by Denny Sargent

On Feb. 3, some of the “devils” that supposedly caper about us unseen suddenly become visible in Japan. Not only do they show themselves, but they can be observed fleeing for their lives from bean-throwing children in almost every house and apartment in the country, from Hokkaido to Kyushu.

This day is Setsubun (“the parting of the seasons”), the festival that marks the end of winter and the beginning of spring. These “devils,” actually called oni, can be seen scampering about, being pelted with roasted soybeans, are often the fathers or mothers of each household. Though on the surface the entire drama is quite hilarious, there is a deeper magic behind it.

The oni is a spirit who resembles the Western Devil greatly in that he has horns and a lecherous leer, but in Japanese mythology oni are not always evil; just mischievous. There are all kinds of oni, most with horns, tigerlike loin cloths, clubs and elfin satyr-like faces. They are said to live in the wilderness and can help or harm, depending on their mood.

Two particular oni are associated with the hardships and nasty weather of winter. They are aka-oni (red оnі) and ao-oni (blue oni). They may have some connection with the Nio-sama, the “thunder god and wind god” that can always be seen on either side of gates guarding temples across Japan; no one can be sure. What is sure is that when dad puts on the aka-oni mask, he represents all the problems and evils of the winter and the sooner he is chased out of the house, the better.

This is done by family members tossing soybeans at him (and into all the rooms of the house) while yelling, “Oni wa soto, Fuku wa uchi!” Roughly translated, this means, “Go out devils, come in good luck.” The next day is considered the first day of spring in Japan, so it is magically important to thoroughly cast out the winter demons.

After this bean-throwing ritual called mame-make, each person eats the number of his or her age in beans from the pile that is left. As, for example, a 10-year-old child eats 10 beans, she also absorbs good luck and guarantees her health for the year, or so the legend tells us. After this the house is thoroughly cleaned of dirt—and beans—and made ready for spring.

On Setsubun many families hang a hiragi over their doorway. This is a charm made of a piece of holly and a small fish tied together. The idea behind it is this: oni love dried fish, / so when they see it, they grab at it, but the sharp leaves of the holly wound them and send them running off in pain!

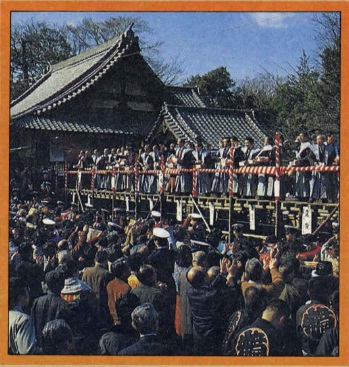

Setsubun is a great time to visit your local shrine and watch a more spectacular version of the private household mame-make ritual. Gojo Tenjinsha Shrine, in Ueno Park (among other shrines and temples), is the site of wonderfully theatrical version of the rite. Frequently, famed show business personalities or Sumo wrestlers throw the mame to the crowd at shrines.

The red and blue oni, looking really wild, suddenly attack the shrine. After scattering the crowd with great roars and the shaking of rattles, they begin to climb the stairs. Suddenly, the masked figure of the god of the shrine appears out of the shadows. A great battle ensues and, finally, the oni are driven off by the victorious god and by a shower of beans thrown by a collection of prominent people who have the honor of being in the shrine for the festival.

The god then sits on a throne while the priest enters and blesses everyone with a deeply intoned prayer. Following that, the dignitaries come forth and throw bags of lucky beans and toys to the crowd.

The mame-make ritual also takes place in schools. The oni is sometimes the teacher, sometimes a popular (or very unpopular) student. Later, the students are treated to a special serving of dried beans with lunch!

In the beginning of February, why not get into the mame-make act and celebrate Setsubun? Visit a shrine and watch the fun, or lure some unsuspecting friend or relative to put on an oni mask and chase him or her out of the house with wild shouts and flying beans. Happy Japanese spring!