by Shirley Booth

The annual season of over-indulgence has come to a close. Too much fat, too much sugar and too much alcohol has left many of us with the usual determination to improve our diets. New Year’s resolutions are being made all over the country to “cut down” and take more exercise.

Cutting down, though, can be difficult if you stay within the confines of a typical western diet. Substitutes for bacon and cream, however hard the alternative foodies try to convince us, just aren’t the same as the Real Thing. Tofu ice cream is OK, but it’s not a patch on Haagen Daz. Secretly, we all know that.

The answer, then, is to try a completely new approach. Living in Japan is the perfect opportunity to try to embrace an eating pattern where temptations of ice cream traditionally, at least, don’t exist, and can be ignored. Turn a blind eye to the familiar ice cream shops crowded with spotty young schoolgirls—they can ruin their skins if they like, poor things—and start looking at the Other Japan. Forget Kinokuniya and take a walk around a regular Japanese store, the local neighborhood mom-and-pop shop down one of the charming little ginzas; or even the food basements in large department stores.

These food basements are treasure troves of delicacies waiting to be discovered. Walk around and try samples. If your Japanese is good enough, ask questions. “What is it?” “How do you eat it?” You don’t have to just wonder what those pickled Things are, those dried God-knows-what. Find out what they are and how to eat them, and they could be the key to a whole new way of eating and living.

The Japanese have been eating a low-fat, low-protein diet for centuries. Only since the war have they begun to adopt a more westernized diet, high in animal fat, white sugar and white flour.

It was only 140 years ago that the general populace were allowed to eat meat. Buddhist belief forbade it until contact with Westerners convinced the emperor of the time that meat eating was a Good Thing. So convinced was he, that the public was not merely allowed, but instructed, to eat meat. Those pious souls still resisting were told that they were slowing down the pace of civilization.

Thus began an era of hamburgers, hot dogs, cookies, cakes—and with it a rise in heart disease, diabetes and breast cancer. Not to mention obesity and spotty faces.

In the temples, though, things carried on as before, and still do. The true faithful didn’t even eat fish, as the killing of any living creature could mean you would be re-born as cattle in the next life. Protein came from the humble soy bean—the Chinese call it “the meat of the fields.” Not that you would always recognize it as a bean. Tofu, miso, natto and soy sauce are its most well-known guises. Sea vegetables and sesame provided calcium and flavor. Other flavors came from such things as the ubiquitous umeboshi plum; the yuzu, a fragrant citrus fruit unique to Japan, and, of course, ginger.

But people in the temples didn’t mind enjoying their food—it was a gift from God, after all—though not given to long evenings getting blind drunk on sake like the rest of the populace, they used plenty of it in the kitchen.

These days many of the Japanese themselves, especially the younger ones, think all this kind of thing terribly un-modern and un-western. But most of you are western anyway, you don’t have to prove how western you are by killing yourselves with a lousy diet. No, you live in Japan. You can study ikebana and try being Japanese, or kanji, or pottery or tea ceremony. But the best thing you can take home with you when you leave, or practice while you are here, is a new way of eating. You can do your bit to preserve Japanese tradition, and your body at the same time, by learning to eat the old Japanese way.

“How?” you ask.

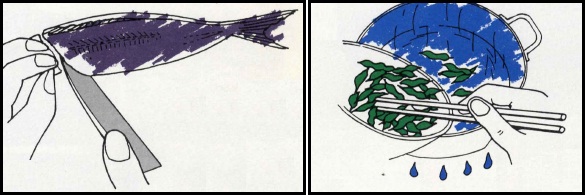

Forget the meat, and substitute with fish. Cook it the Japanese way, lightly broiled. No preparation, no sauces to fiddle with, just stick it under the flame. That way you’ll get to understand the flavor of fish. Eat it with rice instead of potatoes dripping in butter. If you can’t make the immediate jump to the infamous hippie standby, brown rice, then try rice with at least the germ left in. It’s called haigamai in Japanese. Maybe you’ll eventually get a taste for the honmono, husks and all, called genmai. Your local rice shop will sell it to you, but they may have to fish around in the back of the store to find it. Let them.

Some of those funny little packages in the fried-food section of the Japanese store contain Things to sprinkle on the rice, such as furikake which is a mixture of dried seaweed, sesame and dried fish flakes. Edo-murasaki is a paste of nori (laver sea vegetable) and soy sauce, and it’s eaten spread on top of rice. Just a smidgeon is enough.

If you can speak some Japanese, have a go at asking the advice of the assistants in the shop, they can uncover all kinds of mysteries, and it’s a fun way to learn. Most of them are past 30 so they know what they’re talking about!

A very simple idea for serving green veggies, such as spinach, which you can try right away, is to steam or boil lightly, for 30 seconds. In the temple tradition they eat the pink roots too, as one of the basic principles of temple or shojin cooking, is that nothing should be wasted. Just wash well first. Then serve with a dressing of ground sesame seeds mixed with a little soy sauce and sake. Or sesame and sweet miso (called saikyo miso). Even simpler is to just sprinkle kiatsuobushi (dried bonito flakes) on top, and serve with soy sauce. The sesame and miso dressing, mixed with sake, also goes well with root vegetables such as turnip. When you’ve done these things yourself just once you’ll realize how quick and easy the traditional Japanese way of eating can be, and you’ll start getting ideas of your own. Also, as a lot of food is served at room temperature it can be prepared in advance.

You can also try using Japanese ingredients in a Western way. A delicious cholesterol-free salad dressing can be made with umeboshi paste (mashed up umeboshi plums, called bainiku). Mix two and a half tablespoons of the paste with one cup of soymilk (tonyu), four teaspoons of sesame oil and one teaspoon of rice vinegar (mild and smooth). It’s just as creamy as the island variety, but not cloyingly sweet.

Sweet white miso has a mild, less salty taste than regular miso, so it too lends itself to dressing. And it’s a good source of protein. You can mix it with soy milk and vinegar, or sake or even water, then add flavorings such as mustard, ginger juice or chopped perilla (shiso) leaves. Once you get the idea your creativity is the limit.

Fortunately some very dedicated people have written some excellent books to help you in your new adventure. There are plenty of books on how to cook the kind of Japanese food you are used to eating here, such as tonkatsu, agedashi dofu, etc. Better Homes publishes one that is easy to understand with lots of nice pictures.

Step by Step Japanese Cookery, by Lesley Downer and Minora Yoneda is good too, with explanatory pictures. These books also include Japanese meat dishes.

Japan Publications has a range of books which are more strictly vegetarian, and which also contain recipes using Japanese ingredients in a more Western style. The Book of Miso, by Bill and Akiko Shurtleff, is one of the most thorough and well researched books I have ever read on a food. It contains more than 400 recipe ideas, and fascinating background on the history and production of miso.

Cooking with Sea Vegetables (pub. Thorsons), by Peter and Montse Bradford, has lots of Japanese and Western ideas of what to do with all those mounds of seaweeds you can find piled in the stores. Have a browse in Kinokuniya or Maruzen and find what you think will suit you the best.

But if you want to tap the tradition at its source, and learn about temple cookery, called shojin, with no fish and no dairy products, then treat yourself to The Heart of Zen Cuisine, published by Kodansha. It was written by the abbess of Sanko-In Temple in Musashi Koganei, who herself is an excellent shojin cook. There is fascinating background on temple beliefs about food, and the abbess is more than willing to share her temple’s 600-year-old secrets with us in this book.

A word of warning: some of the cookbooks on the market, including the abbess’ I have to add, suggest the use of sugar in nearly everything. You don’t have to use it. In fact I recommend that you don’t, as the natural flavor of the ingredients will come through even more and, as you get used to those natural flavors, your desire for rich, sweet things will fade away. Without even suffering you’ll find you’ve “improved your diet.” And you’ll be helping Japan to keep alive an ancient and disappearing tradition too!