Tamsin Bradshaw gets the lowdown on the AIDS issue in Japan and how we can help

AIDS is a global phenomenon, and one that Japan has yet to face up to—at least when it comes to awareness and education. According to the 2006 report prepared by the Joint United Nations Program on AIDS (UNAIDS), approximately 38.6 million people worldwide were living with HIV by the end of 2005. Japan, however, is still experiencing a below capita infection rate. Around 13,500 people are living with HIV/AIDS nationwide.

While this number may seem small, it is steadily growing. And the experts suggested that up to 50,000 people could be infected nationwide by 2010. “The issue will grow if more is not done now,” says Louise Haynes, Director of Japan AIDS Prevention Awareness Network (JAPANetwork), which promotes AIDS education in the EFL/ESL classroom. Alarmingly, while infection rates are rising, local understanding of this virus is not.

The Basics

HIV—human immunodeficiency virus—is the virus which causes AIDS. HIV is transmitted through unprotected sexual intercourse with someone who has HIV, unprotected oral sex (although this is a far rarer means of transmission than sexual intercourse), needle sharing, or mother-to-infant transmission during pregnancy, childbirth, or breast-feeding.

In Japan, the most common source of transmission prior to 2000 was contaminated blood products. More recently, unprotected sexual intercourse has overtaken as the main means of transmission, with 25.6 percent of HIV cases due to heterosexual intercourse, and 60 percent due to homosexual intercourse.

No matter what the means of infection, the outcome is the same. HIV weakens the immune system, until it eventually breaks down. At this point, AIDS, or acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, kicks in, exposing its victim to illnesses they would not otherwise be so susceptible to; such as the common cold, pneumonia, or cancer.

Why AIDS is a Problem in Japan and What We Can do About it

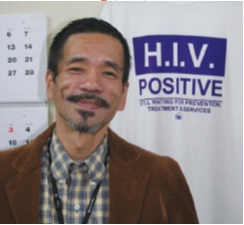

One of the big issues in conservative Japan is that illnesses are seen as shameful. “The Japanese AIDS community is fighting against stigma,” says Hiroshi Hasegawa an AIDS activist who runs Japan Network of People Living with HIV/AIDS (JANP +). According to Hasegawa, who was diagnosed as HIV positive in 1992, three out of ten people who are newly diagnosed already have fullblown AIDS symptoms. They should have been tested years ago, but most people are so afraid of being outcast from their jobs and their circle of friends that they avoid getting tested at all. At the very least their fears drive them to hide their HIV positive status.

Some local doctors do not help matters either, says Hasegawa. “They understand only the defensive side of AIDS” and see people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) as infective rather than just infected, he says.

Another obstacle on the road to AIDS awareness is the Japanese view of sex as being an inappropriate subject for discussion, says Hasegawa. This leads to misconceptions about how the disease is spread, says Haynes. She says that most university students “are unable to clearly state which behaviors could pass the virus from someone who has the virus to someone who does not.”

Masako Kihara, assistant professor at Kyoto University Graduate School of Medicine and prominent international AIDS researcher has a similar perspective. Kihara says that while most high school students know what AIDS is and that it’s becoming increasingly prevalent, the majority of them think that “our place is safe.” This “it could not happen to me” attitude is widespread, and the World Health Organization’s report that as few as 6–25 percent of young adults in Japan use condoms only supports this.

Both Haynes and Kihara see improving education as the way forward. Kihara has started WISH education (Well-being of youth In Social Happiness) to personalize risk. She also uses WISH to provide students with educational materials that she hopes will help them make sensible lifestyle choices. “I [don’t] prohibit anything …I’d like them to think about human relationships.”

Haynes promotes government involvement in protecting the public. “[The government] could require that all high school students (and some would argue junior high as well) receive comprehensive AIDS education, including knowledge of condom use and other barriers to HIV and STD infection.”

While local awareness has a

long way to go, Japan is well

ahead of the curve when it

comes to treatments.

According to Haynes, education encourages students to take matters into their own hands. “I have had several students come up to me or write that they have talked with their partners about using condoms,” she says.

Raising awareness is clearly one way to change local attitudes to AIDS, and, “the motivation is strong,” says Hasegawa. Not only will education help prevent infection, it will also persuade those who desperately need the treatments to come forward. While local awareness has a long way to go, Japan is well ahead of the curve when it comes to access to life-prolonging anti-retroviral treatments (ARVs). “Japan’s situation is very unique,” says Hasegawa. The cost of treatment is surprisingly cheap, thanks to national health insurance and the lobbying efforts of HIV positive hemophiliacs ten years ago. Low income groups will pay as little as ¥5,000 a month, with the highest income brackets parting with only ¥20,000 a month. In the developing world, AIDS is a matter of life or death, but in Japan, “AIDS is something we can live with,” says Hasegawa.

That’s not to say we should get complacent. Hasegawa argues that we need to find the right balance: not take things too seriously but not make light of AIDS, either. He also says it’s important to understand how PLWHA feel. They are the ones who really understand what’s necessary—in terms of prevention, testing and medical treatment—in the fight against AIDS.

Haynes suggests that if the Japanese media got involved in educating the public, it would make a big difference. And “posters could be placed in subways and on buses to remind people to get tested and offer telephone numbers of AIDS hotlines or other support organizations,” she says. “Parents could sit down with their children and…provide them with pamphlets or other forms of information.” Both Haynes and Hasegawa also think it’s important that businesses acknowledge HIV/AIDS and learn how to deal with workplace discrimination which is based on a health condition.

As for how you can help, World AIDS Day is a way to get involved with fundraising and awareness. World AIDS Day is hosted every year on Dec. 1. JAPANetwork holds an annual AIDS candlelight memorial in Nagoya from 6pm. To find out what else you can do, check out www.worldaidsday.org.

Who You Gonna Call?

When Hasegawa was diagnosed as HIV positive, he lost contact with many friends, gave up work and says he almost gave up living. He sorted himself out, but without the emotional support he needed and which was lacking at the time in Japan. These days, if you’re looking for someone to talk to, want advice or just want to know more about AIDS, help is much closer at hand than it was in the early 1990s. Various organizations around the nation offer counseling and advice to both Japanese and English speakers.

Groups such as Japan Foundation for AIDS Prevention (see ‘How to Get Tested’), Hasegawa’s JANP+ (03-5367-8558, www.janpplus.jp), and Gay Friends for AIDS (03-5386-1575) can offer you all the moral support you need, so there is no need to feel alone. The gay community in particular has a rich support network.

Community Center akta and Community Space Dista provide a meeting place where people can get information on HIV/AIDS in Tokyo and Osaka respectively. Japan has access to the right drugs and has the beginnings of the right support networks to fight AIDS effectively. And, as Hasegawa says, the Japanese have a culture of being helpful to one another—it’s just a matter of translating this to the AIDS problem by fostering education and understanding. Hasegawa’s smiling face is living proof that there’s hope yet.

How to Get Tested

Getting tested for HIV is as simple as a blood test. Most medical clinics can perform this test easily, and the results are completely confidential. You should receive your test results within the week. Most testing facilities do not have English-speaking staff, so it’s advisable to take someone with you who can speak Japanese. HIV/AIDS specialist facilities are also available. These include the Japan Foundation for AIDS Prevention, whose eight-language hotline (Tel. 03-5940-0212; www.jfap.or.jp) offers round-the-clock assistance on testing and counseling. The Japan HIV Center (Tel. 03-5259-0256) provides English-language testing advice every Saturday between 12–3pm.

How to Protect Yourself

There are two must-follow rules for protecting yourself against AIDS. One, don’t share needles and two, don’t have unprotected sex (intercourse or oral sex). Condoms are on offer in convenience stores and at Condomania (visit www.condomania.co.jp for locations) so there is no excuse for not having safe sex. If you do choose to have unprotected sex with a partner, be sure that you both get tested first. Expectant mothers—particularly those who believe they may have been exposed to HIV at some point—should also get tested. Timely treatment can prevent HIV being passed on to an unborn child.