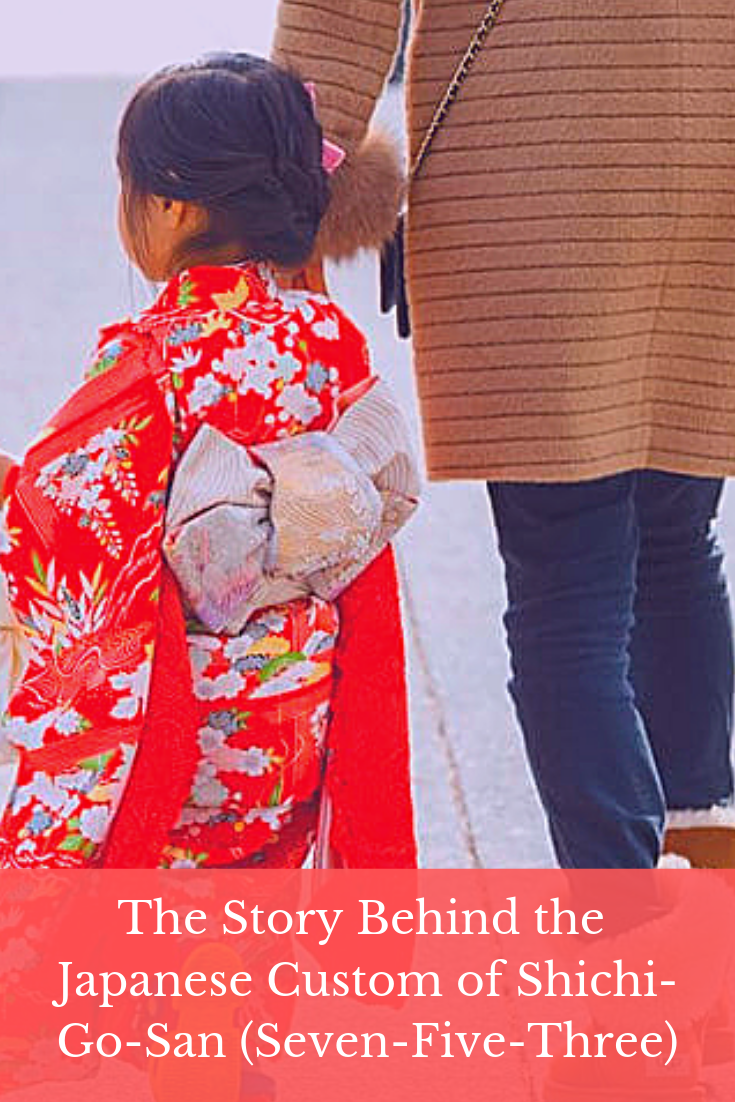

Come November, shrines across Japan will be busy with floods of children of a certain age, decked out in kimono for girls, and hakama for boys. Often the whole family — granny and gramps included — will attend, and it’s a day for everyone to dress up and go out for a meal.

What’s the Significance?

Shichi-go-san literally means seven-five-three and represents the ages of the kids being celebrated as they reach certain milestones. In modern days we tend to focus on physical milestones, for example: at three, children’s language development increases significantly; at five there’s a clear development of logical thinking; at seven many kids usually start (or have already begun) losing their baby teeth. But back in the day, milestones were based on predominantly cultural signifiers.

It’s because of this that boys and girls are celebrated at different ages:

Three Years Old (Boys & Girls)

Girls and boys’ hair was allowed to grow out. Until then, children’s hair would have been kept short. This event is called kamioki (髪置き), which means “to leave the hair” and let it grow out. (Traditionally, both boys and girls can have their first celebration at age three, but these days it’s more common for girls to go twice and boys only once.)

Five Years Old (Boys)

Back when kimono was the norm, this would be the age that boys would start wearing hakama, signifying their start into adulthood. Boys from samurai families would also start wearing haori (kimono jackets) with the family crest on it. This is called hakamagi (袴着), and literally, means “to wear hakama.”

Seven Years Old (Girls)

Girls began wearing something close to a proper traditional kimono with an obi tie. Until then, they would have worn a cord around their waists or simply had strings attached to the kimono to keep it tied together. This is called obitoki (帯解き), meaning “to figure out the obi” and indicates girls’ transitioning into womanhood.

As children grow, they encounter so many changes and risk of illnesses, so at these ages it was a time for parents and families to thank the gods for letting their children overcome these. These days, it’s more of a coming of age celebration for families to show affection for each other and allow their kids to have a special day. They visit the shrine, pay a gratuity fee and plod home again. Many will take professional photos to commemorate the event.

Where Does the Custom Come From?

Though there seems to be some debate as to when the custom first appeared, it’s believed it first started in the Heian period (794-1185) but was exclusively for members of the Imperial Family and surrounding nobility.

Others date the origins of the ceremony back to the Muromachi period (1336-1573). Back then, infant mortality was high and many people waited until their kids were three to four years of age to add them to the family registry. The ceremony showed gratitude for the child living this long and gave the family an opportunity to pray for future good health and long life.

By the Edo period (1603-1868) it spread through samurai society from the Kanto region to the rest of Japan for commoners. Once the Meiji Period (1868–1912) hit, Shichi-go-san took on a style similar to what we see today (minus some modern modifications, of course).

Why Is It on November 15th?

Technically, families can visit a shrine for Shichi-go-san any time in November, but the main date is November 15. It’s common for families to go on other days partly because of scheduling issues, and most shrines will start accepting visitors from mid-October, and some even begin in September.

When the practice started in the Heian period, it was a different date — November 15 became the custom from the Edo period. This day was chosen because dog-lover Shogun Tsunayoshi Tokugawa (often nicknamed Oinusama or the dog shogun for his love of the animal) wanted to celebrate his son Tokumatsu on that day, and eventually others followed suit.

There are a number of reasons why he chose this day, and why it has remained the standard date to celebrate Shichi-go-san. It falls on a day called kishukunichi (鬼宿日), which literally means “the day the demons stay at home.” It’s supposedly a fortuitous day for celebrations that aren’t weddings.

Also, according to the traditional lunar calendar, November was the month in autumn to thank the gods for the year’s harvest. The 15th of the month would be a full moon, and so people thanked the gods for letting their kids “ripen with age” as well.

An added bonus, 15 is the sum of seven, five, and three — a perfect representation of the ages celebrated, and they are also all odd numbers, which are considered more auspicious in general.

Tsunayoshi Tokugawa

What’s with the Sweets?

The custom of giving candy started in the Edo period. The long sticks of stretched sweet candy called chitose ame (千歳飴) represented a wish for long life. The sweets come in red and white, notoriously auspicious colors used for celebrations. The children will be given the number of sweets to match their age — three sticks of candy for a three-year-old, and so on. The candy sticks are put inside a plastic bag and usually given to the child by the parents, grandparents or neighbors.

Often, the words written on the bags containing the sweets will be either kotobuki (寿, meaning both congratulations and long life), shochikubai (松竹梅 – pine, bamboo, plum: grouped together they have an auspicious meaning) or tsuru wa sennen, kame wa mannen ( 鶴は千年、亀は万年: a crane lives for 1,000 years, a turtle lives for 10,000 years), all auspicious words and phrases wishing for longevity and good health.

But these days, kids aren’t the only ones getting treats. It has become more common for mothers to exchange gifts as well, as a thank you for watching over their children.

Where to See the Event

Most neighborhood shrines will have flags up during November indicating that families can come by for the ceremony, which can either consist of a simple visit to the shrine and some photo taking, or, in increasingly fewer cases, a short ritual performed by a Shinto priest.

Traditionally most people would go to their local shrine, as this shrine would have been directly involved in the families’ daily lives. Nowadays though, people choose shrines based on convenience, general atmosphere, and whether their friends will go to the same one. Some mamatomo groups will attend a Shichi-go-san event together followed by a party at someone’s house, making it a fun event that the kids can celebrate with their friends.

Some shrines will accept Shichi-go-san reservations from September onwards, but October and November are the most popular months. Naturally, the busiest time will be around mid-November — especially on a weekend. So why not stop by and get a taste of the tradition.

Note: It is generally taboo to take pictures of children in Japan without permission; even more so to upload their photos online. Please be sensitive to parents’ and individuals’ concerns for privacy.

All images except for that of Tsunayoshi Tokugawa: Shutterstock (with signed model release)

Tsunayoshi Tokugawa image: Public Domain

Learn how to wear kimono and get photographed in Ginza!

Try a casual kimono dressing lesson in Tokyo

Experience Exquisite Japanese Culture: Kimono, Tea, Dance!

Premium Kimono Rental in Kyoto: Furisode, Montsuki Hakama!