Henry Scott Stokes is moved by images that take you beyond what the eye can see

IT’S TERRIBLE being poor. You can’t move. But just imagine being blind. Most people who are blind are poor. There is not much work they can do. Life is hard. But still there are chances for a blind person. He or she can live an almost normal life, with a bit of luck. You are not condemned to being “handicapped” if you know better.

I became aware of this through a friend called Hideaki (“Tony”) Kase. Like me, he is a journalist. Unlike me, he has devoted himself to the cause of the blind. He has done so for more than 20 years. For a long time, I was totally unaware of this. This is another way of saying the obvious. He didn’t tell me about his voluntary work.

Even now, he’s shy about it. Not long ago I received an official invitation from him. I put it on top of a bundle of papers on my desk, to be attended to. And before long other envelopes arrived, and they went on top, and gradually that invitation got submerged. I knew it was there but I didn’t do anything.

One day Tony asked me: had I received his invitation to an exhibition of photos by the blind? Here was the chairman of the organizing body gently prodding me for an answer.

Ouch!

Faithless friend that I am, I promised to show up — for the second year running. Last year, I failed to keep my promise, this time I had to. It was time to pull myself together.

All this is a long-winded way of saying…You may be rich, and you may be sighted — you may have all the blessings of this world. But still you can enjoy seeing how the world looks to those who cannot see their own photographs. I finally went to that exhibition of photos taken by the blind, organized by Tony. He put it on in Shinjuku for five days at the end of last year.

Prince Tomohito, a member of the imperial family, opened the exhibition. He toured the show, starting with a photo that featured as the prize-winner in the exhibition. This picture looked, at first glance, like nothing more than an array of blue thistles. At first, I confess, I didn’t get the point. I had to look at the photo several times, to spot the point of the picture — a dragonfly had cheekily posed himself on the thistle right in the middle.

This you should know. If someone goes blind, that person’s other senses develop to a phenomenal degree. That blind photographer could hear the wings of the dragonfly beating.

I am reminded of Zatoichi, the fabled blind swordsman — as played by Beat Takeshi in a recent movie. All of a sudden he whips out his trusty blade and dices his enemies.

How did he know they were there, someone asks?

“I smelled them,” says Zatoichi.

The other day I and a friend — he is Per Bodner, a professional photographer from Sweden — spent a couple of hours rummaging in a storage in Nihombashi, to see what treasures the blind photographers had furnished for exhibitions over the last ten years. Helping us was Fumiya Shinozaki, who runs the economical office of the group that Tony heads in his free time — the Nippon Bunka Kyokai.

Our idea was to follow their example and to get enough pictures to put on an exhibition — albeit a small one — of photos taken by the blind. The show is due to open at the Foreign Correspondents’ Club of Japan on Monday, Jan. 31. I salute Per, the chairman of our exhibitions committee — he made the selections.

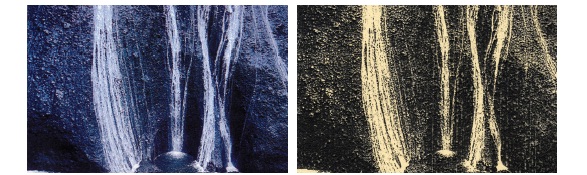

However, how do blind people take photos, you may still ask? Tony explained this to me. According to him those automatic cameras that we all have these days came into general use a generation ago, and they enable a blind person to focus a camera. The rest is instinct. But how do the blind see their own pictures? How is it possible? The key was the development here of a process to turn photos into 3-D plates. A blind person touches such a panel, to know what’s in a photo.

“This way the blind can touch scenery. r moving things,” says Tony, “without the 3-D panels they have no idea what is there in their own photos — they are crucial.”

Each photo in the FCCJ exhibition comes with a 3-D panel, to make this point.