Story by Katie Cork

Photos by Dov Friedmann

For most of mankind’s history, flying was strictly for the birds. Only a few visionaries ever thought that human flight was possible. Icarus thought it, but burned his wings trying to prove it. Leonardo da Vinci thought it and designed a helicopter which might have worked, had the internal combustion engine been invented 400 years earlier.

In the 18th century, leaving the ground entered the realm of the possible, as the Montgolfier brothers lifted first a sheep, then a man, over Paris in a crude hot air- (and smoke-) filled balloon. Count von Zeppelin took ballooning to new heights with his airships at the turn of the century, and only three years later in 1903 Orville Wright left the ground—briefly—in the first-heavier-than air flying machine at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina.

Since then, man hasn’t looked back. If war has been the greatest impetus to the development of manned flight, peacetime has seen the huge growth in flying for leisure. There are a surprising number of people in Japan who take to the skies for pleasure and for sport. What makes apparently sane people leave the comfort of terra firma to fly, to glide, to fall, to swoop or to jump out of planes at 12,000 feet? It was to them—and to the skies—to which I turned to find the answer to this question.

Up, Up and Away in My Beautiful Balloon

More than 200 years after the sheep did it, I am about to embark on my first balloon flight, 80 km. north of Tokyo in Watarase, a natural reservoir and the largest expanse of flat land in Japan. My pilot is Sabu Ichiyoshi, the man responsible for bringing hot air ballooning to Japan and in 1976 the first person to float over Mount Fuji.

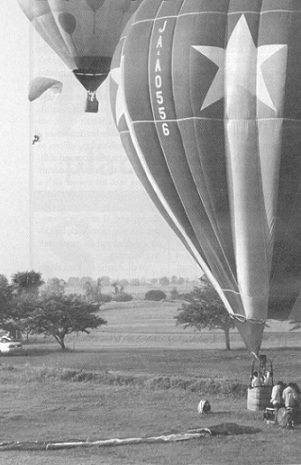

Sabu-san began ballooning in the early 1970s, traveling to Germany to gain his gas and hot-air balloon pilot’s licenses. Returning to Japan complete with hot air balloon in 1974, he co-founded the Japan Balloon Federation which co-ordinates activities from registration of licenses to official competitions. There are now more than 300 registered balloons and 2,000 qualified pilots regularly flying. Today, balloons in Japan are lifted by hot air rather than the more expensive helium or hydrogen.

The best time for ballooning in Japan is early in the morning when the air is calm and thermal-free. We leave Tokyo unsociably early a little before 5, and arrive at Watarase, near the town of Fujioka, around 6 a.m. Already there are about 10 balloons in various stages of expansion, some floating gracefully up into the atmosphere, giant blocks of color against the white-blue sky.

In just 15 minutes the nylon envelope is inflated with hot air. We jump into the basket and climb slowly toward the clouds. At this time of day, the world is wonderfully peaceful—just the sound of distant burners pushing hot air into the envelopes of nearby balloons and songbirds below. We climb to around 1,000 feet and for a while seem to be standing still. Leaning to look over the edge of the basket feels safer than looking from the balcony of a tall building.

The sky is hazy, which slightly restricts the distant view, but below us are fresh, green meadows broken only by the occasional road and waterways that reflect our image as we pass overhead. In this high-tech age ballooning is satisfyingly old-fashioned, though it has come a long way since the first balloon attempts of the 18th century. Attached to the basket are instruments measuring GPS, altitude, wind speed and direction. Winds are key to ballooning—the skilled pilot uses different wind speeds at different altitudes to move in the desired direction. We are treated to a demonstration of Sabu-san’s skill as we descend to the ground and glide over the fields just inches from the earth before ascending once more.

When we land an hour and a half later, we are met by Nobu-san, our “chaser” who has been following our progress in the car by radio. This is surely the most relaxing way to fly. I feel positively serene as we climb from the basket. I can think of no better way to start a Sunday morning.

To become a hot-air balloon pilot in Japan, candidates must speak and read Japanese, and join the Federation. Training consists of 10 flights with an instructor, plus classes and a written examination. Qualified pilots from overseas can fly in Japan if they join the Federation and have their licenses rewritten in Japanese. Balloons cost between ¥3 and ¥4 million and pilots often form syndicates to split the cost and share balloons.

For those who want to experience the freedom of flying in a hot-air balloon just once, the Tokyo Aeronauts Club, run by Sabu-san, offers weekend flights from Watarase. You can bring your own champagne!

Free-for-All

After our balloon flight, we bump into a group of skydivers from the Fujioka Skydiving Club. The club meets every weekend at Watarase, and offers skydive training and tandem flights in which guests are strapped to a qualified instructor. Preparation is a 10-minute talk and video. Guest jumpers must book in advance. The club offers a pick-up service from Fujioka for those arriving by train.

Sayuri Yamazaki, an Equities Researcher from Tokyo, has been skydiving for a year and has already completed about 100 jumps. I want to understand why jumping out of a plane or helicopter from 12,000 feet is so compelling. Why did she start skydiving? “My friend and I wanted to do something unusual,” she explains, “so we did a tandem guest jump here. It was the freest feeling I had ever had and I just had to do it again.” Sayuri-san completed the three-day course that starts with ground training, progresses through tandem sky-dives to accompanied dives with instructors and finally to solo freefall.

As we are talking, a flock of skydivers land nearby, some being guided in by an instructor by radio. While they are mostly young, there is no upper age limit for skydiving—in fact, no restrictions at all apart from a clean bill of health.

The biggest fear for many is the thought of hurtling towards the ground. Skydivers say that the feeling is one of floating rather than falling. Because the plane or helicopter is already moving at “terminal velocity” (around 120 miles per hour), the forward speed simply graduates into downward speed. Jumpers fall at around the same speed, so relative to each other, it feels as if one is flying rather than falling.

Sean Mathis, an international sales manager from San Jose, California, gives a persuasive explanation of the thrill of tandem skydiving. It is, he says, “like going along for the most incredible ride of your life!” For as long as he can remember Sean wanted to fly. “When I was about 5, I started dreaming about flying. One day I was sitting in the car with my father and I told him that I wanted to change my name. He thought it was because I didn’t like the name Sean. I told him it wasn’t that, but that I wanted to change my name to ‘Peter Pan.’ I really thought that if I changed my name to Peter Pan I would be able to fly.”

When Sean was 16, he started flying planes and at 18 he tried hang gliding. A few years later he decided to get his skydiving license. It was everything he had dreamed of. He says, “On Apr. 24, 1991, I finally became Peter Pan!”

In 1999 and living in Japan, Sean joined the Tokyo Skydiving Club whose members jump at Honda Airport in Saitama-ken. The club has about 200 members. If you already have a licence and your own parachute, becoming a member is easy. For non-Japanese people, getting a licence can be difficult, he says, but doing a tandem jump is great. He concludes: “If anyone has ever looked up at the sky, seen a bird gliding on the wind and wondered what it would feel like, definitely try skydiving.”

I’m beginning to think that it might not hurt to try it—one day.

Free as a Bird

Of all the ways to fly, perhaps hang gliding emulates most a bird flight. The sport was brought to Japan from Europe by a bunch of enthusiasts around 20 years ago. No instructors, no insurance and no designated flying areas. From this chaotic and potentially dangerous start, the Japan Hang Gliding Federation (JHF) was born. The JHF works to ensure that gliding in Japan is professional and safe, and has around 24,000 student, pilot and instructor members.

According to Tomoko Kobayashi of the JHF, many members choose to paraglide rather than hang glide. This may have something to do with the equipment. Paragliders have a canopy, harness and helmet that fit into a large rucksack-type bag, weighing around 30 kg. Hang gliders also have to transport and store an aluminium frame.

Hang gliders are aerodynamic in shape, which is what makes them glide. The canopy has ribs in the sail, just like an umbrella, which makes it flexible but solid. Attached to a single center of gravity by a harness made of strong webbing, hang gliders fly with bodies vertical. Legs tuck into a sleeping bag-like pouch that is attached to the harness at the waist. Paragliders have no frames. The canopy is jellyfish-like with air pockets that are inflated by incoming air. Paragliders fly in a supine position, the harness forming a “seat” which makes their running launch look a little undignified.

Naomi Miyamoto, a web designer from Tokyo, has been hang gliding for seven years. Naomi belongs to the Kaicho School in Nishi Fuji, Shizuoka Prefecture, between two and three hours away from Tokyo by car. The Asagiri Mountains near Lake Motsu and Mount Fuji are their launch pad. Naomi, who always wanted to fly, started gliding while

she was studying in Tucson! Arizona.

Her enthusiasm is obvious: “There is nothing like the feeling of freedom you get when hang gliding,” she says enthusiastically. It’s indescribable. It’s my motivation; it keeps me going back to the mountains every weekend.”

Gliders jump off mountains to launch themselves into the air and can fly hundreds of miles, staying up for hours using hot air thermals that rise as high as the cloud base (around 2,000-3,000 meters above sea level in Japan). Gliders usually have a designated finish zone that they must aim for; the sport depends upon agreeable landowners who are happy for people to land in their fields. Weather is an important factor:

January to May are the best months in Japan for gliding, and the rainy season keeps pilots on the ground.

Serious hang gliders and paragliders can expect to train for up to two years before becoming a pilot. On top of training costs, pilots must purchase their own canopy, harness, helmet and radio, which can be as much as ¥400,000. With proper instruction, hang gliding is very safe. The most dangerous times are take-off and landing. Naomi has only had one serious accident, waking up in the hospital with a broken nose and cracked cheekbone after her wing caught on the branch of a tree during a landing. Three weeks later she was back in the air.

For people interested in trying hang gliding, there are schools that offer tandem flights. One of these is the Opa Kite School in Ibaraki Prefecture. Toshiyuki Katsura, an experienced English-speaking instructor, has taken men, women and children of all ages up into the air. Expect to go up perhaps two or three times in a day, for as long as 10 minutes a time, depending on air conditions.

Tokyo Skies

If all this seems a little too energetic and you want something a little closer to home, the most satisfying way to see Tokyo from the air is by helicopter. Ace Helicopters, based at Tokyo Heliport, offer a bird’s-eye view of the sprawling metropolis. The helicopter seats up to four passengers and the flight lasts 15 minutes. Plenty of time to see Tokyo from a different angle and a great way to show guests the city. In addition to offering scenic tours over Tokyo, Ace Helicopters is the number one agricultural sprayer in Japan, has transported small shrines to the top of mountains, and connected electricity cables to mountain pylons.

In Okinawa they work with the U.S. Marine Corps to reforest artillery training areas destroyed by shells—without such a program, the denuded soil would be washed out to sea where it could damage the delicate coral ecosystem. They also conduct geophysical surveys that measure volcanic activity and analyse the likelihood of earthquakes. During this year’s ski season, Ace Helicopters took more than 2,000 people heli-skiing in Nagano Prefecture. They are available for private charter (recent clients include Ichiro and Tiger Woods).

Our pilot, Suzuki-san, has 3,800 hours in the air, so I am not worried as the blades spin faster and the helicopter wobbles a little as it leaves the ground. Heading out over the bay, Rainbow Bridge is straight in front of us. We turn inland towards Tokyo Tower. The scenic tours fly within the Yamanote Line and the bay area of Tokyo, and you can specify particular areas that you would like to fly over. As we circle Tokyo Tower to allow our photographer to get a good shot, it feels like something out of a Hollywood movie, circling the bad guys who have taken the control tower.

From 1,000 feet, Tokyo looks completely different. Gone are the overhead cables and the architectural mismatch of high-rise office building next to mom-and-pop store next to 50-year-old houses. The city is transformed into neat blocks of orderly buildings and roads, interspersed with large patches of trees and parkland. This is probably the only way you will see the Imperial Palace and the beautiful Imperial guesthouse.

If a flight over Tokyo is not enough and if you have ¥600,000 to spare, you might want to consider a helicopter ride round Mount Fuji around an hour from Tokyo. This would surely be a once-in-a-lifetime flight over Japan’s most famous and arguably most beautiful landmark.

Give it a Go!

For most of us, flying is purely a means of getting from A to B. You probably see air travel in terms of long check-ins, airline food and air mileage. But the people I met find excitement and adventure, an extraordinary sense of freedom. They see flying in terms of an earlier age of magic and romance. I can now understand why sky sports enthusiasts become hooked so quickly and take to the air at every available opportunity. I just might join them.