by Fred Harris

Looking at Chinese and Japanese landscape painting

Being products of a western cultural heritage, and addressing most Asian art as exotic artifacts, the average foreign visitor to the Orient has difficulty in adjusting his viewing lenses to correctly focus on the profound world of art which abundantly avails itself to him.

Items such as scrolls, screens, dishes, etc. are commonly discussed as interesting mementos to be coveted while living in this part of the world. It is only a short step to lake to find out that these different artifacts are actually examples of serious art forms which have been around, in some cases, for hundreds of years. That, in fact, the general term “screen” is actually a large picture which folds, and “scrolls” are long pictures which roll.

These different forms represent one school of painting amongst many. Even within each school there are numerous avenues of thought which are quite comparable to any area in European art history. Our lack of interest in specifics related to Japanese and Chinese art is not unique. The same conditions exist with the Oriental person, even artists who are more adjusted to visual imagery have difficulty escaping binding conventions.

The average person looking at Chinese painting would have a difficult time viewing an exhibition of the 17th century “Individualists.” These works at first glance do not seem very different from the more familiar classic landscapes of the Sung Dynasty.

What makes the 17th century so different? An equivalent response can be made by a Chinese artist walking through galleries containing western works ranging from Italian primitives to Picasso and complain of stylistic similarities. As well as a neglect of proper brush work, which to the Chinese artist is one of the most important elements.

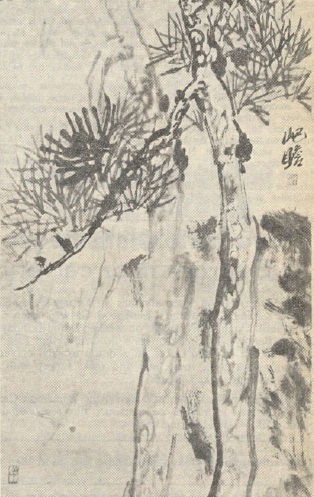

The modern viewer should become acquainted with the multiple trends within each artist. Chinese and Japanese art is concerned with revealing universal aspects of nature, not transient phenomena. It strives to reach an inner essence, not outer forms. That is why the sketchbooks of these masters delve so deeply into the structure of the simplist form such as a leaf — drawing it in a most realistic manner.

The fullest understanding of the object will be reached before painting it in line with distinct direct brushstrokes. In copying or imitating the past this art form places little premium on originality, compared to the attempt to contain some measure of truth. To quote a famous Chinese painter of the Ming period, “If it is beautiful scenery you want, go to nature; if it’s painting you seek, come to me.”

We must remember that Chinese landscape painting was rarely a visual report on any particular scene but composed in the studio. Landscape as the construction of the mind is not quite the same as a view that is fully developed on the scene. The idea of an order in nature is the aim of the artist.

A little reading on the subject from the mountains of books available—and a trip or two to the more than 30 museums in this city—will eventually open your mind to this most fascinating subject. Perhaps even elevating the novice to a level higher than “I wouldn’t mind buying a scroll.”