Jim Dougherty considers the implications of Japan’s international military expansion

In 2002, the Japanese government decided to dispatch its high-tech Aegis warship to the Indian Ocean as a symbol of support for U.S. action in Afghanistan. It was a first, big step, in Japan’s expanding military activities around the world.

The Aegis — a state of the art destroyer with an air-defence system that can track objects hundreds of kilometers away as well simultaneously launching attacks on up to ten targets — is being used to collect data then shared with U.S. forces. Pre Sept. 11, an Aegis dispatch — in cooperation with another country — would have been unthinkable.

Now, having sent non-combat troops to Iraq, Japan has entered a new era. Many Japanese feel a strong obligation to join the international war on terror, not least due to North Korea’s obvious interest in nuclear options and China’s military build up over the last decade. However, few Japanese citizens are aware that their country already has three conventional destroyers deployed in the Indian Ocean to protect refueling ships. These destroyers are also sharing intelligence with U.S. forces.

In August 2003, Tokyo announced its intention to deploy an advanced two-phase layered missile shield based on U.S. technology. These plans represent a radical shift in Japan’s missile defense policy. The initiative is intended to confront expanding nuclear threats from North Korea and China. It’s not exactly a new issue — Japan’s cooperation with missile defense issues stretches back to the early 1980s with Ronald Reagan’s Strategic Defense Initiative. However Japan now seems willing to address important command-and-control issues, as well as re-examine the legal and constitutional issues associated with its ban of collective security activities.

Most surprising, perhaps, is that Japan’s armed forces have quietly expanded and now enjoy the third largest military budget in the world. Known as the Self-Defense Force, it has a current budget of ¥4.9 trillion ($46.7 billion).

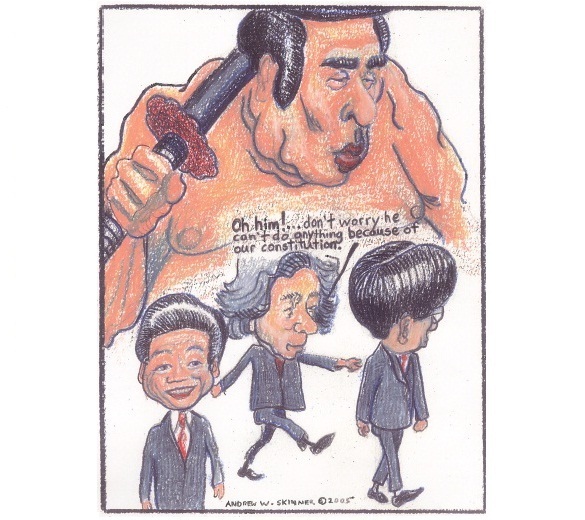

A majority of Japanese lawmakers now support transforming Japan’s constitution, which would give the military an expanded role in world peacekeeping efforts. UN peacekeeping missions in Cambodia in 1992 and similar activities in East Timor may have changed public perceptions. Japanese soldiers stationed in southern Iraq are limited to humanitarian relief and reconstruction; however, it’s a distinction that is lost on most Iraqis, many of whom see the troops as partners in the U.S. led military occupation of their country.

From a political point of view, Tokyo needs to maintain close military ties with Washington to offset the growing nuclear threats from North Korea and China. Japan’s expanding role and desire to increase military cooperation is winning praise in Washington. This acceleration in Japan’s security policy is creating new opportunities for the two countries to work together, modernize their alliance, upgrade their capabilities, and strengthen their ability to deal with the new challenges of terrorism.

Stability in East Asia depends heavily on the relationship between China and Japan. However, a negative trend in the relationship has prompted rivalry for leadership in the region. The upsurge in China’s power and influence in Asian affairs and its military assertiveness towards Taiwan coincide with a long period of economic recession in Japan. Many Japanese view China’s military size and phenomenal economic growth as undercutting their country’s leading economic and political role in Asia. Other Asian nations worry that Japan, with an expanding and more powerful military, could repeat the horrors of the 1930s and ’40s.

The Liberal Democrat Party is seriously considering an overhaul of the post-war constitution to allow the military to use even more force during international missions. They plan to announce a final draft of this new policy as early as November 2005. It would mark the first revision of the constitution since 1947. Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi has said that the constitution should be revised “in the light of common sense.” A constitutional revision would require a two-thirds majority vote in both houses of the Diet. A recent Yomiuri Shimbun poll showed 65 percent of citizens favor some constitutional change, with most saying the current document limits Japan’s role abroad. Whether Japan’s neighbours agree remains to be seen.