I don’t suppose it comes as a surprise to anyone that the main ingredient in Japanese sake, otherwise known as rice wine, is in fact rice. And most of you have probably already surmised that when it comes to making good rice wine, not just any rice will do. Like their brethren in the wine industry, sake brewers are constantly fretting and fussing over the quality of the rice they select for their sake. Over the centuries this natural selection has resulted in myriad varieties of specialty sake rice suited to the specific growing conditions in every part of Japan, just as there are now many varieties of wine grapes ideally suited to the micro-climates throughout Europe and beyond.

What may surprise you, as it did me when I talked with Masumi’s brewers about rice last week, is that, unlike wine, where the grape itself plays the leading role in defining a wine’s flavor and in many cases gets star-billing in the very name of the wine (Pinot Noir, Cabernet Sauvignon, Chardonnay, ad infinitum), a sake’s individual character does not come from the solo performance of the rice itself, but from the interaction of a host of smaller players, including the rice, the water, the rice mold and the yeast, to name only the principals in a cast of thousands.

Brewers aren’t looking for rice with its own unique qualities, but for rice that is strong in a set of common qualities that they know will provide a solid foundation upon which to slowly build character throughout the brewing process.

What Brewers Look For in Rice

If you’ve ever ridden a train out into the countryside from the center of one of Japan’s major cities, then you know you don’t have to go far if all you’re looking for is rice. After just a few stations the tight, concrete circuit board of urban sprawl gives ground to rice patches here and there among the houses and convenience stores, then the patches become a patchwork, and finally you find yourself gazing out the train window at a nearly unbroken sea of green-going-yellow now as the harvest approaches.

But what appears to us as a sea of green and gold remains a patchwork for sake brewers. Most of the patches out there are standard table rice, good for eating and for mass-producing standard grade sake. Very few of those verdant squares are made up of proper sake rice, and fewer still have the full set of superior brewing qualities listed below.

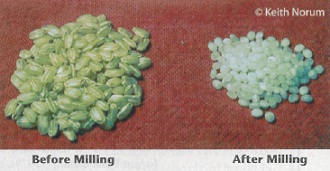

Large grains

Each grain of good sake rice is considerably larger than a grain of table rice. Brewers look for large grains because they have to mill the rice before they make sake, and milling grinds away as much as 60 percent of each grain. The larger the grain is to start with, the more you’ll have left to work with when the milling’s over.

Low-protein content

High protein in a cereal such as rice or wheat may be a very good thing when you find it in your rice bowl or an English muffin, but it’s not what you want to find in a glass of ginjo sake. Proteins, fats and other non-starch compounds complicate the sake’s taste in unsavory ways, so brewers select varieties with the least amount of these substances as they can.

Ample shinpaku

Shinpaku is the pure starch found at the core of the rice grain, and starch is really the only substance brewers want from the rice. The unwanted proteins and fats are in the layers surrounding the shinpaku core, so the whole point of milling is to grind away these outer layers to expose this core. Naturally, the bigger the core is, the less you’ll have to mill, and the more starch you’ll get from each grain.

Rice with good shinpaku also helps the koji rice mold to grow fully into the heart of each starchy core, and the koji mold is itself at the very heart of the sake brewing process.

Ease with which the rice breaks down during fermentation

Try as I might, I can’t come up with a shorter way to describe this quality. Meltiness? Too romantic. Solubility? Brings to mind white lab coats and beakers. Suffice it to say that brewers go out of their way to select rice varieties that dissolve easily and completely during fermentation.

Sake Rice Varieties: the best and all the rest

Japan is a long, mountainous archipelago with growing conditions that vary widely from north to south and from the coast to the central highlands, so the challenge for brewers over the centuries has been to find ideal rice that grows well in their area. This has resulted in hundreds of local favorites that brewers continue to use in their premium sake as a point of pride, even though modern shipping makes it possible to bring in superior rice from prime growing areas in other parts of the country.

There is one variety, however, that is so far superior to the other regional varieties that brewers throughout Japan import it in small amounts to use in their daiginjo (super-premium) sake.

This variety is called Yamada Nishiki. Cultivated in Hyogo, Fukuoka and Mie Prefectures, Yamada Nishiki is an extremely temperamental variety, sensitive to minute changes in soil moisture, amount of shade, growing season, ad nauseum, so even within the Yamada Nishiki variety the rice is graded and priced depending on exactly how much of the essential qualities it ended up with and on where it was grown.

Yamada Nishiki may be the gold standard of sake rice, but it has a price tag to match, so brewers rely on the best of their local varieties for most of their ginjo (premium) sake and a few special daiginjo (super premium) labels. There are more than 50 regional varieties in Japan, but here are the four best varieties that dominate the market.

Masumi’s brewers noted that new hybrids of these local varieties are in constant development. For example, Masumi uses a new Miyama Nishiki variant called Hitogokoshi, which comes even closer to the brewer’s ideal. In addition, most brewers further increase quality by cleverly putting the best talents of two or three varieties to work in a single brew. Rice that dissolves well is used in the main fermentation mash, and a different variety with higher shinpaku will be used to cultivate the koji mold and concentrated yeast cultures that are the real heart of the sake’s unique flavor profile.

So, in sake as in Japanese society at large, it isn’t the single stand-out performance of a big name star that matters as much as the combined efforts of a host of lesser players, from good rice and clean water, to lowly molds and yeasts.

Words by Keith Norum