Jazz violinist comes to Tokyo

by Anthony George

Music, said the French philosopher Michel Leiris, is the art form that touches the senses most directly, possessing the mysterious power to move one into states of rapture and delight. It enables us somehow to feel life more deeply, to come closer to ourselves.

Anyone who’s heard jazz violinist Billy Bang in a live performance will certainly have experienced the transporting powers of music. One of only a few significant violinists in jazz, Billy Bang (the name is a school-days moniker that stuck, although it now seems an appropriate reference to his explosive stage performances) has created important innovations of style and technique that have influenced a generation of string players.

For more than 30 years, he has created music that is characteristically engaging and visceral — music that pulls at the senses and demands your response.

About his playing he says, “I try to communicate with people. I try to tell them stories and offer them images through the music. I always try to share the moment with others, and hopefully the thoughts are always about peace and reconciliation and love.”

The will to inspire peace is something very central to Billy’s aims. “Through music, people from different backgrounds and languages and different histories seem to gel, to come together in a very peaceful co-existence.

“Sometimes, after I perform, people from the audience will come to me extremely satisfied as though they have been taken on a journey and seen things they don’t normally see every day, and they are very pleased. That gives me satisfaction.”

The story of how Billy came to music is itself a poignant journey. Like so many young men of his generation, right after high school, Billy was drafted into the army — a short trip from the concrete streets of Harlem to the devastating jungles of Vietnam. Inevitably, what he experienced there changed his life.

When he returned, it was to a different world. “I didn’t think I could cope, and I didn’t feel as if I fit anymore…I didn’t talk much about it, except to close people who knew me. And, although I am a gregarious person and like to speak, I was withdrawn and maybe just scared in not knowing how to deal with life.”

Billy’s experience of war, however, drew him to music, despite the promising prospect of a career in law and its accompanying financial rewards. “As a pre-law student and a paralegal, I witnessed all the under-the-table, underhand things that happened in the justice system. . .I felt bad enough because I thought what I did in Vietnam was wrong, and I didn’t want to join forces with anything else that represented that same unfairness,” he says.

“I felt the only way I could atone myself for what I did in Vietnam was to approach life from a more peaceful way, a more spiritual way. The closest thing for me in that area was music.”

Billy had studied classical violin during two years at an experimental high school in Harlem but now had to re-learn the instrument. It was in this process, and in trying to find a voice in New York’s bourgeoning progressive-jazz scene of the time, that he developed his innovative and influential approach to the instrument.

Inspired by saxophonists such as John Coltrane and Eric Dolphy, he found ways to emulate saxophone phrasing (governed by a reed player’s need to draw breath) on the violin.

Billy went on to play with legends such as Sun Ra and has recorded over twenty albums as a leader. As with most musicians who pursue a path of creative individuality rather than commercial success, financial reward is often elusive.

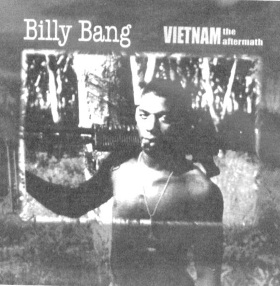

In 2003, Billy was awarded the Association For Independent Music Award for his album, Vietnam: The Aftermath. The idea of an album reflecting on his experiences in Vietnam was a project Billy had in mind for a long time but was hesitant to approach. In the liner notes, he writes, “My inability to bravely confront…my experiences in Vietnam has been a continuous struggle…At night, I would experience severe nightmares of death and destruction and, during the day, a kind of undefined, ambiguous daydream.”

Finally, at the suggestion of Justin Time Records boss Jean-Pierre Ledu, he agreed to embark on the project. Still, he says, “I didn’t really know on what I was embarking. I didn’t know how deep this event would take me, how the impact of it would be felt.

“Once I started, I began opening up much deeper thoughts and feelings I had been suppressing. When I started writing, it started coming out…like a waterfall. It kind of caught me by surprise.

“I was able to exorcise those demons that were in me all this time. It was not planned, but it helped me more than any one thing I can remember. I can honestly say I’ve recovered the innocence of my spirit and soul again.”

The wide acclaim the album received is an indication of its power and beauty. It spawned the idea, now underway, of a film documenting Billy’s return to Vietnam, during which he hopes to perform at places where he once fought, together with Vietnamese war veterans. “It will be a peace celebration like never before,” he says.

Billy recently finished writing the material for a sequel to Vietnam: The Aftermath, which will also feature New York-based Vietnamese musicians and is slated for release next year on Justin Time Records.

In April, he comes to Japan, giving audiences here the opportunity to hear his uplifting narratives in a language that needs no translation.

For more into on Billy Bang see: www.justin-time.com