by Rick Kennedy

A walk through Old Tokyo

In Japanese terms, Tokyo isn’t an old city at all. It’s only about as old as Boston. And because twice in this century it has been all but obliterated—once by the Great Kanto earthquake in 1923 and once by the firebombing of 1945 which left standing only one building in ten—and also because a hefty percentage of the people who live in the city were not born here, there are few sections of Tokyo that evoke in anyone a nostalgia for things past.

Any Tokyoite will tell you, however, that the adjoining neighborhoods of Sendagi, Nezu and Yanaka near Ueno are the best places to go to get a sense of how things used to be, and it is to this part of the city that young scholars from Stanford and the Sorbonne come to rent old houses with a rock garden while they put the finishing touches on their dissertation on Kafu the Scribbler or the Staging of the Noh Drama.

They find here the essential coziness of the old style of Japanese urban living, with a lively street life, public baths that serve as neighborhood social clubs and shopkeepers who make a habit of setting aside something for their best customers, which is anybody who has ever dropped by twice. Sendagi, Nezu and Yanaka make up the core of shitamachi Tokyo.

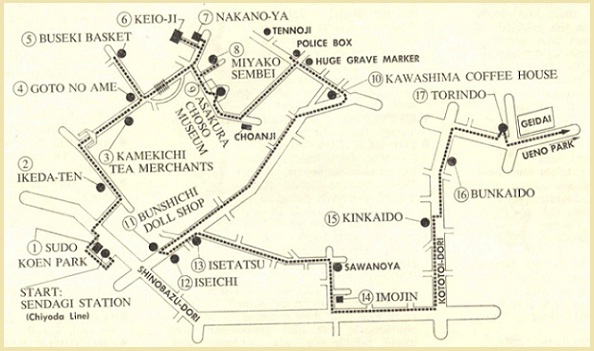

This walk through the area can take as long as seven hours, depending on how good you are at lingering and on how contemplative a mood you are in. Even if you take me up on most of my recommendations, the day should cost no more than ¥5,000. Note that if you take the walk on a Monday or Friday, you won’t be able to get into the Asakura Choso Museum, which is closed on those days. This would be a great pity.

Go to Sendagi Station on the Chiyoda Line. If you are coming from the direction of Hibiya, as you probably will be, sit near the front of the train so when you get off you’ll be near the Dokanyama exit, by which exit leave the station. This will put you on Shinobazu-dori the area’s main street. Turn right on Shinobazu-dori, then immediately turn right again into a narrow alley just after the Red Ai Coffee Shop. At the end of the alley is

1. Sudo Koen Park

Tokyo has more than 7,000 parks, ranging from the rolling Shinjukugyoen to pocket parks just big enough for a single bench. Sudo Koen is a medium-size park taken absolutely for granted by the people of the neighborhood who come here to cat lunch, watch the children play and don off. It is a very Tokyo sort of park, with its landscaping all out of scale with the size of the park (it tries hard to make you think it is bigger than it is), its dusty pool of carp and its vermilion Shinto shrine on a little island.

Cross the red bridge and walk around the shrine past the waterfall out to the right. Leave the park and take the alley in front of you back out to Shinobazu-dori. Notice how the old houses in the alley open right out into the alley and how every niche has a bicycle or a motorcycle jammed into it.

Turn left on Shinobazu-dori and cross it at the next traffic signal, 20 meters away. Five years ago. none of these tall, totally undistinguished buildings you see along Shinobazu-dori was here. Residents feel their way of life threatened.

Go down the street going off from Shinobazu-dori at the traffic signal, leaving the bunking gray presence of the NTT Building on your right. At the end of this short street, turn left onto “Yomise Dori,” so written in kana over the Buck-Rogers style arch spanning this street of typical old downtown shops.

There’s a rice merchant (a 40-kilo bag for ¥5,600—so expensive because the rice farmers are heavily subsidized and the outlets strictly controlled), a shop selling all manner footgear from plastic sandals to wooden geta, a tofu maker, a sake shop, and

2. Ikeda-ten, the kamaboko (fish cake) maker, under a green awning. A quick Tokyo snack here, maybe? Ask for “ba-ru” and you will get for ¥100 six “balls” of deep-fried squid tentacles and chopped onion on a bamboo stick, perfect for munching on while walking, a little pleasure not yet fully sanctioned by Japanese etiquette but which here in shitamachi is perfectly OK.

Stroll on by the vegetable store with everything laid out with crisp precision and the konyaku maker with his great wooden and plastic mixing tubs. (Kenkyusha’s Japanese-English Dictionary identifies konyaku as “a paste made from the starch of devil’s tongue,” which only serves to underline the essentiality of experience over mere description.)

Even at the risk of the shopkeeper s not being able to move around in his tiny shop, everything is laid out for the customer to see and before any purchase can be made, it is necessary to pass the time of day. There is a bond here between merchant and customer which may well go back generations on each side.

On your right at the corner you’ll come to a shop called Kyoto which sells bento lunch boxes. Next to it is a rather self-conscious archway labeled “Yanaka Ginza” in kana. Turn right through this arch onto a tiled road, very fancy, as befits the neighborhood’s main shop-pine street.

Along Yanaka Ginza you will also find a wondrous profusion of shops, most with their goods for sale and their carefully tended pots of flowers and greenery spilling out into the street: a florist; a MOS Burger fast-food hamburger shop playing Mozart to set a mood; a barbershop, whose customers are being submitted to an almost clinical concern (a “Little Adventure” for another day is a visit to a Japanese barber); a large fish store with an amazing variety of sea creatures laid out on ice, illuminated at dusk by lights as if jewelry—walk in: the family who runs the store has their quarters in the back. Then on the same side of the street you will come to the wonderful shop

3. Kamekichi Tea Merchant

Go in, all the way to the back, to the finely tooled brass mural of cranes which decorates the doors of the shop’s refrigerated store room. In the back of the shop there is a lovely garden off to the left, a little secret that everyone in the neighborhood knows about and now you, too. Everyone also knows that every visitor is without fail offered a cup of tea; you too, and you can sip it while inspecting the tea implements for sale and the many different kinds of tea shipped to the shop in tea chests from Shizuoka, Saitama and Kyushu.

The most expensive tea is Tenshin, 100 grams for ¥3,000, but ordinary ocha for daily drinks (Japanese when they first go abroad say the first thing they miss is ocha) is ¥300 for 100 grams. If the weatherfine the shop might put out in the street its battered old roasting machine which, as it turns the tea leaves over, produces a lovely scent, that most subtle advertisement imaginable.

On the left just at the end of Yanaka Ginza, past the hardware store, the chicken-parts store, the gardening-supplies store, the stationery store and the kimono store which has found out that in order to survive it must also sell fur coats, just as the tiles give way to ordinary paving, you will find

4. Goto no ame (“Goto’s Candies”), an old-fashioned sweet shop which, as you can surmise from the sound of the ancient machinery grinding away out back, makes its own. Myself, I am partial to the delicately sweetened hard candies called Tankiri at ¥200 a packet, while a lady I know prefers the Shoga Ame (same

price) which is made of ginger.

There are 20 other kinds, all unique to this shop. Taro-chan, the house mynah bird, is apt to blur out a quick “konnichi wa,” at some point during the proceedings.

At this point you might want to consider a quick detour. Running off the end of Yanaka Ginza to the left is a street 50 meters down which you will come across

5. Buseki Flower Basket Shop

Here the friendly Mr. Buseki, who dresses in comfortable Edo-style homewear, and his son, who favors Ralph Lauren sweatshirts, make the most exquisite baskets and vases out of well-smoked bamboo 100 year old, which they have procurer from under the thatched roofs of old country cottages.

You will be most graciously received, probably offered tea and invited to inspect some of the shop’s work, like the beautiful vase just put on reserve by the Portuguese Ambassador or the little tray of woven bamboo for ¥500, which just might suit you—who knows?