by Corky Alexander

Long way from The Apple, Hermosa Beach, Basin Street or New Orleans, plethora of fine jazzmen (and gals) have found their niche in jammin’ Japan.

Between the end of World War I— “The War to End All Wars”—and the beginning of World War II— “Just Kidding!”—there was a veritable exodus of fine jazz musicians fleeing America for Europe where they found respect and a love for their music exceeding anything to be found at home. The jazzers, mostly black, learned that in the Continental environment the color of their skins took a back seat to the admiration European fans felt for the superb brand of music played.

The trend continued following the cessation of hostilities after the battle for Europe and the Orient had been won by the good guys.

Such legendary “colored” players as soprano saxman Sidney Bechet, drummer Kenny “Klook” Clarke, be-bop pianist Bud Powell, tenor players James Moody, Don Byas, Sonny Rollins, Lucky Thompson and Dexter Gordon, trumpeter Bill Coleman and many, many others. They found surcease in Paris and Stockholm, mainly, as did white musicians such as clarinetist Tony Scott and bassman Red Mitchell. In fact, Sidney Bechet died in Paris in 1959, a virtual national treasure of France, on a par with the fabulously popular risque showgirl Josephine Baker.

In similar fashion, scores of top-notch American jazzmen have fled the U.S. for Japan where the general population seems to have a respect and love for jazz music that puts to shame the sometimes ennui demonstrated by American music listeners.

Jazz came to the Orient—largely Japan and Shanghai— in the Roaring ’20s when flappers and voh-do-de-o-do licks were all the rage. In post-War years, Norman Granz’s Jazz at the Philharmonic invaded Japan’s shores and things never have quite been the same since.

It’s not that racism doesn’t exist in Japan; we all know that it surely does— and that goes for Caucasians, to a lesser degree, as well as black players. But perhaps it is not quite as humiliating or pervasive as in some segments of the U.S. And at any rate, there is ample work for good jazz musicians in the Tokyo atmosphere to keep a player busy and productive.

It’s the purpose of this article to describe and illustrate the quality and musical horsepower possessed by some of the musicians living and working in the Tokyo-Yokohama area. Please note that this story will by no means cover all the excellent musicians making their living here; it was almost impossible to run them all down for this piece. But those profiled herein are perhaps typical of the guys and girls who’ve come to Dai Nippon to play and live in the sometimes perplexing and topsy-turvy world that is Japan.

Among our merry band of jazzers here are guys who have played in some of the best, most renown of the big bands during the heyday of such organizations. Drummer Tommy Campbell, for example, played for three years with Dizzy Gillespie’s band; trumpeter Mike Price played trumpet and Flugel horn with Stan Kenton, Buddy Rich, Gerald Wilson and other aggregations that featured hard-blowing, ball-busting brass sections. He currently is the “token gaijin” in the trumpet section of Japan’s best big band, Nobuo Hara’s Sharps & Flats.

A spirit of camaraderie and pulling together runs rampant through this small but eclectic jazz community.

So, we boast a close-knit, tight clique of great players helping one another and playing great music. Let’s take a look at a sampling—surely not all! —of Tokyo’s gaijin jazz family.

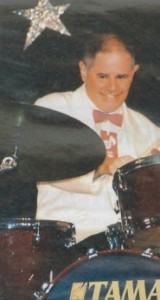

I suppose the senior guy here, in terms of longevity in Japan, would be drummer Mike Reznikoff, who first arrived here in 1967 in uniform, playing with the 296th U.S. Army Band, stationed at Camp Zama.

He told me that, “I found out, among other things, how much people here love jazz.”

Discharged in 1969, Mike returned to his home in New York, hoping to play straight-ahead jazz, but ran head-on into the fusion (which he calls “confusion”) phenomenon. Forced into playing music he didn’t like, he eventually found the going so tough that he decided to return to Japan in 1977, a move he’s never regretted.

“It’s ironic, I guess,” he says, “but I’ve had opportunities to enjoy great musical experience I’d never have had if I’d stayed in New York.” He recorded on about 15 albums during that time, a few with another Tokyo ex-pat, the late pianist Don Abney, and all-time bass great Red Mitchell. He’s also got a regular gig twice a week drumming behind Yoshio Toyama’s Dixie group at Tokyo Disneyland.

Summing up, Mike says, “The spirits have been very, very nice to me. I’m very thankful for the life I’m living as a jazz musician in Japan.”

Trumpeter Rick Overton is an educator as well as a splendid jazz player. Not so long ago, he left Nishimachi International School where he’d taught the elements of music to youngsters since 1993. He now is Assistant Professor of Jazz Improvisation at Tokyo College of Music.

“Raised in New York and a graduate of Berklee School of Music in Boston, Rick was heavily influenced by jazz legend Miles Davis and the concept of ‘music on the edge’ in which artists weren’t afraid to push their playing and compositions beyond what was accepted,” according to local writer John Montgomery.

Working with equally legendary producer Teo Macero, Rick learned the tricks

of the musical trade, including, according to Montgomery, “how to keep from taking himself too seriously.”

Feeling the need to take a break from the tensions of the frenetic New York scene, he made his way to Japan, accepting an invitation to come and do some arranging and playing freelance gigs. He planned on giving this trip maybe 18 months, but something happened: he fell in love and married. He and his wife Hiromi, a counsellor at Temple University, have two sons, Eric and Sean.

Following his first solo CD in Japan— Tokyo Time Zone—he released his second entitled Urbanesque, featuring aforementioned drummer Tommy Campbell, Rick Stark on piano and Shinobo Sato on bass. Each of the eight compositions on the CD is an original by Rick Overton. According to Stark, “Each of Rick’s compositions provided a forum in which all of us could converse, respond and create.”

Staying in the horn section, we shall now consider the huge talent and organizational genius of one Mike Price. Mike came to Japan in 1989 after being offered an artist-exchange fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts and the U.S.-Japan Friendship Commission.

This was after an extensive education earning music degrees from Northwestern University, Berklee College of Music in Boston, a Masters Degree from the University of Southern California, study of ethnomusicology at UCLA—not to mention massive studies in the Japanese language in several institutions. He had five years of personal study with Vincent Cichowocz, trumpeter with the Chicago Symphony. This man can really play!

In 1964, Mike toured Europe as part of the Tex Benecke Glenn Miller Ork; played first chair trumpet with Stan Kenton, ’67-’68; short tour with the Harry James outfit; with Buddy Rich as first trumpet; played with the Toshiko Akiyoshi-Lew Tabakin touring band, visiting Japan six times; toured California with the excellent Gerald Wilson big band.

In Japan, Mike joined the Nobuo Hara Sharps 8c Flats ork in the solo trumpet chair in 1990 and still is with this fine aggregation. In ’93, he formed the Mike Price Jazz Quintet, later his big band, a 16-piece go-group that performs such complicated and taxing pieces as Duke Ellington’s Shakespearean suite “Such Sweet Thunder.”

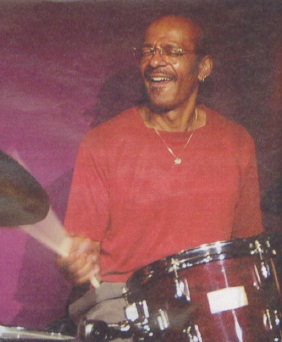

Now, let’s take a peek at Tommy Campbell, a hard-driving yet tastefully elegant drumming man. Growing up outside of Philadelphia—a hotbed of great jazz musicians—Tommy was raised in a musical environment. His father was an organist and singer and his uncle is Jimmy Smith, the renowned Hammond B-3 genius. Tommy recalls, “I was surrounded by music and drummers from the time I was a little kid. My father and Mickey Roker would rehearse at the house a lot and whenever Uncle Jimmy had a new record, he’d come over with a copy. We’d listen to it and I’d play along for hours.”

As with so many fine musicians, Tommy is a graduate of the Berklee School of Music.

As mentioned, Tommy played with Dizzy’s big band, and also with Sonny Rollins, John McLaughlin, The Manhattan Transfer (alongside Tokyo’s Mike Price), Kevin Eubanks, his uncle Jimmy, Stanley Jordan, Charlie Mingus, Tania Maria, Gary Burton and a host of other jazz giants.

Other Tokyo jazzers tell me they love playing with Tommy back on his kit behind them. He lives here with his wife Jessie and has legions of friends around the world.

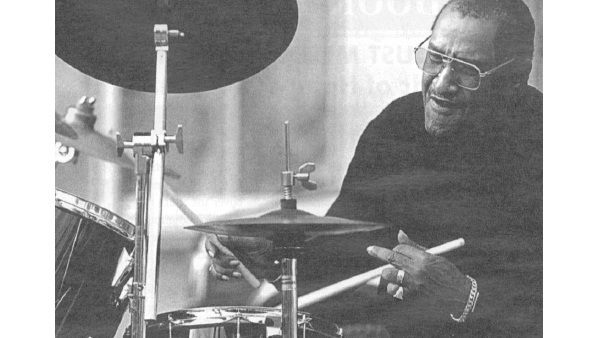

Also reigning from behind his impressive array of drums and cymbals, we find massive Jimmie Smith, a powerhouse of drive and a great timekeeper along with the dynamics. When he’s not out at Tokyo Disneyland drumming as a regular with the fine band out there, he can be found in any number of jazz venues.

A native of Newark, New Jersey, James Howard Smith studied at the Germansky School for Drummers and later at the Julliard School. In New York, he recorded with such top-flight dudes as Pony Poindexter, Jimmy Witherspoon and Gildo Mahones; performed and recorded with Lambert, Hendricks and Ross, appearing with those vocalese wonders at the famed Newport Jazz Festival.

He toured and recorded with Erroll Garner, Benny Carter, Bill Henderson, Hank Jones and Harry (Sweets) Edison. He later recorded with Sweets and Eddie “Lockjaw” Davis. According to The New Grove Dictionary of Jazz, Jimmie “has been much sought after as a sideman owing to his clear, crisp sound and his reliable sense of swing.”

If you’d like to run into the affable, outgoing Jimmy Smith, maybe you should fall by his own saloon, Lupin, located in Roppongi. Tel: 3403-9828. He’ll make you at home.

Staying with the drummers, we can’t forget Forris Fulford, a veteran player and a longtime Japan hand who, like Jimmie, Mike and Tommy, works constantly with a wide variety of groups. A smooth swinger, Forris was born in Brooklyn and began playing drums at Boys High School at the age of 16.

Forris served in the U.S. Army Band for 20 years, sometimes as an instructor at the Armed Forces School of Music. With the 76th Army Band in Kaiserslautern, Germany, he toured throughout Europe. Later he was assigned to Camp Zama with the 296th Army Band.

Forris still lives in the Zama area where his wife teaches at the DOD School out there. A very tasteful drummer whose musicality and finesse always contribute to a greater effect of the group with which he’s playing.

Another most excellent drummer around town is Cecil Monroe who stays busy with frequent gigs. Sorry, but I was unable to contact him for this article. Dynamic gent named Babe Hanna has been knocking on his conga drums and contributing creative dance to the music scene in Tokyo for a long, long time. A free spirit loaded with charisma, Babe now has his son joining him on the local music circuit. A great guy!

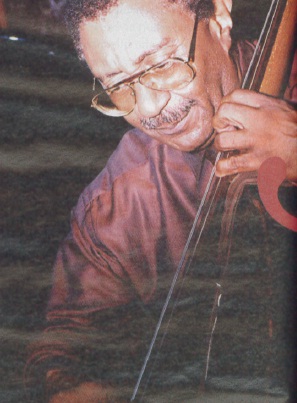

Remaining in the rhythm section, we will now consider a pair of most talented bass players.

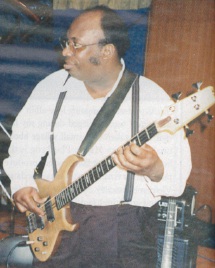

Paul Jackson has been playing bass since he was 9 years old, considered by his teachers a musical prodigy. Born in Oakland, he played in the local symphony orchestra when he was just 14, the same year he expanded his musical exploration to include bassoon and piano.

Paul later studied with the San Francisco Conservatory of Music which eventually led him into teaching seminars for years with such Tokyo institutions as A.N. Contemporary Music, Pan School of Music and the Musashino School of Music and later at Berklee School of Music, the University of California at Santa Cruz and San Jose State among others.

Known as a “musician’s musician,” Paul was a founding member of the famed Headhunters alongside pianist Herbie Hancock.

In Japan, Paul embarked on a solo recording venture, releasing his own album Black Octopus on Toshiba EMI Records. His compositions have earned him Grammy nominations in 1974, ’75 and ’76 for writing “Chameleon,” “Hang Up Your Hangups” and “Spider,” respectively. He’s also played on movie soundtracks for such hits as “Deathwish” and “Dirty Harry“; spent 18 months with Radio Free Europe.

Paul Jackson has lived in Japan since 1985 and is most active in the musical community, playing both “stand up” string bass and its electronic cousin. In 1986, he began his popular “Jazz for Kids,” a cultural program aimed at school-aged Japanese children calculated to introduce black culture and music via music, dance, narration and slide presentations. More than 100 schools across the land have enjoyed Paul’s Jazz for Kids and its documentary produced by Japan’s Ministry of Education in 1991.

In fact, he was awarded the key to the city in a couple of communities in gratitude for his contributions to mutual understanding and in bringing America’s ethnic music—jazz— into the forefront.

He currently has two CDs featuring the Bad Boys Blues Band on the market, doing well. A massive giant of a man, he is filled with good cheer and a necessity to laugh aloud a lot.

Stan Gilbert is one of the best guys I’ve ever known, and it’s a pleasure to call him friend. And play the bass? Man, he is a bloody virtuoso on the string bass.

Holding forth in Akasaka’s Club Kei, subtitled “Jazz and Bossa Nova Club,” Stan, as musical director, has played with top-notch musicians from around Japan and over the globe. He is head of KS Entertainment International Ltd., licensed to promote and produce international event tours and productions since 1995.

Under these auspices, Stan has brought over to Japan such talents as Slide Hampton, Jerome Richardson, Lew Tabakin, Kenny Burrell, Teddy Edwards, Ernie Watts, Vaughn Klugh, Vince Herring, Don and Alicia Cunningham, Hubert Laws and Llew Matthews. Dropping by from time to time are such luminaries as Hank Jones, Diane Reeves, Jimmy Scott and Freddy Hubbard.

Working hand in glove with bossa nova vocalist Kei Ishida, Stan has made Club Kei a must-stop for visiting jazzers. New York-born Stan has a number of fine CDs on the shelves of top stores round the world, one dedicated to his parents who come from St. Kitts.

His latest CD, Beauty and the Beast (a duo with pianist Michiko Tatsuno) showcases some great tunes, including a Stan Gilbert solo on “Ave Maria.” The liner notes are spectacular, written by me.

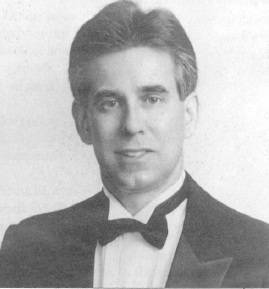

Magnificent keyboard artists grace our local jazz scene, notably Jonathan Katz and Tom Pierson.

Jonathan leads his own fine combo—Candella—which plays almost constantly in the Tokyo area. Jonathan doubles on French horn.

Born into a musical family, Jonathan began playing piano at 5 and French horn at 9. He discovered jazz in high school and played as a teen with Frank Foster. At Yale University, he gained valuable experience playing in the symphony, jazz ensemble, musicals and much chamber music. He first saw Japan on a Yale orchestra tour, which sparked his interest.

He graduated from Yale with a degree in classical music, whereupon he came to Tokyo for a year of intensive study in the language. He returned to the U.S. in 1989 to earn his masters degree in Jazz and Contemporary Media from the Eastman School of Music.

He returned two years later to master the language and follow his musical grail. An erudite figure in Tokyo’s musical milieu.

The great jazz master Gil Evans called Tom Pierson “the best unknown composer I know.” Similar rave reviews from critics over the world have buoyed Pierson to a certain pinnacle of excellence. As a young piano prodigy, Tom was soloist with the Houston Symphony at age 13. Later he studied at Julliard in New York and afterwards conducted Leonard Bernstein’s “Mass” at the Metropolitan Opera and scored films for director Robert Altman.

He also gathered his own orchestra and accumulated some of the world’s finest musicians in his group.

He moved to Japan to escape New York violence; he’d been a victim of crime seven times.

Here he performs with many groups and toured as a member of Kenny Burrell’s quartet. He recently released a two-set CD enigmatically entitled Left and Right, backed by bassist Toru Kase and drummer Pheeroah akLaff. It is a fascinating “listen” which requires concentration.

Let us now consider musicians with “other” instruments. By that I specifically mean the shakuhachi. John (Kaizan) Neptune is a jazz player of another ilk, in that he blows into a bamboo stalk and makes delightful, otherworldly sounds. He plays shakuhachi, the four-hole (three on top, one on bottom) shaft of tree root that creates a mournful, haunting sound. Except this displaced Californian makes terrific jazz music with his stick. No reed, you see: just a carved niche through which he blows.

John left his La Jolla, California, home bound for Hawaii where the surfing was better. There at the university, he elected for ethnomusicology, zeroing in on shakuhachi. This led him to Kyoto where he stud-ied for five years with a master teacher until he got his own “master” rating. Since that time, he’s lived in the bucolic country-side outside Tokyo, amassing a group of musicians playing exotic instruments from throughout Asia.

They tour, record and perform to ever-greater acclaim. Though he also plays classical Japanese music, jazz is his forte.

Pamela MacCarthy is a “girl singer” with jazz instilled in her very soul. From upstate New York, she began singing out of school, which took her to the wicked city. Singing in small clubs, one night she met a fine tenor player from Japan, Akio Ueda. Sparks flew and they were married.

This was about 15 years ago; they have a terrific son, but the marriage got into trouble and they split, though still married. Akio backed up Pam’s voice for some years, but she’s on her own now and sounding better than ever. She’s got a new book featuring vintage Billie Holiday and Carmen MacRae songs, which she gives great treatment. Her popular CD entitled How About You is comprised of mostly Gershwin tunes.

Pam MacCarthy is a fine example of how a musician improves along the way—she’s better than ever.

And, of course, our own Dolly Baker just recently left Japan after around 35 years of singing and entertaining generations of gaijin who’ve made their home in Asia. I wrote a long Page 1 tribute to her upon her departure, but the musical world of Japan misses her still.

She’s happily ensconced in her own apartment in Brookline, Massachusetts, where she still performs on a regular basis at the age of 80. The Unsinkable Dolly Bee!

Although not a fulltime Japan resident—though damned near—pianist-vocalist Ora Reed has amassed an enthusiastic following among local gaijin and Japanese alike. For the past five or so years, Ora has divvied up her time between Japan and the States, three months here, three months there. She performs at the elegant cocktail bars and salons in some of the leading hotels in Japan, originally in the Westin in Ebisu.

Currently she is playing and singing to delighted crowds in the Kyoto Takaragaike Prince Hotel, making new friends daily. Classically trained, the Mississippi native first appeared in gospel groups back home and played and sang church music while learning the vast vocabulary of modern pop and jazz tunes.

For a time, she was the piano accompanist to such operatic luminaries as Leontyne Price. Her repertoire ranges from light jazz tunes to middle-of-the-road melodies inspired by Sinatra and Nat (King) Cole. A delightful addition to our musical entourage.

Other excellent singers abound, such as Nathan Ingram and Alex Easley, neither of whom I could contact for this article. Also busy working in sessions (and in the Mike Price band) are two fine trombonists, Fred Simmons and Don Gibson. Plus bassist Mark Tourian and drummer Scott Latham.

As written, this is far from a complete rundown of all the fine gaijin musicians working and blowing here, but it was fun tracking these down and listening to their stories.

Horns up!