off into the shrine precincts. Perhaps there is no better place to see the efficient Japanese fusion of religion, folk beliefs and commerce than at this place which enshrines the patron deity of much of the Japanese working population. Dozens of kinds of amulets and talismans are displayed and sold at shrine stalls.

Halls accommodate many worshipers at a time for personal purification ceremonies believed to bring good health and good fortune. Businessmen travel from all over Japan to receive blessings at this shrine, especially at the New Year when they pray for a successful business year ahead, but also when a particularly important business deal hangs in the balance.

Snaking their way up and around the wooded mountain are tunnels consisting of thousands of Shinto archways called torii, each one purchased at considerable cost, inscribed with the name of the donor — individual, family or corporation — and installed as offerings to Inari-san. These winding passageways lead to countless small shrines, wayside altars and private lay worship stones called otsuka, scattered over the mountainside.

Worshipers and wanderers are numerous, and the atmosphere can often be highly mystical, with the light of smoking candles and the sounds of incantational prayers. Miniature wooden torii are piled high, symbolic offerings for those of more modest purses or prayers.

Grains of rice, cups of sake, and figures of the deity’s fox messenger are offered on every altar, often with fried tofu which is said to be foxes’ favorite food. Fox spirits may partake of the essence, but the food itself is sometimes snatched away by hungry cats or an occasional tramp.

If one has passed up the chance to purchase an amulet or prayer plaque at the main shrine stalls below, other opportunities present themselves here and there on the mountainside. At one spot it is even possible to purchase small pouches of sacred sand which can be carried home to scatter over and purify one’s own little patch of land.

Nearing the mountaintop, the panorama of modern Kyoto in the valley below reveals itself. We stop at a little restaurant for a rest and a fortifying bowl of soba noodles before continuing the climb to the very top. There we come upon a deceptively artless but spiritually-resonant scene: a mirror set upon stones to reflect the amazing sky above.