A New Discovery

One of my weaknesses is auction and exhibit catalogues. Aside from being a regular subscriber to Sotheby’s, I also receive a dozen or so art magazines which inform me of exhibits, sales and auctions taking place around the globe. This keeps me abreast of what’s happening in the art world and up-to-date on the pricing, also important as I’m constantly buying pictures.

One of the other great benefits from this pursuit is the discovery of another artist who had been unknown to me. There are hundreds of artists whose names appear quickly in large composite exhibitions as examples of a particular period, style or technique but, as they are usually represented by a single picture among many, it becomes easy to forget them.

I recently received a catalogue from Germany from the C.G. Boerner Galleries in Dusseldorf. (They also have a branch in New York City.) The entire catalogue was devoted to the etchings of only one artist — “Cornelis Bega” who was born in either 1631 or 32 and died in 1664. A short life of only 32 years. The pictures looked a little familiar and, after searching, I found the same prints offered for sale in a Sotheby’s Catalogue about eight years ago.

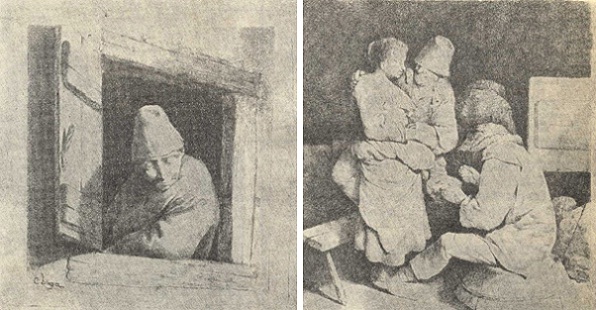

Neither the Sotheby’s Catalogue or the one from C.G. Boerner offered any information about the artist. My curiosity was aroused for two reasons. First, it seemed unusual to offer a catalogue on just one minor, almost unknown, artist and, second, his subject matter was almost entirely devoted to lecherous old men trying to seduce young girls. An interesting fellow, indeed, and one worth researching.

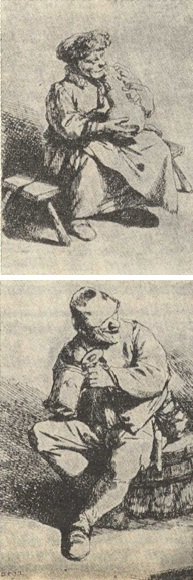

It’s fun owning an art library and when it comes to researching a fellow like Mr. Bega, it really pays off. I discovered him in four of my books. The index to the “Master Drawings Quarterly” showed him listed in a 1974 issue on Dutch drawings in a collection which was donated to the Metropolitan Museum in New York. Here the author states that Bega was still insufficiently defined as “a graphic artist,” but in this drawing of a seated woman shows himself as a sensitive and most competent draughtsman.

A catalogue from the Frits Lugt Institute in Paris of Dutch 17th-century drawings not only illustrates a beautiful full-figure study of a young girl, but also gives a short biography of our young unknown artist.

He was born and died in Haarlem, the son of a gold and silversmith and grandson on his mother’s side of an artist. His teacher was the famous Adrian Ran Ostade. Aside from one year spent on a sketching to Germany with a group artists, he spent his entire life in Haarlem. The interesting fact that turned up in reading and looking at Bega’s work, is that the girl in the picture is almost always the same model.

She recurs again and again in Bega’s prints and probably was a member of his household. She must have been an interesting gal not only to have posed for his figure studies, but also as the victim for his assorted collection of heavy-hooded characters. I also thought that if she was so busy posing for Cornelis, when did she have time to clean the house?

There is no question that Bega knew how to draw. The figures are solid and, within that narrow distance of a stage allotted to them, beautifully related to each other.

The classic book “Art of Etching” by Lumsden illustrates one of the same etchings as in the German catalogue, but this 1924 book lists “The Doctor” for the same picture the Boerner catalogue shows as “Le Cabaret.” The Sotheby’s Catalogue title for this picture is ‘The Young Hostess.” Life styles have changed in 64 years so that we can read a completely different meaning into what is very obvious.

In “The Print Collectors Handbook” written by Alfred Whitman of the British Museum, published in 1902, Bega is dismissed in one short paragraph, which I quote: “Ostadel pupils include Cornelis Dusart and Cornelis Bega who, though they followed in the footsteps of their master, fell far short of the excellence he attained.”

Obviously, Mr. Whitman had no imagination, not to mention a sense of humor. Bega’s pictures are not only descriptive of an age long past; they also are specimens of good drawing and fine printmaking.

From nowhere Mr. Bega has all of a sudden become a welcome addition to my world of art.