This March, after years of international pressure, Japan took steps towards joining Hague Convention on the Civil Aspects of International Child Abduction, also known as Hague Abduction Convention. The convention, drafted in 1980, lays out a legal framework to deal with cases in which children are abducted internationally by one parent without the other’s consent or against custody agreements. There are currently 87 signatories.

Countries that have signed the Hague convention agree to return internationally abducted children to their countries of habitual residence as quickly as possible so that parents can work out custody arrangements through those nations’ family courts. Japan is the only Group of Seven nation not to have signed the Hague pact.

Of the G8 countries, only Japan and Russia have not signed the Hague convention. As the number of Japanese citizens living overseas has almost doubled in the last twenty years, parental abductions have also increased. The US State department estimates there are about 100 cases of children abducted to Japan in violation of custody arrangements reached in the US. There were, according to the US embassy, an additional 31 cases in which both parents and the child or children live in Japan, but visitation denied. The British embassy in Tokyo reports 38 cases since 2003.

Perhaps the most high-profile dispute involved American, though naturalized Japanese, Christopher Savoie (left, with his then-wife and children during happier times), who was arrested in Japan after his ex-wife accused him of abducting their two children.

Noriko Savoie had violated a custody decision made by a US court in Tennessee, keeping the children in Japan and enrolling them in local school after agreement for six week summer trip was reached in the divorce proceedings. The case was eventually dropped by Japanese prosecutors.

In 2011, in response to international pressure, then-Prime Minister Hatoyama announced plans to submit legislation to the Diet to join the convention. The bill was submitted in March of this year but has not yet passed. With just over five weeks left until the end of the current Diet session and the opposition Liberal Democratic Party is still voicing objections to the bill, its passage looks uncertain.

At the moment, since Japan is not yet a member of the Hague convention, foreign parents whose Japanese partners have taken their children back to Japan without their consent or against custody agreements reached overseas must appeal to Japanese family courts to order the return of their child or children. However, rather than simply order the enforcement of pre-existing custody agreements reached in foreign courts, Japanese family courts consider each case anew and may decide to grant one parent sole custody.

Since Japanese family law does not recognize joint custody, if the court grants custody to the Japanese parent, the foreign parent must work out visitation arrangements with their Japanese ex-partner. If the Japanese partner doesn’t want their children to maintain ties with their foreign parent, the foreign parent has, at the moment, very little legal recourse.

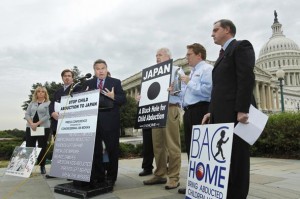

If Japan joins the Hague convention, responding to international pressure (pictured right is a conference in the US with relatives of abducted children) that could change. If Japan signs, family courts here would be limited to deciding whether internationally abducted children under the age of 16 should be returned to their countries of habitual residence under the terms of the convention.

Japanese courts would still have the final say and could decide not to order a child’s return in some cases. If a Japanese parent can prove abuse at the hands of their foreign ex-partner overseas, for example, Japanese family courts may decide that ordering the abducted child’s return is not in the child’s best interest. Also, if more than a year has passed since the alleged abduction, courts may decide that a child has become accustomed to his or her new life in Japan and decide not to order the child’s return. Despite these provisions, some lawmakers still claim that the bill does not go far enough to protect Japanese women fleeing domestic violence in their international marriages.

Even if Japan does pass the proposed legislation and join the Hague convention, the convention is not retroactive, so it would not apply to cases of alleged parental abduction to Japan that have already occurred. Nonetheless, Japan’s tentative steps towards joining the convention offer new hope for parents of children from failed international marriages.

By Annamarie Sasagawa