Story and Photos by David Tharp

TENKAWA, NARA – Tenkawa Shrine is a name that strikes tremors of mystic excitement in the hearts of new age enthusiasts all over Japan. It is alleged to be a “psychic power spot” for spiritual inspiration and healing.

Many people, including the rich and famous, make pilgrimages to Tenkawa even though it is located in an isolated village buried in the misty mountains of southern Nara Prefecture. It is compared to “sacred places” such as Mt. Shasta in the U.S. and the holy American Indian sites in New Mexico. Psychics say the ethereal “vibrations” emanating from the shrine are the most exciting in Japan.

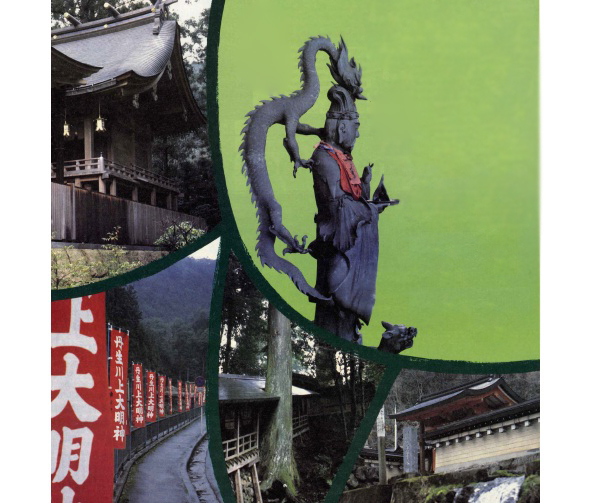

The official name of the jinja (shrine) is Tenkawa Daibenzaiten-Sha. It is dedicated to Benzaiten, the goddess of creativity, wisdom and abundance, and it was founded in the late 7th century during the reign of the Emperor Temmu.

The chief guji (Shinto priest) is Mikinosuke Kakisaka, an eccentric, jolly man who sits around the jinja stove with visitors on a cold winter night, serving them sacred sake and telling stories of numerous spiritual healings and inexplicable events that have occurred there.

Kakisaka claims no cultural exclusivity for Shinto, he says that all religions are pathways up the mountain to the same God, but he asserts there is something about his shrine that is very mysterious indeed.

A number of psychic healers seem to agree. Foreigners and Japanese who hold workshops in Tenkawa village claim to have made dramatic breakthroughs with many people suffering from deep psychological and spiritual pain, aided by the atmospherics of Tenkawa.

So, it was as if I had been handed a live circuit cord of psychic electricity when I was asked to hold a healing workshop at Tenkawa for a group of doctors, nurses, professors, teachers, religious experts and social workers from Tokyo and Osaka.

I conducted many healing workshops in the U.S., Canada, Central America, the Philippines and Japan for suicide prevention groups, hospices, mental health associations, hospitals, churches, synagogues and parents of murdered children, but this would be the first time at a Shinto shrine. The experience was to be the basis for a book that will be published later this year in Japanese about healing and Tenkawa jinja.

Usually, visitors hold workshops in the meeting hall adjacent to the shrine, but I decided to try something that no one had ever done before in-Japan. I asked to use the shinden, the inner sanctuary of the shrine for the final, dramatic healing ritual of my workshop.

It was an unprecedented request that evoked a great deal of debate among the shrine’s priests. I explained that I wanted to confront my group directly with the metaphysical power of the shrine’s kami (spirit) to intensify the healing impact of the workshop.

I felt the shinden experience would be a compelling, cleansing catharsis for everyone, a once-in-a-life-time chance to start over or get an inspiration to try something new with their lives. What I had in mind were the words of Joseph Campbell, the great American cultural anthropologist, who said, “To have a sacred place is an absolute necessity for anybody today.

“This is a place where you can simply experience and bring forth what you are and what you might be. This is the place of creative incubation. At first you may find that nothing happens there. But if you have a sacred place and use it, something eventually will happen.”

I was determined to use Tenkawa for exactly that purpose and ask the shrine goddess to assist in the healing and creative incubation process. The mystic vibrations seemed just right for this purpose. The shrine priests decided to accept my request to use the shinden after a lot of debate. It was going to be a first for all of us. I thanked them and Benzaiten for their support.

Deep in the mountains

Tenkawa is not on regular tourist routes. The visitor must take a Kintetsu Line train from Osaka or Kyoto and, after several changes, alight at Shimoichiguchi, the nearest station to Tenkawa village. Only two buses a day leave Shimoichiguchi to Tenkawa; one in the morning and the other in the afternoon. The bus drops off people at the bridge that crosses to the village. It takes about 15 minutes to walk from there to the shrine and the nearby minshuku, family inns.

I got a cab from Shimoichiguchi with three interesting people: the director of Japan’s Holistic Health Association, a famous Shinto expert and a well-known cultural anthropologist who specializes in Southeast Asian exorcism practices.

These three gentlemen were also there to take my workshop, and would later compare notes about the impact of the healing rituals on the group for the book. The Shinto expert was astonished that I received permission to use the shrine’s shinden. It was totally unprecedented for a foreigner to get this kind of access, he said.

The road to Tenkawa winds through heavily forested mountains. At times the trees form shady tunnels over the roads, similar to places in southern England, France and parts of South Korea.

Many thatched-roof farm houses line the road. The rice fields here have been cultivated for at least 2,000 years. The taxi driver spoke of many visitors coming from all over Japan to visit Tenkawa.

A number of writers, musicians, actors, religious people and just ordinary folk make trips here to seek the intervention and inspiration of the shrine’s goddess, Benzaiten.

The taxi driver told colorful stories about people who have visited the Tenkawa. Several visitors claimed to have seen a whole squadron of UFOs circle the shrine one night. We laughed but the driver insisted inexplicable things do happen around Tenkawa. For example, “strange” bright lights have been spotted often on the mountain behind the shrine late at night, he said.

The plot thickens

Tenkawa is a small village surrounded by mountains. Since ancient times, the villagers lived as foresters making lumber and wood products. Tenkawa Jinja stands in the center of the village, enclosed by tall cypress trees. There are just a few, small family-run shops in the village. Visitors stay in homes that villagers have converted into comfortable minshuku.

After arrival, I went to the shrine to offer respects to the kami, Benzaiten. One of the shrine’s guji invited me to make an offering of cut cypress tree branches tied with sacred paper in front of the shrine’s traditional mirror and inner sanctum which contains the kami’s image.

The scene was set, the actors ready and the goddess had been apprised of our intentions. The jinja weaves an extraordinary mood. It has an air of serenity coupled with a mood of expectancy, a sense that something is going to happen or is already happening here.

The 30 participants in the workshop, men and women mainly from the Osaka area, assembled in the sanshuden, the meeting hall next to the shrine proper.

I led them through some self-introductions, preliminary exercises and then we finally dove into the healing issues. Tears flowed, pain was intense but, more importantly, hearts started to open. Some people struggled with memories of parental abuse; others with lost innocence and still others with unforgettable tragedies.

Little by little, the group started to come to terms with and rework their experience with life—love, career, dreams and the ethereal. We become poets and rewriters of life’s script. Through the various inner directed exercises the participants looked at their doubts and despair, but also they found ways into the light and a grasp on hope, even if it was just a small fingernail hold.

Then the time came for the final part of the drama. I assisted each person to plan how they would deal with their healing ritual in front of the Benzaiten. Each person readied him or herself to release the past and embrace the new and unknown.

We moved from the sanshuden to the shinden. I played some special, evocative music and we started the healing rituals. As each person came to the front of the kami, something far out of the ordinary occurred. Each person appeared to go through a major transformation as they chanted, prayed, danced, sang or acted out the single burning issue of their life and offered it to Benzaiten for healing. Facial expressions changed and spirits soared as each person completed their ritual and moved to the sidelines for the next person to “perform.” Shrine visitors who happened to drop by to make an offering stood in awe as people danced by them in a blissed-out state.

We must have been under the influence of Benzaiten and her angelic friends because nobody else seemed to be in control; certainly not me. Finally, everyone finished their personal healing process, and I led the group in a special dance dedicated to Benzaiten to thank her for her assistance.

I felt extremely high and humble about being the first foreigner to conduct a healing process like this in a Shinto shrine. Later, it was hard to recount intellectually what had actually happened. There were a lot of happy, smiling people who came up to thank me for what I had done.

But, strangely, I didn’t think I was really responsible for the most important part of what happened that day. I felt I had been just a bystander.

I was invited back to do another healing workshop at Tenkawa in mid-July. This time the chief guji joined the healing ritual, adding his own prayers to the process.

Later, he invited me to a special midnight fire ceremony in the shinden to give sacred sake and other offerings to the shrine kami. As he chanted, I could almost feel the presence of Benzaiten—but I didn’t see any UFOs.

I’m convinced miracles can happen in people’s lives. I have seen it happen many times. Perhaps we need to do as Joseph Campbell advises and find a sacred place like Tenkawa to incubate our miracles. Who knows? Perhaps Benzaiten does.