Two gardens

Here is a way to wile away a lazy afternoon any season of the year. First a light lunch of soba noodles at a famous old Tokyo noodle shop, then a stroll through two adjacent parks, one the landscaped, manicured grounds of the residence of a prince, with lawns like a Cambridge college. The other a national nature conservancy, a 50-acre piece of land that has been left just as it was before there was a city here, the last existing natural path of the Musashi Plain, with great mossy trees 500 years old —there’s nothing like it in any city anywhere in the world.

That it could exist in hard-charging Tokyo, a city normally intent on excavation, is nothing short of miraculous.

Exit Meguro Station onto Meguro-Dori and turn left. Eighty meters down the street you will see a sign:

Shizenkyoiken -> 470 m

Teien Art Museum -> 420 m

which h where you are going. On the next corner, you will see another sign announcing the presence of a Chinese restaurant called Han, which however is not where you are going.

Turn left here and go 50 meters to a plain, worn wooden house on the left hand side of the street. This is the soba shop called Issan, celebrated for its handmade noodles and its utter lack of pretention, which is where I suggest lunch. (Note, though, that Issan is not open Wednesdays.)

Issan

Divest yourself of your shoes in the little entranceway. A waitress in kerchief and jeans will show you to one of the low tables in one of the tatami-matted rooms, then she will kneel to solicit your order, which might be, for example:

Seiro (¥550)—an order of plain noodles, or

Nishoku (¥750)—two different kinds of plain noodles, or

Sanshoku (¥1,200) — three different kinds of plain noodles, or (if you are in an extravagant mood)

Yuzukiri (¥900) — soba noodles flavored with the juice of the yuzu, a delicate Japanese citrus fruit.

A ¥200 order of pickles would add crunch.

This is the way a soba connoisseur orders.

Take a look at the kitchen out back before you leave. There is a huge pot of boiling water, a board on which to cut the noodles, racks for the bowls and a single jolly chef. Couldn’t be simpler. The little cabinet in the entranceway displays things customers satiated to forgetfulness have left behind: a key chain, a tortoise shell shoe horn, an earring, a tiny pine cone. They will probably be here in this cabinet when you come back.

Teien Art Museum

It costs ¥100 to enter the garden with an extra charge, amount depending on what is currently on exhibit, to enter the museum itself. The museum used to be the private house of Prince Asaka, the eighth son of Prince Kuni. He married Princess Nobuko, the eighth daughter of Emperor Meiji. The Prince studied in Paris, where he became enamored of Art Deco and he commissioned Henri Rapin, a French architect in great vogue at the time, to design this house for him and his bride.

The house was completed in 1933 and is far and away Tokyo’s best example of the genre, with wonderful doors and lighting fixtures and banks of heroic Lalique glass.

Unfortunately, the house was turned into a museum with a heavy hand and this, together with the fact that most of the exhibitions held here are unaccountably second-rate, drains a visit to the house of much of its interest. The house should be completely open to the public, its doors and windows thrown open to the garden, period furniture and bibelots put on display, concerts of Stravinsky and Satie held every weekend in the Great Hall and characterful restaurants installed in each of the house’s two dining halls. Perhaps someday…

But the Prince’s garden is very pleasant, although it is closed on the second and fourth Wednesday of the month, unless one of those days is a National Holiday, in which case it will be closed the next day — except if there is a full moon (just kidding).

Here we have a secluded teahouse, a pond with lolling carp, a rolling landscape with groves of trees, comfortable wooden benches under the trees and tables and chairs scattered about — singular rarity for Tokyo -— on the grass. Families come to spread a picnic and watch their children frolic in disbelief that such a place could exist except in fairy tales.

Prince Asaka’s garden is for its fans Tokyo’s most congenial public park, for indulging in dolce far niente, for putting one’s face up to the sun, for sitting and reading a slow-moving novel or for catching up on one’s more frivolous correspondence. Too many of Tokyo’s parks are either so crowded you cannot linger or so restrictive you can only shuffle along a narrow, roped-off path, so the good Prince had bestowed on us a benefaction.

But do not linger here past three o’clock or you will not be permitted to enter Shizenkyoikuen, the National Science Museum’s Institute for Nature Study, which is right next door (Linger all you like on Mondays, though, as on this day Shizenkyoikuen is closed.)

Shizenkyoikuen

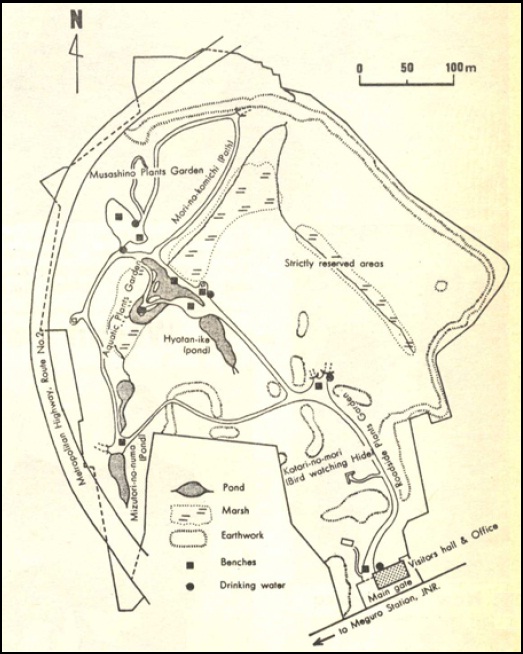

Depending on your mood, this will probably be the high point of the afternoon. It costs ¥170 to enter, which buys you a ribbon to pin on. Because there are only 300 ribbons and because you have to return your ribbon when you leave, the number of people allowed in at any one time is limited, praise be. This is a serious, Japanese-type place and sometimes there are lectures. There may be a notice: “Today’s research theme is spiders.”

Inside, with so much green-cry, the air is pure. Along the walk in, plants have been cultivated for delectation in their variety: Hitorishizuka (“Alone and quiet”), Futarishizuka (“Two quiet together”), Yaburegasa (“Crumpled hat”), Jamohige (“Snake’s moustache”). Many of these species could not be allowed in a cultivated garden, being mere, but marvelous, weeds.

There are about 8,000 trees in here, of all sorts, even palm trees. Every eight years a select band of students of horticulture from Tokyo’s universities conduct a tree census, registering the height and girth of every tree in a series of large notebooks, (Unbridled nature is an excellent concept, a fine subject for study.)

Photographers in safari dress come with tripods and huge lenses to photograph the curve of pampas grass against the sky. The only sound is the crunch of gravel on the path and the call of birds.

Here raw nature seems somnolent, not tooth and nail. Leaves fall thick on the ground. Parasitic vines entwine. Mushrooms grow on the sign posts. In a murky pond, turtles lounge on a log. A wooden bridge winds through the lily pads and a huge carp, like a drowsy submarine, just lives here.

One section is roped off because a tree is about to fall. When it does, it will be left as it falls. A huge 300-year-old pine, of a species called Kuramatsu which has no branches, snakes into the sky. Old plants wither, new ones green, but a stand of Konara, good wood for charcoal, grows so thick that young trees of its species can get no sun, and so in a hundred years the pines, whose young require less sun, will take over.

As we leave, we resolve to come back the next season, when it will all be different.