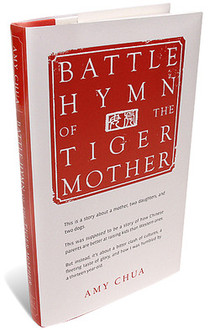

The Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother

by Brian Christian

Does the name Sophie Chua-Rubenfield ring any bells? Her father is Robert R. Slaughter, Professor of Law at Yale and the best-selling author of two smash-hit mystery thrillers, but it is to her mother that Sophie owes any real claim to fame. Amy Chua is the eponymous Tiger Mother of the provocative Battle Hymn essay (Why Chinese Mothers are Superior) that caused such a stir a couple of years ago. Do you remember it? This was its opening manifesto:

Here are some things my daughters, Sophie and Louisa, were never allowed to do: attend a sleepover; have a playdate; be in a school play; complain about not being in a school play; watch TV or play computer games; choose their own extracurricular activities; get any grade less than an A; not be the No 1 student in every subject except gym and drama; play any instrument other than the piano or violin; not play the piano or violin.

The essay and subsequent book certainly aroused some strong feelings. I remember there being particular outrage about an anecdote recalling her birthday when she threw her daughters’ hand-made cards back at them because they simply weren’t good enough.

Mothers of a more liberally-minded persuasion raised their hands in horror when they read that she threatened to burn all of Sophie’s stuffed animals after one less than perfect piano practice, but it was the “Little White Donkey” episode that drove many readers over the edge. That’s the name of the violin tune that Sophie’s 7-year-old sister Lulu was made to repeat for hours on end — right through dinner into the night, with no breaks for water or even the bathroom, until at last she mastered the piece.

For an educator of more than 30 years’ experience and the father of three fairly laid-back boys who, I have to admit, were brought up in a very different regime, The Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother made fascinating reading.

I was Principal of an academically selective school in Singapore at the time of its publication, one of just three schools licensed to educate both Singaporeans and international students; this afforded me a privileged vantage point from which to observe the reactions of very different types of parent.

Interestingly, it tended to be the Asian mothers (and fathers) who picked up on the very significant elements of self-parody in the book, while our western parents seemed to take it at face-value and saw Ms Chua as some sort of “monster mom” practising child abuse of the cruellest kind. I wondered how so many of them could fail to see that the self-styled Tiger Mother was, at least to some extent, poking fun at herself – even when she expressed disappointment at the lack of ambition shown by the family dog or admitted defeat in her attempts to interest her daughters’ pet rabbits in a programme of self-improvement.

I suspect that it had something to do with those two dark spectres familiar to any parent: guilt and self-doubt. Am I spending enough time with them? Am I doing the right thing? How come everyone else makes it look so easy? I suspect too that there was a sense that there might just be a glimmer of truth in Amy Chua’s assertion that we can ask more of our children than we typically do and that true self-esteem has to be earned.

Today, as Principal of the British School in Tokyo, working with children of almost 60 different nationalities, I believe that we should assume strength rather than weakness in our children and that we are right to have high expectations of them.

Young people never cease to amaze me with their capacity to respond to a challenge, and I feel certain that the greatest disservice we can do them is to expect less than they are capable of delivering. It’s not about top grades or gold medals, but – as the Tiger Mother herself explains – it is about believing in your child more than anyone else.

Sophie Chua-Rubenfield appears to be a pretty good advertisement for her mother’s parenting approach. The fact that she made her debut as a concert pianist in Carnegie Hall at the age of 14 and is now in her second year at Harvard may have more to do with her genes than her upbringing but, for such a prodigy, she seems to have grown up into a surprisingly grounded, normal young woman (who blogs, here). Let me leave her with the final words:

What does it mean to live life to the fullest? Maybe striving to win a Nobel Prize or going skydiving are just two sides of the same coin. It’s all about knowing that you’ve pushed yourself to the limits of your own potential. You feel it when you’re sprinting, and when the piano piece you’ve been practising for hours finally comes to life beneath your fingertips.

You feel it when you encounter a life-changing idea, and when you do something on your own that you never thought you could. If I died tomorrow, I would die knowing that I’ve lived my whole life at 110%.

Brian Christian is the Principal of the British School in Tokyo. He blogs at the BST website: www.bst.ac.jp/principalsblog

Image: sebra / Shutterstock.com